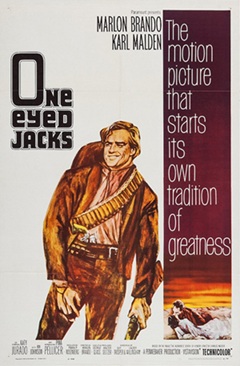

Rio (Marlon Brando), a young outlaw in the Old West, is betrayed by his partner and mentor Dad Longworth (Karl Malden) and ends up spending five years in a Mexican prison. When Rio escapes, he gets together a new gang and heads for Monterey, California. He wants to both get his revenge on Longworth and also rob the local bank. Things get complicated when Rio actually confronts Longworth and suddenly realizes that he can’t bring himself just to gun the man down in cold blood. Rio is not as ruthless of an outlaw as he thought he was.

Rio (Marlon Brando), a young outlaw in the Old West, is betrayed by his partner and mentor Dad Longworth (Karl Malden) and ends up spending five years in a Mexican prison. When Rio escapes, he gets together a new gang and heads for Monterey, California. He wants to both get his revenge on Longworth and also rob the local bank. Things get complicated when Rio actually confronts Longworth and suddenly realizes that he can’t bring himself just to gun the man down in cold blood. Rio is not as ruthless of an outlaw as he thought he was.

However, Rio then meets and falls in love with Louisa (Pina Pellicer), Longworth’s stepdaughter Longworth is willing to do whatever he has to keep Rio away from Louisa and, when Rio starts to think about going straight in an effort to win Louisa’s love, his new gang turn out to be even less trustworthy than his old partners.

A teenage rebellion film disguised as a western (and it’s not a coincidence that the main bad guy is named Dad), One-Eyed Jacks was Marlon Brando’s only film as a director. The film was originally meant to be directed by Stanley Kubrick, who was working from a script written by a once-in-a-lifetime combination of Rod Serling and Sam Peckinpah. Kubrick and Brando worked together to develop the film, with Brando insisting on Karl Malden as Dad. (Kubrick wanted to cast Spencer Tracy.) Ultimately realizing that working on One-Eyed Jacks would mean essentially taking orders from his star, Kubrick stepped down from directing so he could focus on Lolita and Brando took over as director. The film finally went into production in 1958 and would not be released until 1961. Brando’s perfectionism was blamed for the film going massively overbudget and, when it was finally released, One-Eyed Jacks was the first of Brando’s films to lose money. The combined box office failures of One-Eyed Jacks and the remake of Mutiny on the Bounty left Brando in the cinematic wilderness for much of the 60s.

As for the film itself, One-Eyed Jacks takes what should have been a simple story and attempts to turn into an epic. Rio spends a good deal of time brooding and the film seems to brood right along with him. What starts out as a western becomes a forbidden love story as Rio and Louisa fall for each other. Dad Longworth may be an outlaw-turned-sheriff but Malden plays him more as a possessive father who can’t handle that his two stepchildren — Rio and Louisa — are both turning against him and his strict rules. Brando obviously viewed the film as being something bigger than a standard western. Sometimes, his direction works and he does manage to get the epic feel that he was going for. Other times, the film itself seems to be unsure what direction it wants to go in telling its story. This is method directing.

Ultimately, One-Eyed Jacks is an interesting experiment, one that doesn’t really work but which still features Charles Lang’s outstanding cinematography and one of Karl Malden’s best performances. As Brando’s only directorial effort, the film is a curiosity piece, one that will be best enjoyed by western fans who have the patience for something a little different. And, for what it’s worth, based on the film’s visual beauty and the performances that he gets from the cat, I think Brando could have developed into a fine director with a little more experience. However, it was not to be.