“Knowledge without action is but a hollow echo.” — Heismay

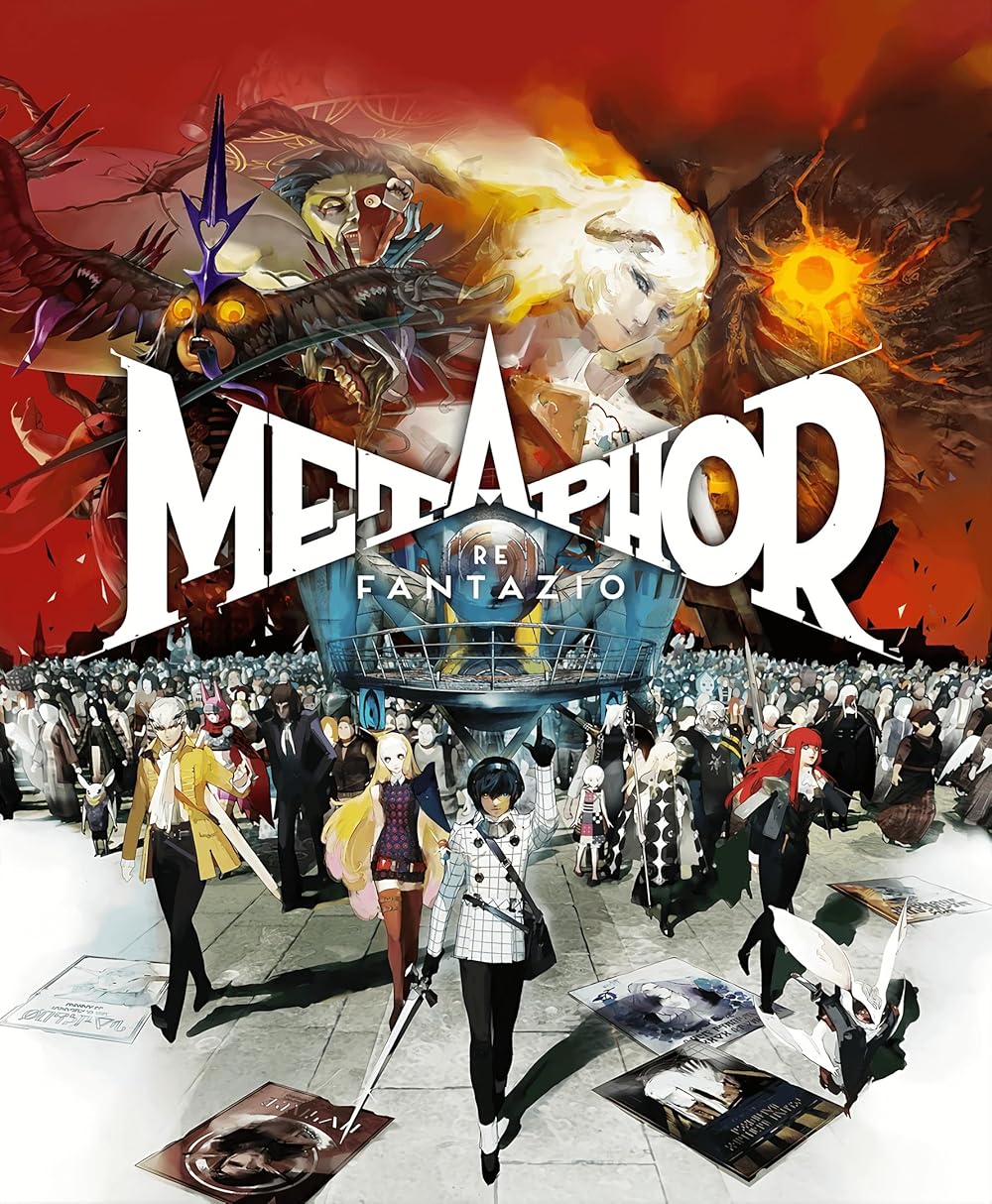

Metaphor: ReFantazio delivers a fresh fantasy spin on Atlus’s signature JRPG formula, blending turn-based combat with real-time field encounters that keep battles dynamic and strategic, all in service of a narrative that probes deep into societal divides. The game’s Archetype system lets you mix and match job classes across your party, offering deep customization through skill inheritance and squad synthesis for creative builds that shine in tough boss fights, mirroring the story’s emphasis on unity through diversity. While the overarching tale of tribal tensions and royal intrigue captivates from the start, it occasionally leans into familiar Atlus tropes like social bonding and time-sensitive quests that can feel repetitive over its lengthy runtime, though these mechanics cleverly reinforce the plot’s ticking-clock urgency.

Traversal feels epic on your flying sword mount, zipping through vibrant medieval-inspired hubs packed with side requests, from monster hunts to delivery gigs that boost your follower ranks and unlock new abilities, often tying back to the narrative’s exploration of prejudice and alliance-building. Visually, the stylized UI, animated portraits, and lush world design pop with that classic Atlus flair, making every menu and cutscene a treat, with the game making especially striking use of character artist Shigenori Soejima’s artwork to give both the interface and the cast a distinctive, cohesive look. Soejima, known for his work on the Persona series, brings his signature style here—sharp lines, expressive faces, and vibrant color palettes that make every character portrait feel alive and every UI element intuitive yet stylish, visually underscoring the diverse tribes and their clashing ideologies. The character designs stand out particularly in combat, where Archetype shifts trigger flashy animations that highlight Soejima’s attention to detail, from flowing capes on knights to ethereal glows on mages, ensuring the visuals never feel generic despite the fantasy setting that grounds heavy themes.

The soundtrack nails epic orchestral swells during climaxes, paired with solid voice work that brings the diverse cast to life, even if not every dialogue line gets full voicing, amplifying the emotional weight of key story revelations. Composed by the talented team including Shoji Meguro’s influences, the music shifts seamlessly from tense dungeon crawls with pulsing synths to triumphant fanfares during story beats, enhancing the world’s medieval-fantasy vibe without overpowering the action, and perfectly suiting monologues on fear and ignorance. Voice acting, mostly in Japanese with English subtitles as an option, adds authenticity, though the selective dubbing in key scenes keeps things efficient without sacrificing impact during pivotal tribe confrontations.

Diving deeper into the narrative, Metaphor: ReFantazio crafts a world called Euchronia, where the protagonist—a member of the persecuted Elda Tribe—embarks on a quest to save the cursed prince and compete in a grand tournament to claim the throne, all amid rising prejudice fueled by mysterious monsters born from collective human anxieties like doubt and rage. The central theme of ignorance as the root of fear resonates thoughtfully throughout, explored through bonds with followers from various tribes—each with backstories rooted in discrimination, from the scholarly yet shunned eugief tribe to the ethereal Nidia—tying personal growth to larger societal critiques on tribalism and unity. These relationships aren’t just filler; they directly influence your combat prowess by unlocking new Archetypes and synthesis options, making social links feel mechanically integrated rather than tacked-on, while reinforcing the plot’s message that strength emerges from understanding others. Yet, the script sometimes prioritizes exposition over subtlety, with dialogue that explains themes a tad too on-the-nose, especially in early acts before the plot’s twists—like betrayals in the royal election—ramp up the stakes and deliver more nuanced emotional layers. The narrative culminates in a tournament arc where your speeches sway public opinion, blending political intrigue with fantasy in a way that feels timely, critiquing how fear-mongers exploit divisions without ever feeling preachy.

The game’s themes extend far beyond surface-level fantasy politics, weaving in profound ideas about human cognition and societal ills, best encapsulated by the line “O worthy heart, who tempers anxiety into strength”—a recurring invocation when awakening Archetypes that perfectly distills how the story transforms personal and collective fears into heroic potential. Ignorance isn’t just a buzzword; it’s literalized through the mechanics of human cognition, where unchecked emotions manifest as those Bosch-inspired monsters—grotesque hybrids symbolizing sloth, lust, or despair—challenging players to confront not external evils, but the shadows within collective psyches. This ties into broader explorations of tribalism, where each playable tribe represents marginalized groups: the immortal Elda as eternal wanderers mistrusted for their longevity, the brutish Nidia dismissed as savages, paralleling real-world racism and xenophobia. The royal election mechanic forces you to campaign like a politician, balancing Follower ranks (public support) with bond-building, highlighting how leaders must combat misinformation and rally diverse factions—echoing modern populism without direct allegory, as echoed in More’s constant reminder: “Time marches on, and the age of a new king draws nearer.” Ideas of inherited trauma surface too, as the protagonist grapples with his tribe’s cursed history, questioning if prejudice is a cycle broken only by empathy and action, reinforced by optional lore dumps from informants that unpack Euchronia’s lore of ancient calamities born from unchecked fears.

Later arcs delve into justice versus vengeance, as revelations about the prince and antagonists reveal layers of manipulated ignorance, asking whether punishing the fearful perpetuates division or if education through example prevails. Themes of escapism critique fantasy itself: characters cling to idealized “Royal” saviors, mirroring how societies project hopes onto myths, only for the story to dismantle that by humanizing leaders as flawed products of their biases. Multiple endings—ranging from unified reigns to fractured chaos—hinge on your thematic investments, like prioritizing certain bonds over others, ensuring the ideas stick through mechanical consequence. It’s a mature evolution from Persona‘s teen angst, grounding abstract concepts in tangible choices that provoke reflection on complicity in systemic hate, with Strohl’s encouragement “I really do believe you have the power to change fate itself” underscoring the faith in individual agency amid societal rot.

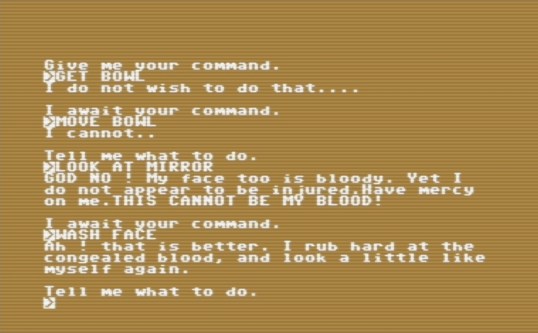

Combat evolves the Press Turn system from Shin Megami Tensei, where exploiting enemy weaknesses grants extra turns, but now with Archetype swaps mid-battle for on-the-fly adaptation—summoning a tank to soak hits or a healer to recover without ending your chain—echoing the story’s adaptive heroism. Squad battles add a layer of real-time command over AI allies during field scraps, bridging the gap between exploration and turn-based depth seamlessly, much like how narrative bonds bridge tribal gaps. Dungeons vary from linear boss rushes to sprawling labyrinths with environmental puzzles, like using wind magic to clear miasma or mounting those monsters for platforming sections, keeping pacing fresh across 80-100 hours and often themed around the anxieties they represent—many of which evoke the nightmarish, hybrid figures from Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, with their grotesque amalgamations of human limbs, animal parts, and surreal machinery perfectly capturing the game’s theme of manifested inner turmoil. Post-game content expands this further with New Game+ carrying over levels and a challenging high-level superboss gauntlet that tests your most optimized builds, inviting replays to uncover alternate endings tied to bond choices.

On the flip side, character arcs stay mostly heroic without much grit or internal conflict, which softens the emotional punch compared to edgier Atlus entries like Persona 5‘s rebellious heists, potentially muting the themes’ bite for some players, and the “days till” deadlines force constant planning that might frustrate casual explorers. Time management becomes a core loop: follow the critical path for story progress, but stray for bonds and requests at the risk of missing deadlines, creating tension that’s smart but stressful for completionists, directly mirroring the narrative’s pressure to confront ignorance swiftly. Some side activities, like the casino minigame or follower requests, offer great rewards but grindy repetition, and while the map system improves navigation with waypoints, backtracking in identical dungeon rooms can sap momentum during marathon sessions delving into lore-heavy side stories.

Accessibility options abound, from adjustable battle speed to auto-battle for farming, making it welcoming for series newcomers wary of steep JRPG curves while they absorb the dense thematic content. Compared to Persona 3 Reload, Metaphor sheds the school-life sim for pure high fantasy, trading calendar dating for royal election drama centered on prejudice, yet retains that addictive “just one more day” hook through its polished systems and unfolding revelations.

Exploration shines in hubs like Grand Trad, a bustling port city alive with merchants, street performers, and cryptic informant conversations that reveal lore tidbits on Euchronia’s fractured history. The monster system lets you befriend (or hunt) foes for your compendium, inheriting skills like in SMT, but with a bond mechanic that speeds recruitment via gifts or dialogue choices—perfect for building that ultimate party and paralleling human alliances, especially when those Bosch-like beasts start feeling less monstrous through repeated encounters. Synthesis combines Archetypes for hybrid classes, like a ninja-healer churning out status cures while stealth-attacking, rewarding experimentation without locking you into dead ends, much like the story’s flexible path to overcoming bias.

Thematically, Metaphor: ReFantazio tackles prejudice head-on through its tribal dynamics and election mechanics, where swaying public opinion via speeches and deeds mirrors real-world politics in a fantastical lens, with each tribe embodying facets of societal “others”—the immortal Elda as eternal outsiders, the brutish as feared brutes—challenging players to dismantle stereotypes. It’s bolder than Persona’s high school metaphors, grounding fantasy in social commentary without preaching, as the protagonist’s journey from outcast to candidate forces reflection on inherited fears passed down generations. Multiple endings based on follower bonds and tournament outcomes add replay value, rewarding deep investment in the themes, while bosses escalate brilliantly, from multi-phase behemoths requiring Archetype juggling to “Clemar” trials testing pure strategy, often with unique gimmicks like reversing Press Turns that symbolize narrative reversals.

For Atlus fans, this feels like the studio firing on all cylinders post-Persona 5 Royal, refining mechanics while daring a new IP unburdened by franchise baggage, with a narrative that stands as one of their most cohesive thematic statements. Newcomers get a guided onboarding with tutorials that don’t overstay, easing into complexity naturally alongside the story’s gradual world-building. Drawbacks like sparse enemy variety in late-game fields and occasional UI clutter during synthesis menus hold it back from perfection, but they’re minor amid the highs of its thoughtful storytelling.

Ultimately, Metaphor: ReFantazio stands tall as an accessible gateway for JRPG newcomers and a loving evolution for fans, balancing highs in gameplay depth with minor stumbles in narrative subtlety, all elevated by its poignant exploration of ignorance and unity. Clocking over 110 hours on a full clear, it earns its GOTY buzz through sheer ambition and polish, proving Atlus can reinvent without losing its soul. If you’re craving a meaty RPG with style, strategy, and a story that lingers on real-world echoes, this one’s a no-brainer—just pace yourself through those deadlines.