(At Night by Erin Nicole)

“There are horrors beyond life’s edge that we do not suspect, and once in a while man’s evil prying calls them just within our range.”

The Thing on the Doorstep (H.P. Lovecraft)

(At Night by Erin Nicole)

“There are horrors beyond life’s edge that we do not suspect, and once in a while man’s evil prying calls them just within our range.”

The Thing on the Doorstep (H.P. Lovecraft)

“You’re diving deeper than any sane man ever should.” — Dr. Katherine McMichaels

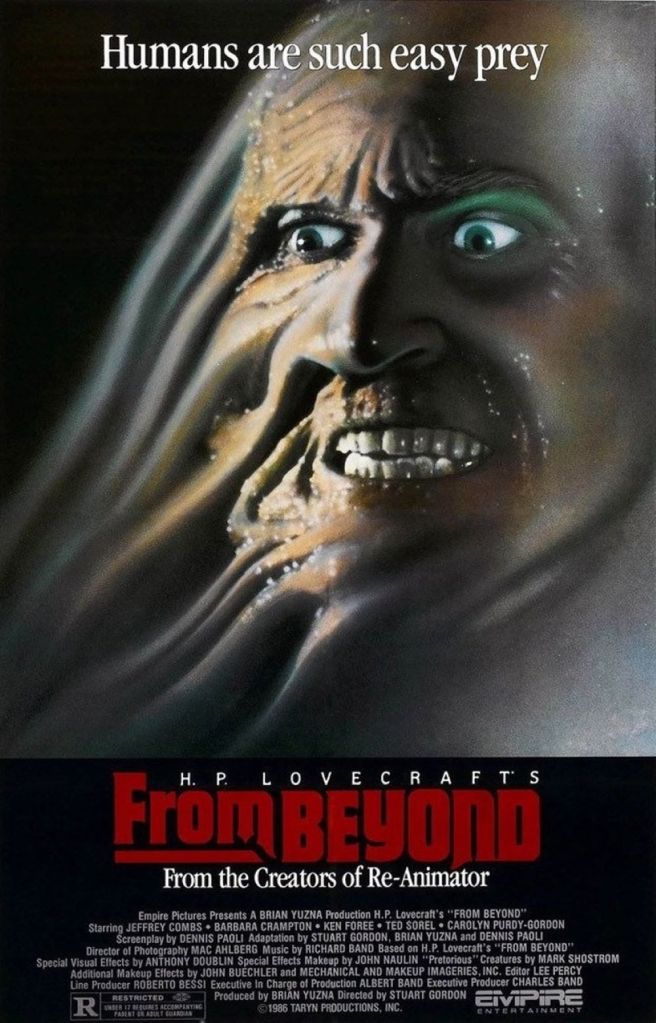

Stuart Gordon’s From Beyond (1986) stands as a darker, moodier follow-up to his breakout Lovecraft adaptation, Re-Animator (1985). At its core is the Resonator, a bizarre scientific contraption designed to stimulate the pineal gland—allowing its users to glimpse eerie creatures and dimensions normally invisible to the naked eye. When Dr. Crawford Tillinghast (Jeffrey Combs) activates the device, it unleashes horrors not just upon the world but also within the minds and bodies of those involved, blurring the line between reality and nightmare in a way both terrifying and hypnotic.

Just like with Re-Animator, Gordon used H.P. Lovecraft’s short story From Beyond as a foundation but expanded the narrative significantly by injecting his own creative vision and filling in what Lovecraft left unexplored. Lovecraft’s original story is a brief, eerie vignette about stimulating the pineal gland to perceive alternate dimensions and terrifying alien creatures—minimalistic and atmospheric, leaving much to the imagination. Gordon reimagines this premise into a fully fleshed-out narrative, adding complex characters like the obsessive Dr. Edward Pretorius and the rational yet vulnerable Dr. Katherine McMichaels. He enriches the story with body horror, psychological torment, and a deeper thematic exploration of sexuality, obsession, and the fragility of the mind. This creative expansion transforms the story into something far more personal and tangible, blending cosmic horror with primal human fears and desires.

This tonal shift stands in stark contrast to Re-Animator, which thrives on anarchic gore, slapstick comedy, and a playful mad-scientist energy. From Beyond trades much of the humor for a somber, unsettling atmosphere drenched in slime, grotesque transformations, and claustrophobic dread. The characters are more grounded in psychological trauma, and the film’s pacing emphasizes creeping unease rather than chaotic spectacle. Gordon’s use of stark, hallucinatory lighting and saturated colors enhances this otherworldly feeling, while practical effects bring a tactile horror to life that heightens the visceral and emotional impact. The horror isn’t just external—it’s internal, a fracture of reality and self.

One of the most notable ways From Beyond separates itself from Gordon’s earlier work is in its overt intertwining of sexuality and horror. The Resonator doesn’t just expose alien creatures; it unlocks primal lust and repressed desires in its users. Scenes imbued with uneasy erotic tension, especially involving Barbara Crampton’s character, make sexuality a core source of vulnerability and terror. This blend of eroticism and nightmare adds depth and psychological complexity, exploring how intimate human experiences can be distorted into something terrifying. It’s a thematic boldness that would become highly influential beyond Western cinema.

Indeed, the film’s fusion of sexual subtext, body horror, and psychological unease foreshadowed themes embraced by late 1980s and early 1990s Japanese horror hentai anime. Works such as Angel of Darkness (Injū Kyōshi) combined explicit eroticism, grotesque body transformations, and supernatural horror in ways reminiscent of From Beyond’s style and tone. This synergy helped define a subgenre of adult horror anime where the boundaries between pleasure and terror, desire and monstrosity, are constantly blurred—cementing From Beyond not only as a cult classic in horror but also as an inspirational bridge to pioneering adult animation in Japan.

Visually and atmospherically, the film is a masterpiece of practical effects and immersive storytelling. The slime-drenched creatures, anatomically warped bodies, and constant visual flow between nightmare and distorted reality create a hallucinatory experience. The climax offers a frenetic, visceral battle that embodies the film’s core themes of madness, transformation, and cosmic terror, leaving viewers with a lingering sense of unease and wonder.

Stuart Gordon’s direction also employs incredibly effective subjective perspectives, with many scenes shot from the characters’ points of view. This technique immerses viewers in the unfolding madness and heightens the sensory overload that defines the film’s experience. There is a famously unsettling point-of-view shot from the mutated Crawford as he perceives a brain inside a doctor’s head and gruesomely attacks. Such moments amplify the film’s exploration of altered perception and the treacherous expansion of human senses.

Despite these strengths, the film is not without flaws. Ken Foree’s character, Bubba Brownlee, while providing moments of grounded streetwise humor, sometimes comes off as a caricature that leans into stereotypical portrayals of Black men as taboo or outlier figures in horror cinema. This portrayal feels somewhat jarring against the film’s otherwise nuanced tone and may evoke discomfort.

Additionally, From Beyond can feel comparatively stiff and sluggish next to Re-Animator, lacking some of the earlier film’s darkly comic energy. The story often relies on a series of increasingly grotesque set pieces that feel more like shock showcases than a cohesive narrative arc. Some performances, including Jeffrey Combs’ lead, occasionally seem overly intense without sufficient emotional variation, and the film sometimes slips into melodrama that undercuts its impact. Furthermore, although ambitious in visualizing Lovecraftian horrors, budgetary constraints are occasionally evident, diminishing some of the awe those moments seek to inspire.

Ultimately, Gordon’s From Beyond is a significant Lovecraft adaptation that showcases the power of expanding upon source material with bold creativity. Moving beyond Lovecraft’s sparse prose, Gordon infuses the story with rich characters, psychological depth, explicit body horror, and mature explorations of sexuality. This results in a haunting, distinctly unsettling film that not only stands as a high point in Gordon’s career but also resonates far beyond its American horror roots, shaping international horror aesthetics and inspiring future genres. It is a disturbing, thrilling journey to the dark spaces just beyond human perception—a cinematic experience that lingers in the mind long after the screen fades to black.

“Reality’s not what it used to be.” – Sutter Cane

John Carpenter’s Apocalypse Trilogy is widely regarded as a foundational pillar of modern horror cinema, uniting three seemingly diverse films—The Thing (1982), Prince of Darkness (1987), and In the Mouth of Madness (1994)—under a singular thematic and philosophical canopy. Together, they explore cosmic horror, a subgenre of horror fiction that emphasizes humanity’s profound insignificance in a vast, indifferent, and often hostile universe. This trilogy traces a carefully crafted trajectory of escalating menace—from tangible physical fears to metaphysical anxieties, culminating in deep epistemological crises. By doing so, Carpenter’s trilogy challenges the audience’s very perceptions of reality, identity, and trust, pushing viewers to confront existential questions cloaked within horror narratives.

This study offers a comprehensive analysis of each film in sequence, revealing their major thematic concerns and unpacking Carpenter’s distinctive stylistic choices that unite the trilogy into one cohesive vision of apocalypse and despair. The analysis reveals that the trilogy extends beyond horror storytelling, engaging instead with the anxieties surrounding human perception, the limitations of knowledge, and cosmic insignificance.

John Carpenter is celebrated for his ability to move beyond conventional scares, crafting atmospheric and philosophical horror that delves deeply into existential dread. While his debut with Halloween secured his place in slasher cinema, Carpenter’s Apocalypse Trilogy marks his most profound engagement with the tradition of cosmic horror, heavily influenced by the works of H.P. Lovecraft. These films focus less on conventional monsters and more on entities and forces beyond human comprehension that systematically erode sanity, faith, and the familiar social order.

In essence, Carpenter’s cosmic horror examines the frailty of human understanding in the face of vast, unknowable forces. His films suggest that the perceived stability of reality, morality, and identity are slender constructs that can unravel rapidly when exposed to those cosmic truths. This philosophical underpinning provides the connective tissue for the trilogy, positioning it as a sustained meditation on humanity’s precarious and often deluded sense of place within the universe.

Carpenter combines his hallmark minimalist aesthetic with unsettling soundscapes to create settings steeped in dread and uncertainty. These environments refuse to offer comfort or clarity. Instead, they become spaces where reality’s veneer thins, paranoia grows, and the audience is drawn into the slow disintegration of order.

The trilogy begins in the frozen desolation of an Antarctic research station—a brutally unforgiving landscape depicted through Carpenter’s distinct minimalist style. The opening, consisting of sweeping, stark aerial shots paired with Ennio Morricone’s haunting bass synth score, plunges viewers into an environment defined by isolation and claustrophobia.

The physical environment functions as an active force in the story, enhancing tension and alienation. It becomes impossible for the characters—and the audience—to escape the oppressive atmosphere, emphasizing themes of entrapment and despair.

Carpenter’s adaptation of Campbell’s Who Goes There? foregrounds psychological horror, centering around an alien organism that perfectly imitates any living creature it infects. This ability destroys the survivors’ social cohesion, as the possibility that anyone might be the alien breeds constant suspicion and fear. The alien infection acts metaphorically, symbolizing humanity’s deepest anxieties about identity, otherness, and contamination.

Rob Bottin’s practical special effects remain iconic, transforming the concept of body horror into palpable cinematic terror. Scenes such as the infected dogs blending with the humans visually communicate the indivisibility of friend and foe, reinforcing the thematic belief that not even one’s own body is fully trustworthy.

The film’s ambiguous finale, where the surviving characters share an uneasy, silent distrust, masterfully underscores existential despair. Echoing Sartre’s famous assertion that “Hell is other people,” Carpenter closes with no clear resolution, reinforcing a bleak worldview that permeates the entire trilogy.

The second chapter shifts from Antarctic physicality to a metaphysical siege within a Los Angeles church, where scientists and clergy confront a cryptic green liquid imprisoning an ancient quantum entity identified as Satan. Carpenter weaves a thematic collision between faith and science, positioning the characters in a supernatural standoff that tests the limits of rational belief.

This paradigm collision is central to the film’s tension. Characters engage in empirical inquiry and theological reflection, yet neither fails to fully grasp or control the cosmic forces unleashed. Dreams broadcast across neural networks, quantum mechanics concepts, and disorienting visions unravel the sense of coherent reality and blur lines between the physical and the spiritual.

Mirrors act as critical motifs, symbolizing portals or gateways that problematize identity and perception. As reality itself becomes infected and fractured, the boundaries between natural and supernatural, self and Other, disintegrate. This thematic decay anticipates the disintegration of reality that reaches its apex in In the Mouth of Madness. The siege allegory encapsulates humanity’s futile attempts to impose order over chaos.

The trilogy culminates in a meta-textual horror narrative tracing John Trent, an insurance investigator ensnared by the vanishing horror novelist Sutter Cane. This film explores the erosion of reality and identity as Trent journeys into a fictional world that becomes concrete, gradually dissolving the distinctions between fact and fiction, sanity and madness.

Drawing explicitly on Lovecraftian ideas of forbidden knowledge and cosmic despair, Carpenter situates the archetypal theme in a modern media environment. Cane’s novels exert a parasitic force upon readers, triggering apocalyptic psychological and ontological shifts that implicate society itself.

The narrative layering intensifies to a climax wherein Trent watches a film adaptation of his destructive unraveling, collapsing the barrier between spectator and spectacle. This recursive structure evokes chilling reflection on the instability of identity and reality.

The phrase “losing me” becomes a haunting leitmotif. Characters’ gradual loss of selfhood illustrates cosmic horror’s existential core: the dissolution of individuality under the weight of incomprehensible cosmic forces, a theme central to the trilogy as a whole.

This collection of films explores a profound and unsettling meditation on humanity’s place in an uncaring, vast cosmos, using horror as a lens to examine themes of isolation, paranoia, faith, knowledge, and the tenuous nature of reality. Without explicitly presenting themselves as a connected series, they create a rich thematic tapestry that invites viewers to contemplate not only external terrors but the fragility of human systems meant to protect meaning and identity.

The opening confronts the visceral and physical: a mysterious alien force invades bodies, dissolving trust and social cohesion. This invasion is deeply symbolic, reflecting fears of contamination, loss of self, and the breakdown of community ties. The body becomes a battleground where identity is no longer stable, and the enemy might be anyone—including oneself. This phase grounds horror in concrete fears but already sows the seeds of existential uncertainty.

From there, the narrative moves to a metaphysical plane where science, religion, and philosophy—humanity’s traditional pillars of understanding—struggle and fail to contain an ever-spreading cosmic evil. This shift from physical threat to metaphysical chaos illustrates how human knowledge and faith are insufficient to explain or confront the vast, dark unknown. The intermingling of scientific inquiry and religious dread reveals a universe that defies compartmentalized understanding, forcing a reckoning with ambiguity and the unknown. With reality itself starting to fray at the edges, the threat becomes more abstract yet no less terrifying.

The final movement confronts the fragility of perception and reality itself. As realities collapse, identities dissolve, and narrative and truth blur, the horror becomes psychological and epistemological—loss of sanity, loss of self, loss of a stable world. This breakdown reveals the highest level of terror, where nothing can be trusted, no truth is certain, and reality is malleable. It captures the profound human fear of mental disintegration and the obliteration of meaning in an indifferent universe.

Together, these stages chart a journey from external bodily threat to metaphysical disruption and ultimately to existential collapse. They reveal horror not just as fear of outward monsters but as internal decay of mind, belief, and identity, underscoring human vulnerability not only to external forces but to the fragility of cognition and existence. This arc reflects deep anxieties about human limitations: no matter the knowledge or faith, cosmic forces remain beyond control, making certainty an illusion. By layering escalating horrors, the films engage on emotional and intellectual levels, inviting lasting reflection on fear, reality, and humanity’s place in the cosmos.

Across all three films in John Carpenter’s Apocalypse Trilogy, the limits of human knowledge are a central theme. Characters—whether scientists, clergy, or ordinary people—try to impose order and meaning on forces they cannot understand or control. But they consistently face phenomena far beyond their cognition, revealing the fragility of human certainty. This motif challenges anthropocentrism and critiques human arrogance by exposing absolute truth and certainty as illusions in a vast, indifferent cosmos.

In The Thing, the alien defies identification or control, sowing paranoia among the survivors. Scientific tests fail, and certainty dissolves into fear that anyone could be the monster. The alien symbolizes the unknown randomness and uncontrollability threatening human identity and social bonds.

Prince of Darkness deepens this theme by confronting the limits of both science and faith. A cosmic evil trapped in a mysterious liquid defies both scientific and religious understanding. The film blurs boundaries between science, theology, and metaphysics, suggesting human knowledge is incomplete and vulnerable to forces beyond comprehension. The inevitability of apocalypse underscores the insufficiency of human understanding.

In In the Mouth of Madness, epistemological collapse is central. Reality and fiction merge, and the protagonist loses grip on truth. Carpenter suggests reality depends on belief and narrative, making truth unstable. This reveals the ultimate vulnerability of human cognition and identity.

Together, these films show that no human system—scientific, religious, or cultural—can fully grasp or control the universe’s nature. This breeds existential horror, highlighting human fragility and limited knowledge on a cosmic scale.

Carpenter’s trilogy aligns with Lovecraftian cosmic horror, updating its themes with contemporary anxieties. The films go beyond simple scares to challenge viewers to confront the fragility of knowledge, reality, and identity, giving the trilogy lasting philosophical weight and emotional power.

Carpenter’s hallmark minimalist style is a key part of what makes the Apocalypse Trilogy so effective and enduring in its impact. His careful framing often restricts what the audience can see, focusing attention on essential details while leaving much to the imagination. This approach compels viewers to fill in unseen gaps themselves, which creates heightened suspense and engages the viewer’s own fears. Rather than overwhelming the audience with explicit gore or frantic action, subdued movements and carefully controlled pacing allow tension to build slowly and organically. This slow burn style deepens engagement by forcing the audience into a state of heightened alertness and anticipation.

Carpenter’s sound design is equally important to the films’ mood. Low-frequency drones and eerie synth scores envelop viewers in an unsettling sonic atmosphere that mirrors the creeping dread in the story. These soundscapes don’t seek to startle but to create pervasive unease—a feeling that danger lurks just beyond perception. The music often mimics the alien or supernatural presence itself—unpredictable, cold, vast—helping to reinforce themes of existential dread and the incomprehensibility of the cosmic forces involved.

The combination of minimalism in visuals and sound creates a liminal space where reality feels unstable and disorienting. Audiences experience not only the narrative horror but also a profound sense of ambiguity and existential uncertainty. This stylistic restraint deliberately avoids clear answers or visual excess, underlining the theme that the real terror is ineffable and beyond human understanding. The unknown and unseen become the most frightening elements, much in line with the tradition of cosmic horror that Carpenter’s trilogy embodies.

In addition, ambiguity in character behavior and narrative direction invites multiple interpretations. Questions are often left unanswered—What exactly is the alien’s goal? How much control do the characters really have? What is the nature of the “darkness” in Prince of Darkness? This lack of closure compels viewers to wrestle with uncertainty and the limits of human cognition, mirroring the trilogy’s philosophical concerns.

In integrating this stylistic mastery, Carpenter crafts a cinematic experience that is not merely about monsters or scares but about immersing viewers in the unsettling, unstable space where human understanding falters. This immersive uncertainty evokes the core cosmic horror concept: that our place in the universe is fragile, our perceptions unreliable, and the forces around us ultimately unknowable.

These three films transcends traditional horror by engaging deeply with contemporary anxieties about faith, knowledge, identity, and the influence of mass media on how reality is perceived. It reflects the emotional and intellectual struggles of postmodern individuals trying to navigate a fragmented, uncertain world. Rather than offering simple resolution or catharsis, Carpenter’s bleak vision portrays apocalypse as a slow, creeping dissolution of human confidence and coherence. This approach adds philosophical weight and emotional resonance that have secured the trilogy’s lasting impact on horror cinema and cosmic horror traditions.

The films challenge viewers to confront fears beyond the supernatural or monstrous, focusing instead on the fragility of belief systems and the vulnerability of identity in a world where truth is unstable. By threading themes of epistemological uncertainty and spiritual crisis throughout, the trilogy mirrors the postmodern condition, where mass media distorts reality, and personal and collective certainties erode. Carpenter’s work thus becomes an exploration not only of cosmic terror but also of cultural disintegration and psychological fragility.

This subtextual richness extends the trilogy’s legacy beyond genre boundaries, influencing later horror films and narratives that explore existential dread and the human condition’s limits. The trilogy’s refusal to simplify or resolve its themes encourages ongoing reflection on the nature of fear, reality, and human understanding — making it a profound philosophical statement as well as a cinematic achievement.

The Enduring Power of Carpenter’s Dark Vision

The Apocalypse Trilogy by John Carpenter is far more than a collection of horror films; it is a profound meditation on humanity’s fragility, the dissolution of trust, and the shattering of reality itself. Through The Thing, Carpenter explores the primal fear of isolation and the collapse of social bonds when faced with an enemy that hides among us, perfectly embodying the horror of paranoia and mistrust. Moving into Prince of Darkness, the trilogy confronts the collision of science and faith, unraveling the foundations of knowledge and belief as cosmic evil seeps into the rational world and forces characters to confront metaphysical chaos. Finally, In the Mouth of Madness pushes this existential crisis to its zenith, dismantling the very concept of reality and identity through a meta-narrative that implicates not only its characters but also its viewers in the apocalypse of the mind.

What ties these films together, beyond surface narrative dissimilarities, is their shared thematic obsession with the limits of human understanding and the erosion of the self. Each film intensifies the scale of horror—from bodily invasion to spiritual contagion to the complete annihilation of the individual’s perception of reality—revealing Carpenter’s uniquely bleak worldview steeped in Lovecraftian cosmic horror. Through restrained yet evocative stylistic choices, utilizing minimalist visuals and sound design, Carpenter immerses audiences in atmospheres of claustrophobia, dread, and creeping madness. This underlines a core message: true horror lies not in external monsters but in the internal unravelling of everything we rely on—trust, faith, and the coherence of reality.

The Apocalypse Trilogy is a quintessential study of “losing me,” a phrase echoed in In the Mouth of Madness but foreshadowed throughout the series. It captures a universal existential anxiety about identity’s fragility in the face of implacable, incomprehensible forces. Carpenter’s films, in their relentless exploration of despair and dissolution, resist offering hope or redemption, instead presenting apocalypse not as spectacular destruction but as a slow, inevitable erosion of the human condition itself.

John Carpenter’s Apocalypse Trilogy stands as a landmark achievement in horror cinema and cosmic horror literature adaptation. It confronts viewers with unsettling questions about what makes us human and how easily those foundations may crumble. More than a trilogy of scares, it is a dark genius unfolding in three acts—charting a terrifying journey “from isolation to madness” that challenges the very nature of reality, faith, and the self. It demands that we not only watch the horror but reckon with the unsettling possibility that within each of us lies the capacity for both fear and dissolution in equal measure.

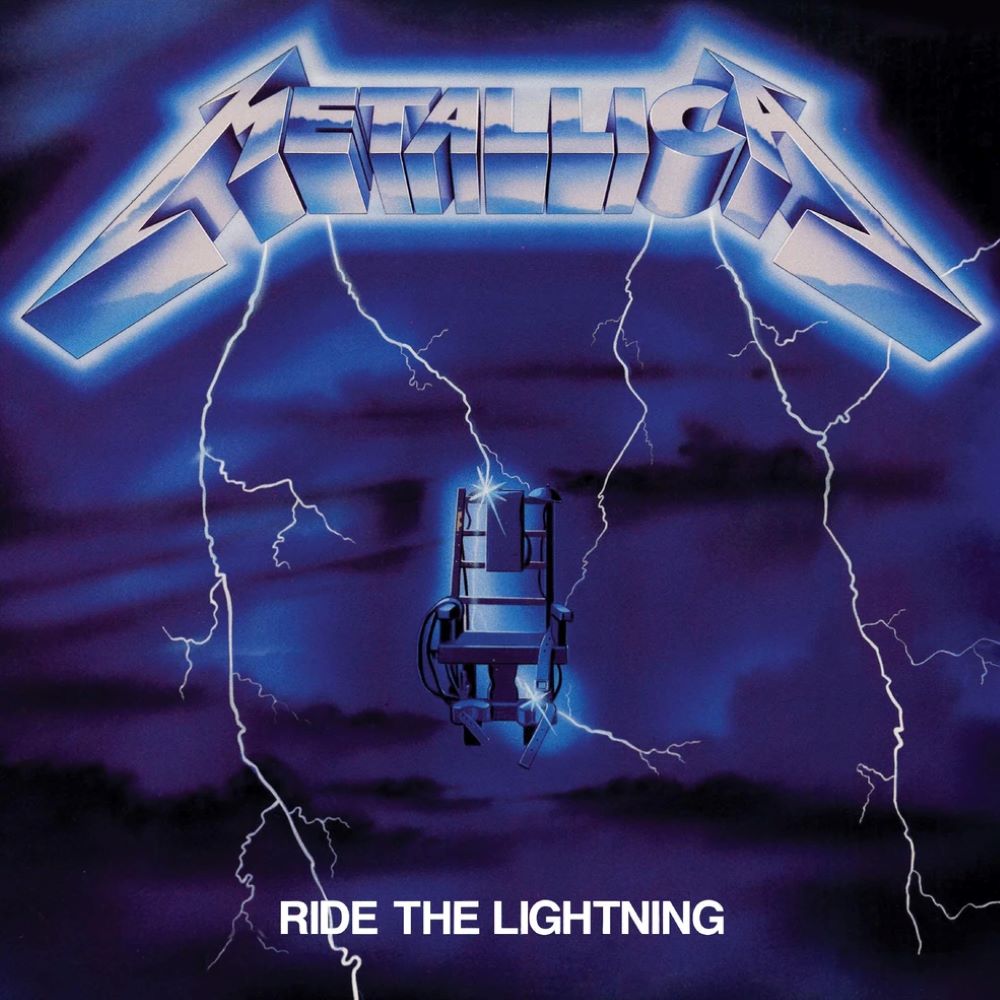

Metallica’s “The Call of Ktulu” is like an eerie soundtrack to something ancient and terrifying lurking just beneath the surface. The whole song feels like a slow, deliberate wake-up call for an otherworldly monster straight out of Lovecraft’s nightmares. Without any lyrics, it’s the music itself that tells the story—starting off quiet and haunting, then gradually building layers of tension like the air getting heavier before a storm, pulling you into an unsettling experience of growing dread.

What’s cool is how each instrument adds its own flavor to that feeling. Cliff Burton’s bass rumbles low and deep, almost like the sea itself is grumbling, while the guitars slowly creep in with sharp, sometimes almost claw-like riffs. Lars Ulrich’s drums keep everything feeling urgent without rushing it, like the heartbeat of something big and unstoppable. It’s not just playing metal riffs; it’s like they’re painting a picture of a cosmic beast stirring from an ancient sleep, and you can’t look away even though you’re scared.

Interestingly, “The Call of Ktulu” was initially started by Dave Mustaine before his dismissal from Metallica, but it ultimately became a collaborative piece among all four original band members. Released as part of their 1984 album Ride the Lightning, the song reached new heights when performed with the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra on the live album S&M. The legendary composer Michael Kamen arranged and conducted the orchestral parts, adding sweeping strings and powerful brass that turned the track into an apocalyptic ritual of sound, blending Metallica’s heavy riffs with symphonic grandeur and amplifying the song’s cosmic horror vibe to an unforgettable level.

Look at me/I’m Sandra Dee….

First released in the groovy and psychedelic year of 1970, The Dunwich Horror stars Sandra Dee as Nancy, an somewhat innocent grad student at Massachusetts’s Miskatonic University. When the mysterious Wilbur Wheatley (Dean Stockwell) comes to the university and asks to take a look at a very rare book called The Necronomicon, Nancy agrees. She does so even though there’s only one edition of The Necronomicon in existence and it’s supposed to be protected at all costs. Maybe it’s Wilbur’s hypnotic eyes that convince Nancy to allow him to see and manhandle the book. Prof. Henry Armitage (Ed Begley) is not happy to see Wilbur reading the book and he warns Nancy that the Wheatleys are no good.

Nancy still agrees to give Wilbur a ride back to his hometown of Dunwich. She finds herself enchanted by the mysterious Wilbur and she’s intrigued as to why so many people in the town seem to hate Wilbur and his father (Sam Jaffe). Soon, she is staying at Wilbur’s mansion and has apparently forgotten about actually returning to Miskatonic. She has fallen under Wilbur’s spell and it soon becomes clear that Wilbur has sinister plans of his own. It’s time to start chanting about the Old Ones and the eldritch powers while naked cultists run along the beach and Nancy writhes on an altar. We are in Lovecraft county!

Actually, it’s tempting to wonder just how exactly H.P. Lovecraft would have felt about this adaptation of his short story. On the one hand, it captures the chilly New England atmosphere of Lovecraft’s work and it features references to such Lovecraft mainstays as Miskatonic University, the Necronomicon, and the Old Ones. As was often the case with Lovecraft’s stories, the main characters are students and academics. At the same time, this is very much a film of the late 60s/early 70s. That means that there are random naked hippies, odd camera angles, and frequent use of the zoom lens. The film makes frequent use of solarization and other psychedelic effects that were all the rage in 1970. Lovecraft may have been an unconventional thinker but I’m still not sure he would have appreciated seeing his fearsome cult transformed into a bunch of body-painting hippies.

Really, the true pleasure of The Dunwich Horror is watching a very earnest Sandra Dee act opposite a very stoned Dean Stockwell. Stockwell was a charter member of the Hollywood counterculture, a friend of Dennis Hopper’s who had gone from being a top Hollywood child actor to playing hippie gurus in numerous AIP films. As for Sandra Dee, one gets the feeling that this film was an attempt to change her square image. When Wilbur tells Nancy that her nightmares sound like they’re sexual in origin and then explores her feelings about sex, Nancy replies, “I like sex,” and it’s obviously meant to be a moment that will make the audience say, “Hey, she’s one of us!” But Sandra Dee delivers the line so hesitantly that it actually has the opposite effect. Stockwell rather smoothely slips into the role of the eccentric Wilbur. Wilbur is meant to be an outsider and one gets the feeling that’s how Stockwell viewed himself in 1970. Sandra Dee, meanwhile, seems to be trying really hard to convince the viewer that she’s not the same actress who played Gidget and starred in A Summer Place, even though she clearly is. It creates an oddly fascinating chemistry between the two of them. Evil Wilbur actually comes across as being more honest than virtuous Nancy.

Executive produced by Roger Corman, The Dunwich Horror is an undeniably campy film but, if you’re a fan of the early 70s grindhouse and drive-in scene, it’s just silly enough to be entertaining. Even when the film itself descends into nonsense, Stockwell’s bizarre charisma keeps things watchable and there are a few memorable supporting performances. (Talia Shire has a small but memorable roll as a nurse.) It’s a film that stays true to the spirit of Lovecraft, despite all of the hippies.

1988’s The Unnamable takes place in the type of small, superstitious town that H.P. Lovecraft made famous in his stories. (The Unnamable is loosely based on Lovecraft’s work.)

The students at Miskatonic University are fascinated by the stories that surround the old Winthrop place, a mansion where, 100 years ago, Joshua Winthrop’s wife supposedly gave birth to a hideous monster that proceeded to kill Joshua and all of his servants. It is said that the mansion is still haunted, perhaps by the ghost of Joshua or maybe by the monster itself! The students regularly dare each other to stay at the old Winthrop Place. Joel (Mark Parra) accepts the dare and vanishes, worrying his friends Howard Damon (Charles Klausmeyer) and Randolph Carter (Mark Kinsey Stephenson). While Howard is a skeptic about the supernatural, Carter is a dedicated student and he’s obsessed with what might be found within the Winthrop house.

Meanwhile, two frat boys (Eben Ham and Blane Wheatley) convince Wendy (Laura Albert) and Tanya (Alexandra Durrell) to come hang out with them for the night in the Winthrop House. The frat boys claim that it’s an annual initiation that all new students go through. For the most part, the frat boys just want to get laid. One of them even drapes a sweater over his shoulders. Since when has anyone wearing a sweater that way turned out to be a good guy?

Of course, it turns out that Winthrop House is haunted and soon, heads are rolling (literally) and blood is being spilled. While the frat boys and the girls fight for their lives, Howard and Carter break into the mansion to see if they can find their missing friend Joel. Of course, Carter is immediately distracted by the mansion’s collection of ancient texts and hidden tunnels. Howard, on the other hand, just wants to save Wendy’s life and prove that he’s as good as any sweater-draping frat boy.

The Unnamable is fairly low-budget affair, one that mixes the slasher genre with Lovecraft’s chilly horror. It works surprisingly well. The house is a wonderfully atmospheric location. The monster, when it finally makes its appearance, is frightening and very Lovecraftian. In fact, the monster feels as if could have wandered over from Stuart Gordon’s Castle Freak. (The Unnamable probably would never have been made if not for the success of Gordon’s Re-Animator.) The gore is plentiful and, at times, disturbingly convincing. The main thing that makes The Unnamable work as well as it does is that the cast is surprisingly game and they attack their stereotypical roles with a likable enthusiasm. Nobody coasts on the fact that the film is just a “horror movie” or just as “slasher flick.” The characters may not have much depth but the cast still does a good job of bringing them to life (and death). I especially liked the performance of Mark Kinsey Stephenson as Randolph Carter. Randolph Carter, of course, is a name that should be familiar to most Lovecraft readers and Stephenson is a delight as he ignore the chaos around him so that he can check out the mansion’s library. While the film definitely takes some liberties with Lovecraft, Stephenson is still the ideal Carter.

The Unnamable was an enjoyably macabre surprise.

1989’s Dark Heritage deals with the aftermath of a violent thunderstorm in Louisiana.

After the thunder has rumbled and the lightning has flashed and all of the rain has fallen, several dead bodies are discovered in the wilderness near a mansion. Why are the bodies out there? How did they end up dead? Are they connected to the reclusive Dansen clan, a once notorious family that may not even exist any more? Bearded reporter Clint Harrison (Mark LaCour) is sent to find out!

Dark Heritage is an example of one of my favorite genres, the low-budget regional horror film. Dark Heritage not only takes place in Louisiana but it was also filmed in Louisiana with a cast that spoke in genuine Louisiana accents. It wouldn’t surprise me to learn that the majority of the crew was from the state as well. This is not one of those films where the South is represented by the mountains of California. That brings a certain amount of authenticity to the production and that authenticity can make up for a lot. This film captures the true atmosphere of Louisiana at its most humid and gothic and there aren’t any yankees around to ruin everything. That’s always nice.

At the same time, Dark Heritage also wears its low-budget on its sleeve. Sometimes, it’s effective. A sepia-clad vision of a ghostly member of the Dansen clan entering the mansion and motioning for the reporter to follow him is far more effective than it has any right to be. The horror genre is one of the few genres that actually benefits from grainy cinematography and dark lighting. There are other times when the amateurishness of the production is definitely a distraction. A scene towards the end where a man threatens Clint with a gun is so overacted by everyone involved that it actually becomes rather humorous to watch. If the most intense scene of your horror film inspires laughter instead of a racing heart, it’s definitely a problem.

The film itself is loosely based on H.P. Lovecraft’s The Lurking Fear. Just as with the original story, we get an extended sequence of an underground chamber that is full of some genuinely creepy monsters. That said, the film’s plot is often not that easy to follow, both because of the illogical actions of the characters and also some genuinely poor sound recording that makes it difficult to follow the conversations. This is a film where Clint first goes to the mansion with two companions. When those companions disappear, Clint is told that he is now a murder suspect. Clint’s reaction is to go find someone else to return to the house with him. Surely he knows that if that person also dies while visiting the house, he’ll look even more guilty. I mean, that would only make sense, right? Why not just stay away from the house?

Dark Heritage has a lot of atmosphere and it even manages to give us a few memorable and creepy visuals. That said, it’s ultimately done in by its low-budget and its often incoherent plot.

2024’s The Old Ones opens with an animated sequence of an old sea captain being tossed into a light, an apparent sacrifice. On the one hand, it’s properly macabre, featuring as it does a cult sacrifice. On the other hand, it’s also kind of cute because it’s animated. That juxtaposition between the horrific and the cute pretty much defines the entire film.

The sea captain is Russell Marsh (Robert Miano). He eventually washes up, 95 years after he left his home on a sea voyage. Russell is discovered by Dan (Scott Vogel) and his son, Gideon (Brandon Philip), who are camping and having some father-and-son bonding time. Russell tells them that he was born in 1865 and that he last set sail in 1930. Dan and Gideon point that’s not possible because it’s 2025 and Russell doesn’t appear to be a day over 65. Russell says that he’s spent the last 95 year being possessed and controlled by the Old Ones, the cosmic beings who control the universe. Dan is skeptical but then Dan is promptly killed by a monster who materializes out of nowhere. Russell and Gideon go on the run, trying to avoid cultists and others who have been possessed by the Old Ones. Russell says that, if he can find the mysterious Nylarlahotep, he may be able to travel through time and stop himself from going to sea in 1930. Russell would never be possessed by the Old Ones and, in theory, Gideon’s father would never had died.

The Old Ones is “based on the writings of H.P. Lovecraft” and it should be noted that the film does contain references to a lot of Lovecraft’s stories. Nylarlahotep (played here by Rico E. Anderson) is a character straight out of Lovecraft and his behavior here — menacing and enigmatic, if slightly bemused by the foolishness of humanity — very much conforms to Lovecraft’s portrayal of him. The Old Ones will be familiar to anyone with even a passing knowledge of the Cthulhu Mythos. That said, the film itself doesn’t always feel particularly Lovecraftian, if just because of the amount of humor that is found during Russell and Gideon’s quest. Gideon is often in a state of shock while Russell is the one who has seen it all and faces every horror with a studied nonchalance.

(One of the film’s best moments is when Russell pragmatically suggests that Gideon should sacrifice himself since Russell is just going to reverse time anyways.)

Considering that the budget was obviously low and that the writings of H.P. Lovecraft are notoriously difficult to adapt, The Old Ones works far better than I certainly expected it to. The story moves quickly and even the humor adds to the overall feel of the chaotic energy of the Old Ones invading human existence. The strongest thing about the film is the performance as Robert Miano as Russell Marsh. As played by Miano, Russell is the perfect hero for this type of story, compassionate but also pragmatic enough not to shed any tears if someone happens to die on Russell’s way to reversing time. Even if the humor may not reflect the source material, the film still ends on a very Lovecraftian note. One person’s happy ending is another’s nightmare.

2005’s The Call of Cthulhu is several stories in one.

In a mental hospital, an apparent madman (Matt Foyer) talks to his psychiatrist (John Bolen) about the death of his uncle, a professor who had similarly gone made during his final days. The man’s uncle was obsessed with evidence of a worldwide cult who worshipped an ancient being, perhaps named Cthulhu and perhaps sleeping somewhere in the ocean. When his uncle died, the man received all of his research. The files detailed the discovery of a cult in Louisiana, with the added caveat that the man who discovered the cult himself died under mysterious circumstances. Later a boat is found floating at sea and the records within suggest that the boat’s crew met a fearsome creature on a dark and stormy night. As soon becomes clear, the price for investigating Cthulhu is losing one’s own sanity. Once a researcher realizes that Cthulhu and the Old Ones are real and that the universe really is beyond understanding or human control, insanity inevitably follows.

H.P. Lovecraft’s The Call of Cthulhu was originally published in 1928 and it remains Lovecraft’s best-known work. It’s often cited as the start of the Cthulhu mythos, though Lovecraft had hinted at Cthulhu’s existence in previous stories. Lovecraft was a prolific correspondent who kept in contact with other pulp writers and who allowed them to add to the Cthulhu mythos. As a result, it seems as if writing a Cthulhu story has become a rite of passage for many aspiring horror writers. (Even Stephen King has written a few.) H.P. Lovecraft may have not been a household name when he died but Cthulhu ensured his immortality.

Why has Cthulhu had the impact that it has? I think the answer is right there in the story. As the characters come to realize, Cthulhu is beyond understanding and, because it cannot be understood, it cannot be defeated. Cthulhu and the other Great Old Ones are beyond humanity’s traditional concepts of good and evil. Whereas other monsters can be defined and often defeated by what they want, Cthulhu is beyond such concerns. Not even the members of his cult really seem to be sure just what exactly it is that they’re going to gain from their worship.

Cthulhu represents powerlessness of humanity in the face of a cold and uncaring universe. Cthulhu represents chaos. There is no way to fight Cthulhu but, because Cthulhu is such an enigma, intellectually curious humans (and Lovecraft’s protagonists often were academics) find themselves drawn to him. But the minute one starts to research Cthulhu, they are inevitably drawn to their destruction. The same is probably true of people who specifically read short stories and watch movies about Cthulhu. We’re all doomed. I hope this hasn’t ruined your Wednesday.

The Call of Cthulhu was long-considered to be unfilmable but, in 2005, director Andrew Leman proved the skeptics worng. Realizing that The Call of Cthulhu was the epitome of 1920s horror, Leman made the clever decision to adopt the story in the style of a 20s-silent film. The black-and-white cinematography is gorgeous, the title cards perfectly capture the melodramatic tone of 20s cinema (and they also help with the fact that Lovecraft’s dialogue doesn’t always sound natural when spoken aloud), and the largely practical effects capture the haunting horror of Lovecraft’s vision. The moment when the boat’s crew meets Cthulhu at sea is especially well done, with the stop-motion effects proving themselves to be far more effective than any CGI could be. The end result is a film pays tribute to Lovecraft while also bringing to life the mystery of Cthulhu.