I just finished watching the 1982 best picture winner Gandhi on TCM. This is going to be a tough movie to review.

Why?

Well, first off, there’s the subject matter. Gandhi is an epic biopic of Mohandas Gandhi (played, very well, by Ben Kingsley). It starts with Gandhi as a 23 year-old attorney in South Africa who, after getting tossed out of a first class train compartment because of the color of his skin, leads a non-violent protest for the rights of all Indians in South Africa. He gets arrested several times and, at one point, is threatened by Daniel Day-Lewis, making his screen debut as a young racist. However, eventually, Gandhi’s protest draws international attention and pressure. South Africa finally changes the law to give Indians a few rights.

Gandhi then returns to his native India, where he leads a similar campaign of non-violence in support of the fight for India’s independence from the British Empire. For every violent act on the part of the British, Gandhi responds with humility and nonviolence. After World War II, India gains its independence and Gandhi becomes the leader of the nation. When India threatens to collapse as a result of violence between Hindus and Muslims, Gandhi fasts and announces that he will allow himself to starve to death unless the violence ends. Gandhi brings peace to his country and is admired the world over. And then, like almost all great leaders, he’s assassinated.

Gandhi tells the story of a great leader but that doesn’t necessarily make it a great movie. In order to really examine Gandhi as a film, you have to be willing to accept that criticizing the movie is not the same as criticizing what (or who) the movie is about.

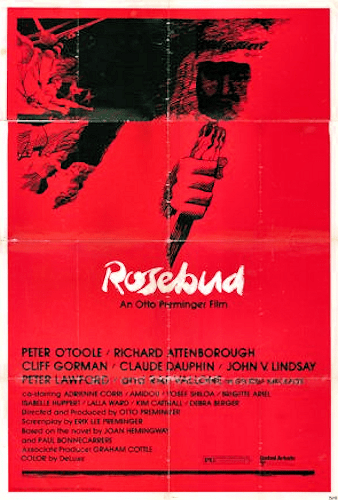

As I watched Gandhi, my main impression was that it was an extremely long movie. Reportedly, Gandhi was a passion project for director Richard Attenborough. An admirer of Gandhi’s and a lifelong equality activist, Attenborough spent over 20 years trying to raise the money to bring Gandhi’s life to the big screen. Once he finally did, it appears that Attenbrough didn’t want to leave out a single detail. Gandhi runs three and a half hours and, because certain scenes drag, it feels ever longer.

My other thought, as I watched Gandhi, was that it had to be one of the least cinematic films that I’ve ever seen. Bless Attenborough for the nobility of his intentions but there’s not a single interesting visual to be found in the entire film. I imagine that, even in 1982, Gandhi felt like a very old-fashioned movie. In the end, it feels more like something you would see on PBS than in a theater.

The film is full of familiar faces, which works in some cases and doesn’t in others. For instance, Gandhi’s British opponents are played by a virtual army of familiar character actors. Every few minutes, someone like John Gielgud, Edward Fox, Trevor Howard, John Mills, or Nigel Hawthorne will pop up and wonder why Gandhi always has to be so troublesome. The British character actors all do a pretty good job and contribute to the film without allowing their familiar faces to become a distraction.

But then, a few American actors show up. Martin Sheen plays a reporter who interview Gandhi. Candice Bergen shows up as a famous photographer. And, unlike their British equivalents, neither Sheen nor Bergen really seem to fit into the film. Both of them end up overacting. (Sheen, in particular, delivers every line as if he’s scared that we’re going to forget that we’re watching a movie about an important figure in history.) They both become distractions.

I guess the best thing that you can say about Gandhi, as a film, is that it features Ben Kingsley in the leading role. He gives a wonderfully subtle performance as Gandhi, making him human even when the film insists on portraying him as a saint. He won an Oscar for his performance in Gandhi and he deserved one.

As for Gandhi‘s award for best picture … well, let’s consider the films that it beat: E.T., Tootsie, The Verdict, and Missing. And then, consider some of the films from 1982 that weren’t even nominated: Blade Runner, Burden of Dreams, Class of 1984, Fast Times At Ridgemont High, My Favorite Year, Poltergeist, Tenebrae, Vice Squad, Fanny and Alexander…

When you look at the competition, it’s clear that the Academy’s main motive in honoring Gandhi the film was to honor Gandhi the man. In the end, Gandhi is a good example of a film that, good intentions aside, did not deserve its Oscar.