“She’s filled with secrets. Where we’re from, the birds sing a pretty song and there’s always music in the air.”

— The Man From Another Place (Michael Anderson) in Twin Peaks Episode 1.3, “Zen, or the Skill to Catch a Killer”

Oh my God, this is the episode with the dream!!!

Okay, a confession. Originally, this episode was not assigned to me. Originally, it was assigned to someone else. However, as soon as I realized that this was the episode that ended with the dream sequence, I begged and begged to be allowed to review it. I even cried a little.

Seriously, I love this episode.

Of course, when people talk about how “weird” Twin Peaks supposedly was, this is one of the episodes that they usually cite as evidence. They always mention that little man who speaks backwards and who dances in the room with the red curtains.

However, I think that labeling this episode — or, for that matter, anything else that David Lynch has directed — as merely being “weird” is a major misreading of Lynch’s signature style. When it comes to examining Lynch, it’s important to remember that, before he became a filmmaker, David Lynch was a painter. A David Lynch-directed film (or television episode) is essentially a moving painting. Often times, the plot is not to be found in the dialogue or what actually happens on screen. The plot is to be found in the mood that Lynch’s visuals create.

I once read an interview with Lynch where he talked about being fascinated by the fact that, if you removed bark from a tree, you could discover a very chaotic world happening underneath an otherwise genteel surface. All of his work has been about peeling back the outer layers of our world and seeing what lies underneath. When you think of this episode’s famous dream as just being another layer, one that is hidden until we close our eyes, shut off our assumptions, and go to sleep, you realize that there’s nothing strange about it.

It’s just Twin Peaks.

So, with all that in mind, let’s take a look at the third episode of Twin Peaks, “Zen, or the Skill to Catch A Killer.”

To say that we start with the opening credits probably sounds like the most obvious thing that I could possibly say conerning this episode but it’s still important to point out. The opening credits of Twin Peaks — the combination of the mill, the mountains, the road, and Angelo Badalamenti’s beautiful theme music — are absolutely brilliant. More than just letting you know what show you’re watching, the opening credits of Twin Peaks transport you into the world of this sordid little town.

To say that we start with the opening credits probably sounds like the most obvious thing that I could possibly say conerning this episode but it’s still important to point out. The opening credits of Twin Peaks — the combination of the mill, the mountains, the road, and Angelo Badalamenti’s beautiful theme music — are absolutely brilliant. More than just letting you know what show you’re watching, the opening credits of Twin Peaks transport you into the world of this sordid little town.

And what’s happening in Twin Peaks? It’s the third day of the Laura Palmer investigation. The homecoming queen who tutored Johhny Horn (Robert Bauer), taught Josie (Joan Chen) how to speak English, and helped organize the local Meals on Wheels program is still dead and a shocked town is still struggling to come terms with it. It all goes back to what I said earlier about how this show is all about peeling back layers and revealing what lies underneath. Though each episode may end with Laura’s blandly pretty homecoming photo, the layers underneath are full of chaos and secrets.

The episode opens with an awkward dinner with the Horne family. It’s Ben (Richard Beymer), Audrey (Sherilyn Fenn), Johnny, and Ben’s wife. They’re all sitting in a dining room that, like every room in Ben’s hotel, is completely made out of wood. (Again, you have to remember what Lynch said about the world underneath the bark.) Nobody speaks. It’s as awkward as that montage in Citizen Kane, the one where the collapse of Charles and Emily’s marriage is shown over the course of several increasingly strained breakfasts. But then Ben’s brother, Jerry (David Patrick Kelly), shows up. Jerry has just returned from Paris and he’s brought bread!

Up until this point, Ben has been a stiff figure, one who was largely defined by his greed. But when Jerry shows up, Ben’s face lights up and, almost like an animal, he bites into the bread. Why shouldn’t Ben be happy? Jerry is as flamboyant and eccentric as Ben was measured and closed off. (It helps that Jerry is played by David Patrick Kelly, who is one of those actors who can go totally over the top without losing his credibility or his charm. Before playing Jerry, Kelly achieved pop culture immortality by chanting, “Warriors, come out to play!” in 1979’s The Warriors.) When Jerry gets depressed at the news that the Norwegian deal fell through and that Laura Palmer’s dead, Ben suggests that they go to everyone’s favorite Canadian brothel, One-Eyed Jacks.

While we watch Ben and Jerry (undoubtedly named for everyone’s favorite Vermont capitalists) flirt with the lingerie-clad prostitutes at One-Eyed Jacks, we’re struck by just how dorky both of them truly are. The Hornes may be one of the richest and most powerful families in town but, emotionally, Ben and Jerry are children, still trying to impress each other with their stunted masculinity. The general ickiness of One-Eyed Jacks is nicely contrasted with a genuinely sweet scene of James Hurley (James Marshall) and Donna Hayward (Lara Flynn Boyle), wondering if they should feel guilty for being chastely attracted to each other so soon after Laura’s death.

Back at the hotel, Dale (Kyle MacLachlan) gets a call from Deputy Hawk (Michael Horse), informing him that a one-armed man has been seen wandering around the hospital. There’s a knock at the door. When Dale answers it, he finds only a note. It reads: “Jack with One Eye.”

Meanwhile, the three least likable people on the show — Bobby Briggs (Dana Ashbrook), Leo (Eric Da Re), and idiot Mike (Gary Hershberger) — get to have a scene of the very own. Bobby and Mike go out to the woods to pick up the drugs that they paid Leo for. Leo’s waiting for them, of course. He wants to know if Bobby knows who Shelley’s been cheating on him with. Since that person would be Bobby, Bobby is quick to say that he has no idea. It’s tempting to compare Bobby and Mike to Ben and Jerry. Whereas Ben and Jerry are rich and can pretty much indulge their vices without any fear of retribution, Bobby and Mike are still trying to reach that point. They still have to deal, on a face-to-face basis, with dangerous people like Leo. Again, I found myself looking that all trees, all the bark, and all the layers that surrounded Mike, Bobby, and Leo. Ben and Jerry may be rich but peel away and you’ll find Mike and Bobby. Mike and Bobby may be football stars but peel away and you’ll find Leo.

The next morning, life in Twin Peaks continues. Shelley (Madchen Amick), bruised from her latest beating, walks around the curiously unfinished home that she shares with Leo. When Bobby comes by and says that he’ll kill Leo if he ever hits Shelley again, they kiss and the camera zooms in on the bruise on Shelley’s jaw. When Ed Hurley (Everett McGill) gets yelled at for accidentally stepping on one of Nadine’s (Wendy Robie) drapes, he goes to the diner to see Norma (Peggy Lipton).

(Of all the minor characters in Twin Peaks, Nadine may seem like the most cartoonish but one should not be too quick to dismiss her. Her obsession with creating a silent drape runner may seem insane but actually, it’s an attempt to bring a little peace and order to an otherwise chaotic world. Nadine has become so obsessed with creating that peace that she doesn’t realize that she’s managed to alienate everyone around her. Her attempts to find perfection have only amounted in creating more chaos.)

It’s all a bit soapy and I don’t want to spend too much time on any of those subplots. Not in this review, anyway. What’s important is what Agent Cooper, Harry (Michael Ontkean), Hawk, Andy (Harry Goaz), and Lucy (Kimmy Robertson) are doing during all of this. If anyone had any doubt that Twin Peaks‘s version of the FBI is a bit different from the real world FBI, those doubts will be erased by the scene in which Cooper displays his investigative technique.

Out in the woods (and again, we’re reminded of the layers under the bark), Cooper has set up a blackboard. “By way of explaining what we’re about to do, I am first going to tell you a little bit about the country called Tibet…”

Cooper explains the sad history of Tibet and how Communist China forced the Dalia Lama into exile. “After having a dream three years ago,” Cooper woke up with much sympathy for the plight of the people Tibet and also with the knowledge of a new type of deductive technique.

That deductive skill comes down to throwing rocks at bottles while Sheriff Truman reads the name of every suspect whose name starts with a “J.” If Dale hits a bottle, Lucy is instructed to put a check mark next to that person’s name. Andy is sent down to stand near the bottle.

“I’m getting excited!” Andy shouts.

We all are, Andy.

Dale misses when Harry reads the names of James and Josie. But, when he says, “Lawrence Jacoby!,” the rock hits the bottle but does not break. “Make a note,” Dale says, regarding to the bottle not breaking, “that’s very important.”

The rest of the throws only lead to Andy getting bonked by a rock. At least, that is until the final throw. “Leo Johnson!” Harry says. Dale throws the rock. The bottle shatters.

As brilliant as MacLachlan is as Cooper, what really makes this scene work are the reactions of Harry, Hawk, Andy, and especially Lucy. Harry watches it all with a resigned but respectful skepticism. Hawk nods sagely as Cooper talks about the importance of being attuned with the spiritual world. Andy insists that it didn’t hurt when he got hit in the head by a rock. And Lucy gets totally and enthusiastically caught up in the minutiae of Cooper’s technique. When Harry says that “Jack with One Eye” is probably a reference to One-Eyed Jacks, Lucy very earnestly explains that she’s going to have to erase Jack With One Eye off of the list of suspects. By trying to apply logical rules to Cooper’s illogical technique, Lucy serves as a stand-in for the audience. The pure and sincere earnestness of Kimmy Robertson’s performance is one of the best things about his episode.

At the diner, the Hayward Family eats an after-church lunch when Audrey comes in and plays a song on the jukebox. Apparently, the jukebox only carries mood music written by Angelo Badalmenti. Donna and Audrey talk and the scene makes good use of the contrast between the two, Donna being the stereotypical good girl with secrets and Audrey being the artist who has been incorrectly typecast as a bad girl.

Back at the police station, Albert Rosenfield (Miguel Ferrer) shows up and I have to admit that I got a little bit choked up when I saw Ferrer looking so young and healthy. Albert is a forensic pathologist and he’s as abrasive as Dale is cheerful. If Dale immediately fell in love with small town life, Albert hates everything about it. Harry and Albert take an immediate dislike to each other, as well they should. But the thing with Albert is that it’s impossible to dislike him because he’s played by Miguel Ferrer. Ferrer could make even the most obnoxious of characters charming.

(Miguel Ferrer was the son of Jose Ferrer. I just recently watched the 1952 best picture nominee Moulin Rouge, which starred Jose as artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. If I hadn’t already known they were related, I would have guessed just from looking at Miguel in this episode. Miguel Ferrer died on January 7th of this year. He and his immense talent will certainly be missed.)

Night falls in Twin Peaks. Catherine (Piper Laurie) and Pete (Jack Nance) bicker. Leland Palmer (Ray Wise) deals with his grief by picking up Laura’s picture and dancing with it while Pennsylvania 6-5000 plays on a record player. “We have to dance for Laura!” Leland yells. (This scene is even more disturbing if you’ve seen Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me.)

And, back in his hotel room, Dale Cooper is having the dream.

(It’s interesting to note that, when Dale goes to bed, he wears the type of pajamas that you would normally expect to see a suburban dad in a 1950s sitcom wear. For all of his zen, Cooper truly is a symbol of what we think of as being a more innocent time.)

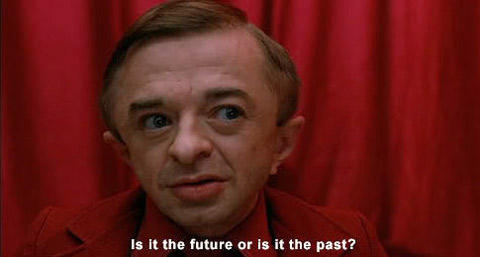

In his dream, a much older, gray-haired Dale Cooper sits in a room with red curtain. (The old age makeup that was put on MacLachlan for the dream sequence immediately made me think of Keir Dullea watching himself age, at the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey, before being reborn as a new being.) A little man — credited as being The Man From Another Place (Michael Anderson) — stands in a corner with his back to Dale and shakes in a way that almost seems obscene. Somewhere, perhaps behind the curtains, a distorted voice chants, “Laura! Laura!”

There are a succession of quick cuts. Mrs. Palmer (Grace Zabriskie) runs down the dark staircase in her house. The character who will eventually be known as Killer BOB (Frank Silva) stares menacingly at the viewer.

The one-armed man, who has wandered through the previous two episodes, appears and recites a poem: “Through the darkness of futures past/ The magician longs to see/ One chants out between two worlds/ Fire Walk With Me.” The one-armed man says that “we lived among the people. I think you say convenience store. We lived above it.” The man says that he was touched by the “devilish one.” He has a tattoo on his left shoulder but when the man saw the face of God, he chopped his arm off. “My name is Mike … his name is BOB.”

(Intentionally or not, we are reminded of another Mike and Bob who live in Twin Peaks. Could the Mike and BOB of Cooper’s dream but just layers of what lies underneath the two drug-dealing star football players? Is Cooper dreaming or is he just looking under the bark?)

BOB appears, sitting in what appears to be a boiler room, bringing to mind another film about a dream killer, Wes Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm Street. BOB, never one for subtlety, announces, “I’ll catch you with my death bag! You may think I’ve gone insane, but I promise, I will kill again!”

The older Cooper is back in the room with red curtains. The Man From Another Place continues to shake in the corner, his jerky movements almost mimicking masturbation. Meanwhile, Laura Palmer, in a black dress, sits across from Cooper and smiles.

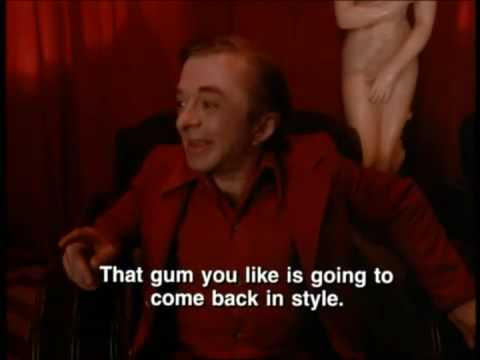

What follows is one of the best scenes in David Lynch’s legendary career. When The Man From Another Place finally turns around and starts to talk to Cooper, his voice has been dubbed backwards. The same is true of Laura when she speaks. We only know what they say because of the subtitles. It’s a very disconcerting effect, one that leaves us feeling as if the world is spinning in the wrong direction and might come off its axis at any moment.

The Man and Laura say a lot to Cooper. Some of what they say we know to be true. When The Man says that Laura is full of secrets, we know that he speaks the truth. When he says that Laura is not Laura but is instead his cousin (“but doesn’t she look like Laura Palmer,” he says) we may be confused but lovers of film noir will immediately think of Otto Preminger’s Laura, in which a detective thinks he’s falling in love with a dead woman until it’s revealed that the woman who was killed was not actually Laura but instead a look alike. (It has been suggested that Laura Palmer was specifically named after the title character in Preminger’s film.) When Laura says that, “Sometimes I feel like her but my arms bend back…,” it’s an obvious reference to the torture she endured in that railway car.

But there are other lines that only make sense if you’re willing to accept that they’re meant to be random. Why does the Man tells Cooper, “The gum you like is going to come back in style?” It could be an acknowledgement that the chivalrous and optimistic Cooper is a man out of time. Or it could just be something that the Man said to make conversation.

And why does the Man From Another Place dance at the end of the dream? That question gets asked more than any other and the answer is deceptively simple. If you know anything about the aesthetic of David Lynch, you know that the Man From Another Place dances just because he does. Things happen and, Lynch suggests, there often is no specific reason.

While the Man dances, Laura kisses Cooper. As I rewatched this scene, I particularly noticed that creepy way that the previously chaste Cooper smiled as Laura kissed him. It’s hard not to compare his smile to the somewhat goofy grin that decorated the face of Ben Horne when he visited One-Eyed Jacks at the start of this episode. Again, another layer has been peeled away and we’ve seen what lurks underneath.

Laura whispers in Cooper’s ear as the episode ends. What she says will have to wait for our next review. What’s important, for now, is that Cooper awakes, calls Harry, and announces, “I know who killed Laura Palmer!”

Previous Entries in The TSL’s Look At Twin Peaks: