Filmmaking in Japan has always thrived on extremes—but not in one uniform direction. On one end lies the haunting, gothic atmosphere of horror steeped in shadows, ritual, and psychological dread; on the other lies the explosion of ultra-violence, pushed to grotesque and sometimes cartoonish heights. This duality mirrors the country’s broader cultural and artistic history, from the impressionistic ritualism of Noh theater and kabuki to the stark contrasts found in ukiyo-e prints. It was inevitable that such traditions would shape Japanese cinema, inspiring films that swing between meditative stillness and overwhelming sensory assault. Few modern filmmakers embody this radical spectrum more vividly than Miike Takashi, the ever-provocative and unapologetically eclectic mad genius of Japanese film.

Trying to find a Western counterpart to Miike often feels impossible. He refuses to be pinned down, leaping from genre to genre with the same restless energy as a filmmaker like Steven Soderbergh, but with far darker, more transgressive tendencies. Yet even in his eclecticism, Miike tends to operate at the polar extremes of Japanese genre filmmaking. One year he delivers chillingly restrained, gothic atmosphere—as seen in Audition or One Missed Call, both sustained by mood, dread, and psychological unease. The next, he unleashes pure ultra-violence, as in Dead or Alive or Ichi the Killer, films that seem designed to push cinematic violence far beyond socially tolerable thresholds. He’s made yakuza dramas, samurai fantasies, children’s stories, westerns, thrillers, and even musicals. To watch Miike is to surrender to unpredictability—but always to expect extremity.

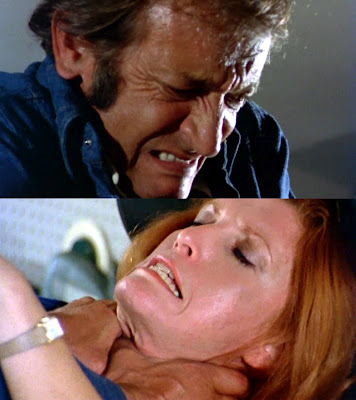

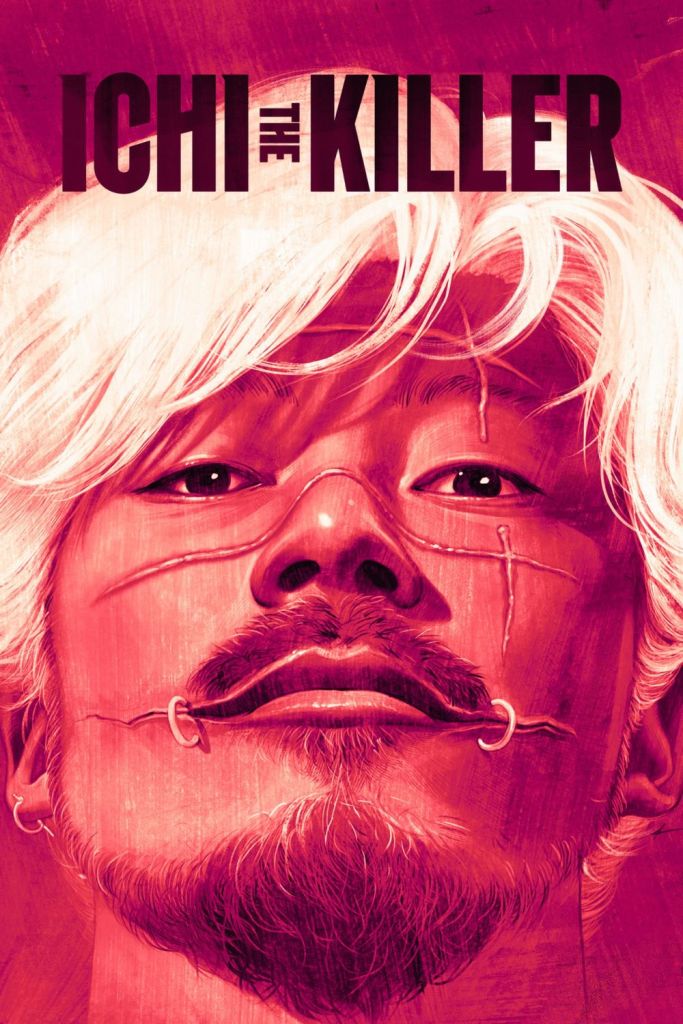

And nowhere is Miike’s fascination with the violent pole more vividly captured than in his infamous 2001 adaptation of Hideo Yamamoto’s manga Ichi the Killer (Koroshiya 1 in Japan). The film remains one of his boldest and most grotesque provocations: hallucinatory, hyper-violent, and defiantly sadomasochistic. If Audition showed Miike at his gothic and restrained, building terror through silence and stillness, then Ichi the Killer does the opposite—it blasts the viewer with sensory chaos, arterial spray, and sadomasochistic spectacle. The result pushes beyond gore into nightmare surrealism, so extreme it resembles Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch refracted through a carnival mirror.

On its surface, the narrative is deceptively straightforward: at its core lies the hunt between two men. Ichi, an emotionally fragile vigilante manipulated into becoming a weapon of destruction, and Kakihara, a flamboyant, sadistic yakuza enforcer who thrives on pain both given and received. While Miike alters aspects of the manga, he retains the dual narrative thread of these two figures spiraling toward an inevitable rooftop showdown high above Tokyo’s neon chaos. Yet to describe the plot too literally is pointless. Miike warps Yamamoto’s crime saga into something closer to a fever dream, a delirious collage of violence and grotesquerie where linear logic is slowly dissolved, leaving behind only sensation.

Where Ichi the Killer separates itself is in its layered subtext of body horror and sadomasochism. Miike is not content with gore alone; he explores the intimate psychology of pain and pleasure, showing their fusion in ways that unsettle. This is established from the film’s beginning, in one of its most infamous moments, when Ichi—lonely, voyeuristic, and lost in disturbing fantasies—masturbates while watching a prostitute being assaulted, climaxing onto a balcony railing. The explicitness shocks, but more importantly, it plants the film’s thematic flag: eroticism polluted by brutality, desire inseparable from cruelty. Miike ensures the audience feels implicated, not just as witnesses but as voyeurs who cannot look away.

Kakihara embodies the other side of this sadomasochistic spectrum. He lives for violence, both inflicting and enduring it. His Glasgow smile—cut into his cheeks years before Ledger’s Joker canonized the image—is carved symbol of his philosophy: rebellion scarred into flesh, grotesque yet strangely glamorous. Much of this impact rests on Tadanobu Asano’s performance. Watching him in this role today, it’s startling to compare Kakihara to his later mainstream work in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (Thor films) or the prestige Shōgun remake. The actor who once played measured dignity and stoicism there is here unchained, flamboyant, and feral. His Kakihara is rockstar-like, charismatic, terrifying, and magnetic; the performance feels like a primal howl that stands in stark contrast to his more restrained global roles. By the finale, one could argue Kakihara comes closer to the film’s “hero” than Ichi himself, embodying violence not merely as cruelty but as pure identity.

The film unfolds as a series of violent tableaux, each more outrageous than the last, somewhere between grotesque cartoon and waking nightmare. Bodies are mangled, organs splatter, arterial spray bursts like abstract expressionist brushstrokes. Miike pushes the imagery so far it sometimes tips into slapstick, calling to mind Peter Jackson’s Dead Alive. It’s violence past the point of horror, collapsing into absurdist comedy: as if Tom and Jerry were redrawn with box cutters and razor wire. Tarantino’s famous “House of Blue Leaves” sequence in Kill Bill clearly draws inspiration from Miike’s operatic bloodletting.

And yet Ichi the Killer is not mere shock and gore. Beyond its chaotic excess, the film probes violence as spectacle—something audiences recoil from but also consume with fascination. Miike refuses to let the audience off the hook. He doesn’t desensitize; he implicates. Watching Ichi means simultaneously condemning its cruelty and acknowledging our own morbid curiosity. That tension—between gothic atmospheres of dread and gaudy ultra-violence—is where Miike thrives.

This duality makes Ichi the Killer one of the most notorious entries in modern cult cinema. It isn’t for everyone, and was never intended to be. Some audiences will find it unwatchable, others mesmerizing. But what is undeniable is its extremity, one end of the spectrum of Japanese genre filmmaking stretched to breaking point. If Audition embodies Miike’s gothic restraint, Ichi represents his carnival of brutality. Together, they capture the twin poles of his artistry and of Japanese extremity itself. Violence here is more than gore—it is body horror, sadomasochism, and spectacle fused together, a dark carnival Miike dares us to enter and dares us not to look away.