(For those following at home, Lisa is attempting to clean out her DVR by watching and reviewing 38 films by the end of this Friday. Will she make it? Keep following the site to find out!)

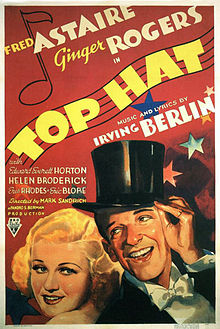

The 1935 film Top Hat is a film that, much like An American In Paris, is pure joy.

Top Hat features Fred Astaire as Jerry Travers, a famous dancer who has come to London to star in a show that’s being produced by his friend, Horace Harwick (Edward Everett Horton). (Oddly enough, Gene Kelly also played a character named Jerry in An American In Paris.) Jerry may be sophisticated and refined but he’s still enough of an American that, upon leaving a snooty British club that insists on total silence, he still breaks up the tedium with some impromptu tap moves.

Back at his hotel, Jerry is practicing a tap routine and makes such a racket that he ends up waking up the guest staying in the room below him, Dale Tremont (Ginger Rogers). When Dale goes upstairs to complain, Jerry immediately falls in love with her. Soon, he is pursuing her all over London, trying to win her heart. Eventually, he even follows her to Venice.

And Dale is definitely attracted to Jerry. Whenever they get near each other, they start dancing. (Needless to say, whether they’re dancing or talking or merely looking at each other from across the room, Astaire and Rogers have wonderful chemistry.) However, Dale thinks that Jerry is actually Horace. And Horace happens to be married to her friend, Madge (Helen Broderick.) Convinced that Jerry is pursuing an adulterous affair with her, the indignant Dale makes plans to marry the Italian fashion designer, Alberto Beddini (Erik Rhodes).

The plot is typical screwball comedy stuff and the fact that you don’t even end up getting annoyed with all the misunderstandings is a testament to the abilities of Astaire, Rogers, and their wonderful supporting cast. Even if not for the dancing, Top Hat would be a success because of the chemistry between the actors and film’s mix of sophistication with just pure silly fun. I imagine that for audiences dealing with the daily realities of the Great Depression, Top Hat offered a wonderful escape. And you know what? It still provides a wonderful escape for today, as well.

(Wouldn’t it be nice if we could just dance this presidential election away?)

And then, of course, there’s the dancing. That really is the main reason that we’re here, right? Check out a few scenes. They’ll make you happy.

(Incidentally, I’m a bit disappointed that YouTube does not feature more from Top Hat.)

Top Hat was nominated for best picture, though the award itself went to Mutiny On The Bounty, a film that did not feature quite as much dancing.