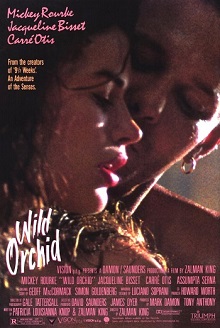

Emily (played by blank-faced model Carrie Otis) is a lawyer who can speak French, Spanish, Portuguese, Chinese, and Italian but who has never spoken the language of love. A high-powered New York firm hires her away from her former employer in Chicago on the requirement that she immediately head down to Rio de Janeiro. Claudia Dennis (Jacqueline Bisset) is trying to close the deal on buying a luxury hotel and she needs a lawyer now!

Emily (played by blank-faced model Carrie Otis) is a lawyer who can speak French, Spanish, Portuguese, Chinese, and Italian but who has never spoken the language of love. A high-powered New York firm hires her away from her former employer in Chicago on the requirement that she immediately head down to Rio de Janeiro. Claudia Dennis (Jacqueline Bisset) is trying to close the deal on buying a luxury hotel and she needs a lawyer now!

Claudia, however, has plans for Emily that go beyond real estate. As soon as Emily arrives, Claudia arranges for her to go on a date with the wealthy and mysterious James Wheeler (Mikey Rourke). Wheeler is single but he’s so far refused all of Claudia’s advances. She wants to know if he’s adverse to all women or just her. Wheeler is very taken with Emily but he’s been hurt so many times in the past that he can’t stand to be touched. Instead, he gets his thrills by being a voyeur.

It leads to a trip through Rio, where everyone but Emily is comfortable with their sexuality. When Wheeler isn’t encouraging her to watch a married couple have sex in the back seat of a limo, Claudia is encouraging Emily to disguise herself as a man and enjoy the nonstop carnival of life in Rio. There’s a lot of business double-dealing, many shots of Mickey Rourke riding on his motorcycle, and a final sex scene between Rourke and Otis that is one of the most rumored about in history. For all of the scenes of Wheeler explaining his philosophy of life, Wild Orchid doesn’t add up too much, though it certainly tries to.

Wild Orchid was a mainstay on late night Cinemax through most of the 90s. This was Carrie Otis’s first film and to say that she gives a bad performance does a disservice to hard-working bad actors everywhere. There’s bad and then there’s Carrie Otis in Wild Orchid bad. She walks through the film with the same blank expression her face, playing a genius who can speak several languages but often seeming as if she’s struggling to handle speaking in just one language. She looks good, though, and all the movie really requires her to do is to look awkward while Rourke and Bisset chew up the scenery.

On the one hand, Wild Orchid is the type of bad movie that squanders the talents of actors like Mickey Rourke, Jacqueline Bisset, and Bruce Greenwod (who has a small role as a sleazy lawyer) but, on the other hand, it’s a Zalman King film so it may be insanely pretentious but it’s also rarely boring. Visually, King goes all out to portray Rio as being the world’s ultimate erotic city and the dialogue tries so hard to be profound that you’ll have to listen twice just to make sure you heard it correctly. My favorite line? “We all have to lose ourselves sometimes to find ourselves, don’t you think?” Mickey Rourke says that and he delivers it as only he could.

Wild Orchid may have been a box office bust but it was popular on cable and on the rental market, largely because of that final scene between Rourke and Otis. Mikey Rourke later married Carrie Otis. Neither returned for Wild Orchid II: Two Shades of Blue.