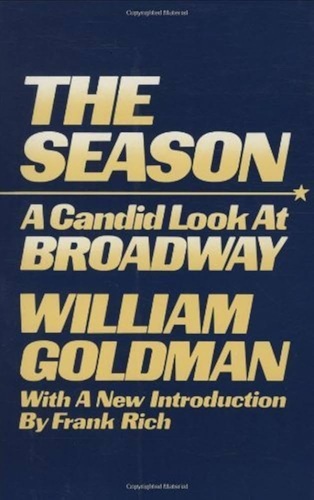

With the Tony Awards scheduled to be held and televised on Sunday, this weekend might be a good time to read William Goldman’s The Season.

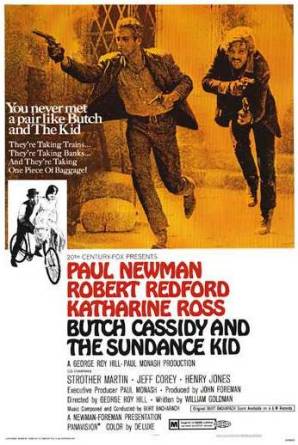

First published in 1969, The Season was William Goldman’s very opinionated and very snarky look at the 1967-1968 Broadway season. Best known as a screenwriter, Goldman took the money that he made from selling the script for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and spent a year going to Broadway show after Broadway show. Many shows, he sat through multiple times. The book features his thoughts on not just the productions but also the culture around Broadway. Apparently, when the book was published, it was considered controversial because Goldman suggested that most Broadway critics played favorites and didn’t honestly write about the shows that they reviewed. Goldman suggested that some performers were viewed as being untouchable while other worthy actors were ignored because they weren’t a part of the clique. Today, that seems like common sense. One need only look at a site like Rotten Tomatoes to see how pervasive groupthink is amongst film critics and also how carefully most reviews are written to ensure that no one loses access to the next big studio event. In 1969, however, people were apparently a bit more naive about that sort of thing.

It’s an interesting book, especially if you’re a theater nerd like me. That said, it’s also a bit of an annoying book. There’s a smugness to Goldman’s tone, one that is actually present in all of Goldman’s books and essays and yes, aspiring screenwriters, that includes Adventures In The Screen Trade. He clearly believed himself to be the smartest guy in the room and he wasn’t going to let you forget it. It makes for a somewhat odd reading experience. On the one hand, Goldman’s style is lively. Goldman holds your interest. On the other hand, there will be times when you’ll want to throw a book across the room. When he hears two women talking about their confusion as to why they didn’t enjoy a show as much as they had hoped, Goldman describes walking up to them and offering to tell them. It comes across as being very condescending.

That said, Goldman makes up for it in the chapters in which he explores some of the more troubled productions of the season. His barbed dismissals of some of Broadway’s most popular performers still packs a punch and it remains relevant today as there are, to put it mildly, more than a few acclaimed performers who have been coasting on their reputations and their fandoms for more than a decade. Goldman passed away in 2018. One can only imagine what he would think of today’s celebrity-worshipping culture.

Finally, The Season does feature one beautiful chapter and it should be read by anyone who appreciates the character actors who carry movies and plays while the stars get all the credit. Goldman’s look at play called The Trial of Lee Harvey Oswald features a powerful profile of actor Peter Masterson. Goldman writes about a play that closed after 7 nights and which was not critically acclaimed but he turns the chapter into a celebration of truly good acting. It’s the chapter that makes the rest of the book worth the trouble.