“I have seen the dark universe yawning

Where the black planets roll without aim,

Where they roll in their horror unheeded,

Without knowledge, or lustre, or name.”

― H.P. Lovecraft, Nemesis

Tag Archives: Halloween

6 Days Til Halloween

6 Terrifying Trailers For October 25th, 2025

It’s only 6 days until Halloween!

Are you still struggling to get into the mood?

Don’t you worry! The latest edition is Lisa Marie’s Favorite Grindhouse Trailers is here to help you out!

Presented without comment, here are 6 classic trailers that are guaranteed to get you in the scary season mood….

- Carnival of Souls (1962)

2. Night of the Living Dead (1968)

3. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)

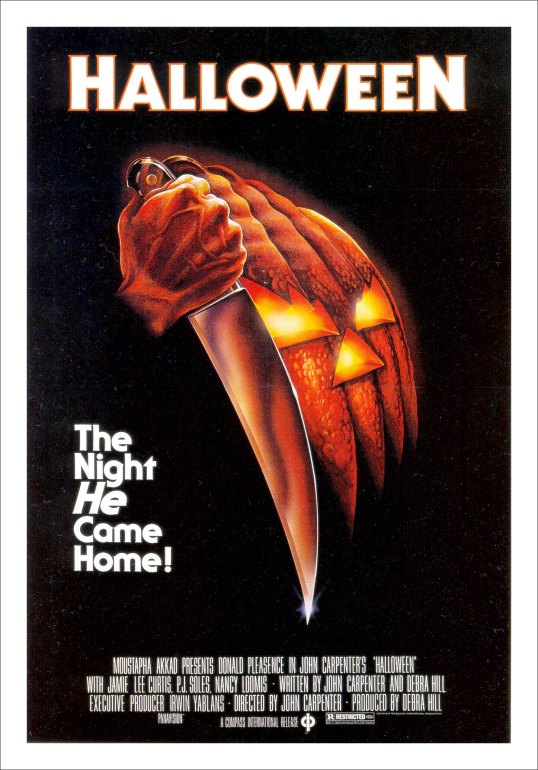

4. Halloween (1978)

5. Dawn of the Dead (1978)

6. Zombie (1979) (a.k.a. Zombi 2)

What do you think, Trailer Kiity?

I agree! Those trailers gave us a lot to think about!

Tide of Terror, AI Short Film Review by Case Wright

Clowns scare me and AI used to scare me, but I just don’t think it’s gonna be all that bad. I wasn’t going to review another AI short because…. well, they are terrible, BUT just as I was about to move on to real people- I saw this:

Lisa knows that I can’t turn down a shark movie or Torchy’s Tacos. A shark movie is like Torchy’s Tacos because even if they made mediocre taco- it’s still EXCELLENT. Furthermore, you are still eating a taco; so, how bad could your life really be?!

The short opens with a terribly flooded New York City. Uh oh, here comes a tidal wave and if that isn’t bad enough…. sharks…wait…no a lot sea creatures appear, which are kinda scary… to someone. I got halfway through and there’s something shark-like.

They cut away from the shark to a large squid; so, I’m like who brought the peanut oil? It’s time for some calamari!!! Finally, there is a shark again sort of… and zombies? Is it good? No, but there is a shark… so, fine. The short was all over the place and really tested the depths of punishing me. Then, Adele showed up because she’s….

If you want to check this short out….

Horror On TV: Raggedy Ann and Raggedy Andy in The Pumpkin That Wouldn’t Smile (dir by Chuck Jones)

Awwww, that poor pumpkin! Well, hopefully, he’s smiling now!

This animated special originally aired on Halloween night in 1979. I would imagine that the crying pumpkin probably traumatized children across America. Hopefully, all the kids were out trick or treating when this aired. Myself, I remember that when I was a kid, I would help my mom carve a pumpkin every year. And then I would get so depressed when we later had to throw it out. Seriously, I would get really attached to those jack o’lanterns.

Anyway, this cartoon is before my time but I have a feeling that, if I had been around to watch it, I would have been depressed for a whole year afterwards.

Enjoy!

4 Shots From 4 Horror Films: The 1970s Part 3

This October, I’m going to be doing something a little bit different with my contribution to 4 Shots From 4 Films. I’m going to be taking a little chronological tour of the history of horror cinema, moving from decade to decade.

Today, we close out the 70s!

4 Shots From 4 Films

Suspiria (1977, dir by Dario Argento)

Halloween (1978, dir by John Carpenter)

Zombi 2 (1979, dir by Lucio Fulci)

Horror On TV: The Great Bear Scare (dir by Hal Mason)

I came across this old cartoon on YouTube. Apparently, it aired in October of 1983.

It’s about bears living in Bearbank. Halloween is approaching and they’re worried about getting invaded by the monsters who live on Monster Mountain. Well, that makes sense. My question is why would you buy a house near a location called Monster Mountain? And really, shouldn’t the monsters be in the houses and the bears in the mountains? This cartoon is weird.

Anyway, the bears are getting ready to feel the city but little Ted E. Bear sets out to confront his fears! Woo hoo!

I don’t know. It’s from 1983. That was a strange year, I guess.

Enjoy!

Isolation to Madness: The Dark Genius of Carpenter’s Apocalypse Trilogy

“Reality’s not what it used to be.” – Sutter Cane

John Carpenter’s Apocalypse Trilogy is widely regarded as a foundational pillar of modern horror cinema, uniting three seemingly diverse films—The Thing (1982), Prince of Darkness (1987), and In the Mouth of Madness (1994)—under a singular thematic and philosophical canopy. Together, they explore cosmic horror, a subgenre of horror fiction that emphasizes humanity’s profound insignificance in a vast, indifferent, and often hostile universe. This trilogy traces a carefully crafted trajectory of escalating menace—from tangible physical fears to metaphysical anxieties, culminating in deep epistemological crises. By doing so, Carpenter’s trilogy challenges the audience’s very perceptions of reality, identity, and trust, pushing viewers to confront existential questions cloaked within horror narratives.

This study offers a comprehensive analysis of each film in sequence, revealing their major thematic concerns and unpacking Carpenter’s distinctive stylistic choices that unite the trilogy into one cohesive vision of apocalypse and despair. The analysis reveals that the trilogy extends beyond horror storytelling, engaging instead with the anxieties surrounding human perception, the limitations of knowledge, and cosmic insignificance.

John Carpenter and the Cosmic Horror Tradition

John Carpenter is celebrated for his ability to move beyond conventional scares, crafting atmospheric and philosophical horror that delves deeply into existential dread. While his debut with Halloween secured his place in slasher cinema, Carpenter’s Apocalypse Trilogy marks his most profound engagement with the tradition of cosmic horror, heavily influenced by the works of H.P. Lovecraft. These films focus less on conventional monsters and more on entities and forces beyond human comprehension that systematically erode sanity, faith, and the familiar social order.

In essence, Carpenter’s cosmic horror examines the frailty of human understanding in the face of vast, unknowable forces. His films suggest that the perceived stability of reality, morality, and identity are slender constructs that can unravel rapidly when exposed to those cosmic truths. This philosophical underpinning provides the connective tissue for the trilogy, positioning it as a sustained meditation on humanity’s precarious and often deluded sense of place within the universe.

Carpenter combines his hallmark minimalist aesthetic with unsettling soundscapes to create settings steeped in dread and uncertainty. These environments refuse to offer comfort or clarity. Instead, they become spaces where reality’s veneer thins, paranoia grows, and the audience is drawn into the slow disintegration of order.

The Thing: The Anatomy of Isolation and Paranoia

The trilogy begins in the frozen desolation of an Antarctic research station—a brutally unforgiving landscape depicted through Carpenter’s distinct minimalist style. The opening, consisting of sweeping, stark aerial shots paired with Ennio Morricone’s haunting bass synth score, plunges viewers into an environment defined by isolation and claustrophobia.

The physical environment functions as an active force in the story, enhancing tension and alienation. It becomes impossible for the characters—and the audience—to escape the oppressive atmosphere, emphasizing themes of entrapment and despair.

Carpenter’s adaptation of Campbell’s Who Goes There? foregrounds psychological horror, centering around an alien organism that perfectly imitates any living creature it infects. This ability destroys the survivors’ social cohesion, as the possibility that anyone might be the alien breeds constant suspicion and fear. The alien infection acts metaphorically, symbolizing humanity’s deepest anxieties about identity, otherness, and contamination.

Rob Bottin’s practical special effects remain iconic, transforming the concept of body horror into palpable cinematic terror. Scenes such as the infected dogs blending with the humans visually communicate the indivisibility of friend and foe, reinforcing the thematic belief that not even one’s own body is fully trustworthy.

The film’s ambiguous finale, where the surviving characters share an uneasy, silent distrust, masterfully underscores existential despair. Echoing Sartre’s famous assertion that “Hell is other people,” Carpenter closes with no clear resolution, reinforcing a bleak worldview that permeates the entire trilogy.

Prince of Darkness: When Science Meets Metaphysical Terror

The second chapter shifts from Antarctic physicality to a metaphysical siege within a Los Angeles church, where scientists and clergy confront a cryptic green liquid imprisoning an ancient quantum entity identified as Satan. Carpenter weaves a thematic collision between faith and science, positioning the characters in a supernatural standoff that tests the limits of rational belief.

This paradigm collision is central to the film’s tension. Characters engage in empirical inquiry and theological reflection, yet neither fails to fully grasp or control the cosmic forces unleashed. Dreams broadcast across neural networks, quantum mechanics concepts, and disorienting visions unravel the sense of coherent reality and blur lines between the physical and the spiritual.

Mirrors act as critical motifs, symbolizing portals or gateways that problematize identity and perception. As reality itself becomes infected and fractured, the boundaries between natural and supernatural, self and Other, disintegrate. This thematic decay anticipates the disintegration of reality that reaches its apex in In the Mouth of Madness. The siege allegory encapsulates humanity’s futile attempts to impose order over chaos.

In the Mouth of Madness: The Apocalypse of the Mind

The trilogy culminates in a meta-textual horror narrative tracing John Trent, an insurance investigator ensnared by the vanishing horror novelist Sutter Cane. This film explores the erosion of reality and identity as Trent journeys into a fictional world that becomes concrete, gradually dissolving the distinctions between fact and fiction, sanity and madness.

Drawing explicitly on Lovecraftian ideas of forbidden knowledge and cosmic despair, Carpenter situates the archetypal theme in a modern media environment. Cane’s novels exert a parasitic force upon readers, triggering apocalyptic psychological and ontological shifts that implicate society itself.

The narrative layering intensifies to a climax wherein Trent watches a film adaptation of his destructive unraveling, collapsing the barrier between spectator and spectacle. This recursive structure evokes chilling reflection on the instability of identity and reality.

The phrase “losing me” becomes a haunting leitmotif. Characters’ gradual loss of selfhood illustrates cosmic horror’s existential core: the dissolution of individuality under the weight of incomprehensible cosmic forces, a theme central to the trilogy as a whole.

Escalating Terror: From Bodily Invasion to Psychic Annihilation

This collection of films explores a profound and unsettling meditation on humanity’s place in an uncaring, vast cosmos, using horror as a lens to examine themes of isolation, paranoia, faith, knowledge, and the tenuous nature of reality. Without explicitly presenting themselves as a connected series, they create a rich thematic tapestry that invites viewers to contemplate not only external terrors but the fragility of human systems meant to protect meaning and identity.

The opening confronts the visceral and physical: a mysterious alien force invades bodies, dissolving trust and social cohesion. This invasion is deeply symbolic, reflecting fears of contamination, loss of self, and the breakdown of community ties. The body becomes a battleground where identity is no longer stable, and the enemy might be anyone—including oneself. This phase grounds horror in concrete fears but already sows the seeds of existential uncertainty.

From there, the narrative moves to a metaphysical plane where science, religion, and philosophy—humanity’s traditional pillars of understanding—struggle and fail to contain an ever-spreading cosmic evil. This shift from physical threat to metaphysical chaos illustrates how human knowledge and faith are insufficient to explain or confront the vast, dark unknown. The intermingling of scientific inquiry and religious dread reveals a universe that defies compartmentalized understanding, forcing a reckoning with ambiguity and the unknown. With reality itself starting to fray at the edges, the threat becomes more abstract yet no less terrifying.

The final movement confronts the fragility of perception and reality itself. As realities collapse, identities dissolve, and narrative and truth blur, the horror becomes psychological and epistemological—loss of sanity, loss of self, loss of a stable world. This breakdown reveals the highest level of terror, where nothing can be trusted, no truth is certain, and reality is malleable. It captures the profound human fear of mental disintegration and the obliteration of meaning in an indifferent universe.

Together, these stages chart a journey from external bodily threat to metaphysical disruption and ultimately to existential collapse. They reveal horror not just as fear of outward monsters but as internal decay of mind, belief, and identity, underscoring human vulnerability not only to external forces but to the fragility of cognition and existence. This arc reflects deep anxieties about human limitations: no matter the knowledge or faith, cosmic forces remain beyond control, making certainty an illusion. By layering escalating horrors, the films engage on emotional and intellectual levels, inviting lasting reflection on fear, reality, and humanity’s place in the cosmos.

The Limitations of Human Knowledge

Across all three films in John Carpenter’s Apocalypse Trilogy, the limits of human knowledge are a central theme. Characters—whether scientists, clergy, or ordinary people—try to impose order and meaning on forces they cannot understand or control. But they consistently face phenomena far beyond their cognition, revealing the fragility of human certainty. This motif challenges anthropocentrism and critiques human arrogance by exposing absolute truth and certainty as illusions in a vast, indifferent cosmos.

In The Thing, the alien defies identification or control, sowing paranoia among the survivors. Scientific tests fail, and certainty dissolves into fear that anyone could be the monster. The alien symbolizes the unknown randomness and uncontrollability threatening human identity and social bonds.

Prince of Darkness deepens this theme by confronting the limits of both science and faith. A cosmic evil trapped in a mysterious liquid defies both scientific and religious understanding. The film blurs boundaries between science, theology, and metaphysics, suggesting human knowledge is incomplete and vulnerable to forces beyond comprehension. The inevitability of apocalypse underscores the insufficiency of human understanding.

In In the Mouth of Madness, epistemological collapse is central. Reality and fiction merge, and the protagonist loses grip on truth. Carpenter suggests reality depends on belief and narrative, making truth unstable. This reveals the ultimate vulnerability of human cognition and identity.

Together, these films show that no human system—scientific, religious, or cultural—can fully grasp or control the universe’s nature. This breeds existential horror, highlighting human fragility and limited knowledge on a cosmic scale.

Carpenter’s trilogy aligns with Lovecraftian cosmic horror, updating its themes with contemporary anxieties. The films go beyond simple scares to challenge viewers to confront the fragility of knowledge, reality, and identity, giving the trilogy lasting philosophical weight and emotional power.

Stylistic Mastery: Minimalism and Ambiguity

Carpenter’s hallmark minimalist style is a key part of what makes the Apocalypse Trilogy so effective and enduring in its impact. His careful framing often restricts what the audience can see, focusing attention on essential details while leaving much to the imagination. This approach compels viewers to fill in unseen gaps themselves, which creates heightened suspense and engages the viewer’s own fears. Rather than overwhelming the audience with explicit gore or frantic action, subdued movements and carefully controlled pacing allow tension to build slowly and organically. This slow burn style deepens engagement by forcing the audience into a state of heightened alertness and anticipation.

Carpenter’s sound design is equally important to the films’ mood. Low-frequency drones and eerie synth scores envelop viewers in an unsettling sonic atmosphere that mirrors the creeping dread in the story. These soundscapes don’t seek to startle but to create pervasive unease—a feeling that danger lurks just beyond perception. The music often mimics the alien or supernatural presence itself—unpredictable, cold, vast—helping to reinforce themes of existential dread and the incomprehensibility of the cosmic forces involved.

The combination of minimalism in visuals and sound creates a liminal space where reality feels unstable and disorienting. Audiences experience not only the narrative horror but also a profound sense of ambiguity and existential uncertainty. This stylistic restraint deliberately avoids clear answers or visual excess, underlining the theme that the real terror is ineffable and beyond human understanding. The unknown and unseen become the most frightening elements, much in line with the tradition of cosmic horror that Carpenter’s trilogy embodies.

In addition, ambiguity in character behavior and narrative direction invites multiple interpretations. Questions are often left unanswered—What exactly is the alien’s goal? How much control do the characters really have? What is the nature of the “darkness” in Prince of Darkness? This lack of closure compels viewers to wrestle with uncertainty and the limits of human cognition, mirroring the trilogy’s philosophical concerns.

In integrating this stylistic mastery, Carpenter crafts a cinematic experience that is not merely about monsters or scares but about immersing viewers in the unsettling, unstable space where human understanding falters. This immersive uncertainty evokes the core cosmic horror concept: that our place in the universe is fragile, our perceptions unreliable, and the forces around us ultimately unknowable.

Subtextual Depth and Cultural Legacy

These three films transcends traditional horror by engaging deeply with contemporary anxieties about faith, knowledge, identity, and the influence of mass media on how reality is perceived. It reflects the emotional and intellectual struggles of postmodern individuals trying to navigate a fragmented, uncertain world. Rather than offering simple resolution or catharsis, Carpenter’s bleak vision portrays apocalypse as a slow, creeping dissolution of human confidence and coherence. This approach adds philosophical weight and emotional resonance that have secured the trilogy’s lasting impact on horror cinema and cosmic horror traditions.

The films challenge viewers to confront fears beyond the supernatural or monstrous, focusing instead on the fragility of belief systems and the vulnerability of identity in a world where truth is unstable. By threading themes of epistemological uncertainty and spiritual crisis throughout, the trilogy mirrors the postmodern condition, where mass media distorts reality, and personal and collective certainties erode. Carpenter’s work thus becomes an exploration not only of cosmic terror but also of cultural disintegration and psychological fragility.

This subtextual richness extends the trilogy’s legacy beyond genre boundaries, influencing later horror films and narratives that explore existential dread and the human condition’s limits. The trilogy’s refusal to simplify or resolve its themes encourages ongoing reflection on the nature of fear, reality, and human understanding — making it a profound philosophical statement as well as a cinematic achievement.

The Enduring Power of Carpenter’s Dark Vision

The Apocalypse Trilogy by John Carpenter is far more than a collection of horror films; it is a profound meditation on humanity’s fragility, the dissolution of trust, and the shattering of reality itself. Through The Thing, Carpenter explores the primal fear of isolation and the collapse of social bonds when faced with an enemy that hides among us, perfectly embodying the horror of paranoia and mistrust. Moving into Prince of Darkness, the trilogy confronts the collision of science and faith, unraveling the foundations of knowledge and belief as cosmic evil seeps into the rational world and forces characters to confront metaphysical chaos. Finally, In the Mouth of Madness pushes this existential crisis to its zenith, dismantling the very concept of reality and identity through a meta-narrative that implicates not only its characters but also its viewers in the apocalypse of the mind.

What ties these films together, beyond surface narrative dissimilarities, is their shared thematic obsession with the limits of human understanding and the erosion of the self. Each film intensifies the scale of horror—from bodily invasion to spiritual contagion to the complete annihilation of the individual’s perception of reality—revealing Carpenter’s uniquely bleak worldview steeped in Lovecraftian cosmic horror. Through restrained yet evocative stylistic choices, utilizing minimalist visuals and sound design, Carpenter immerses audiences in atmospheres of claustrophobia, dread, and creeping madness. This underlines a core message: true horror lies not in external monsters but in the internal unravelling of everything we rely on—trust, faith, and the coherence of reality.

The Apocalypse Trilogy is a quintessential study of “losing me,” a phrase echoed in In the Mouth of Madness but foreshadowed throughout the series. It captures a universal existential anxiety about identity’s fragility in the face of implacable, incomprehensible forces. Carpenter’s films, in their relentless exploration of despair and dissolution, resist offering hope or redemption, instead presenting apocalypse not as spectacular destruction but as a slow, inevitable erosion of the human condition itself.

John Carpenter’s Apocalypse Trilogy stands as a landmark achievement in horror cinema and cosmic horror literature adaptation. It confronts viewers with unsettling questions about what makes us human and how easily those foundations may crumble. More than a trilogy of scares, it is a dark genius unfolding in three acts—charting a terrifying journey “from isolation to madness” that challenges the very nature of reality, faith, and the self. It demands that we not only watch the horror but reckon with the unsettling possibility that within each of us lies the capacity for both fear and dissolution in equal measure.

Horror Scenes That I Love: Dr. Loomis Explains Michael Myers in the original Halloween

We’ve talked a bit about Donald Pleasence today. Pleasence is one of my favorite actors, an intense performer with an eccentric screen presence who always gave it his all, even in films that didn’t always seem like they deserved the effort. Pleasence was a character actor at heart and he appeared in a wide variety of films. He’s absolutely heart-breaking in The Great Escape, for instance. However, it seems that Pleasence is destined to be best-remembered for his horror roles. For many, he will always be Dr. Sam Loomis, the oracle of doom from the original Halloween films.

In this scene from the original Halloween, Dr. Loomis (Donald Pleasence) attempts, as best he can, to explain the unexplainable. I’ve always felt that Pleasence’s performance in the first film is extremely underrated. People always tend to concentrate on the scenes where he gets angry and yells or the later films where an obviously fragile Pleasence was clearly doing the best he could with poorly written material. But, to me, the heart of Pleasence’s performance (and the film itself) is to be found in this beautifully delivered and haunting monologue.

In this scene, we see that Dr. Loomis is himself a victim of Michael Myers. Spending the last fifteen years with Michael has left Loomis shaken and obviously doubting everything that he once believed. Whenever I watch both Halloween and its sequel, I always feel very bad for Dr. Loomis. Not only did he have to spend 15 years with a soulless psychopath but, once Michael escapes, he has to deal with everyone blaming him for it. Dr. Loomis was literally the only person who saw Michael for what he was.

Incidentally, Donald Pleasence nearly turned down the role of Sam Loomis. He didn’t think there was much to the character. (The role had already been offered to Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing, neither of whom were interested.) It was his daughter, Angela Pleasence, who persuaded Donald to take the role. At that year’s Cannes Film Festival, Angela saw John Carpenter’s Assault on Precinct 13 and she assured her father that Carpenter was a talented filmmaker. Taking his daughter’s advice, Donald Pleasence accepted the role and, by all accounts, was a complete gentleman and a professional on set. After making horror history as Dr. Sam Loomis, Pleasence would go on to appear in two more Carpenter films, Escape from New York and Prince of Darkness.

Horror Song of the Day: Mr. Sandman by The Chordettes

Our first Horrorthon song of the day probably seems like an obvious choice. That’s okay, though. Thanks to John Carpenter, this sweet little song about teen love became an anthem of impending horror. None of the Chordettes are with us anymore. I would love to know what they may or may not have thought about Carpenter’s use of their song in Halloween.

I’d like to think they would have appreciated it. Michael Myers may not have had hair like Liberace but he did have a mask that looked a lot like William Shatner.

Mr. Sandman, bring me a dream (bom, bom, bom, bom)

Make him the cutest that I’ve ever seen (bom, bom, bom, bom)

Give him two lips like roses and clover (bom, bom, bom, bom)

Then tell him that his lonesome nights are over

Sandman, I’m so alone (bom, bom, bom, bom)

Don’t have nobody to call my own (bom, bom, bom, bom)

Please turn on your magic beam

Mr. Sandman, bring me a dream

Mr. Sandman, bring me a dream

Make him the cutest that I’ve ever seen

Give him the word that I’m not a rover

Then tell him that his lonesome nights are over

Sandman, I’m so alone

Don’t have nobody to call my own

Please turn on your magic beam (woah)

Mr. Sandman, bring me a dream

Mr. Sandman (yes?) bring us a dream

Give him a pair of eyes with a “come-hither” gleam

Give him a lonely heart like Pagliacci

And lots of wavy hair like Liberace

Mr. Sandman, someone to hold (someone to hold)

Would be so peachy before we’re too old

So please turn on your magic beam

Mr. Sandman, bring us

Please, please, please, Mr. Sandman

Bring us a dream

Songwriters: Clifford Smith / Robert F. Diggs / Jason S. Hunter