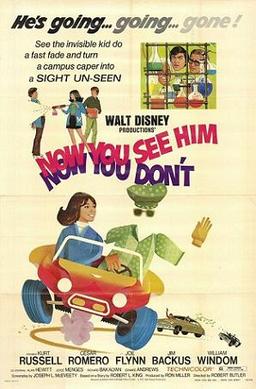

Dexter Riley (Kurt Russell) is back and just in time because Medfield College is on the verge of getting closed down again.

In The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes, buying a computer was supposed to be the solution to all of Medfield’s financial problems. I guess it didn’t work because Medfield is broke again and corrupt businessman A.J. Arnoe (Cesar Romero) is planning on canceling the school’s mortgage so that he can turn it into a casino.

There is some hope. Dexter has accidentally created an invisibility spray. Not only does it tun anything that it touches invisible but it also washes away with water so there’s no risk of disappearing forever. Dexter and his friend Schuyler (Michael McGreevey) know that they can win the science fair with their invention but the science fair doesn’t want to allow small schools like Medfield to compete unless they really have something big to offer. Dexter tells the Dean (Joe Flynn) that he has a sure winner but Dexter also refuses to reveal what it is because he doesn’t want word to leak before for the science fair. The Dean decides to raise the money to pay off the mortgage by becoming a golfer, as one does. Schulyer works as the Dean’s caddy while Dexter uses the invisibility spray to help the Dean cheat. That’s a good message for a young audience, Disney! But when Arno finds out about the spray, he wants to steal it so he can rob a bank.

This was even dumber than The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes but it was also hard to dislike it. The comedy was too gentle, Kurt Russell and the rest of the cast were too likable, and the special effects were too amusingly cheap in that retro Disney way for it to matter that the movie didn’t make any sense. When a bunch of college kids learn the secret of invisibility and use it to cheat at golf, you know you’re watching a Disney film.