Bret Maverick (James Garner) stops off and visits his old friend Jed Christianson (Edgar Buchanan). Jed is desperate to break up the hot and heavy romance between his beautiful and wild daughter, Carrie (Abby Dalton), and a good for nothing gunslinger named Red Hardigan (Clint Eastwood). He asks Bret to stay for a while and help break them up. Not really wanting to get involved, Bret changes his tune when he’s offered $1,000 to hang around for a week. There is one serious problem, though, and that’s the fact that Red has a reputation for being extremely fast and accurate with a gun, and he’s not afraid to use it. When Bret actually sees a demonstration of Red’s shooting skills, he knows he’s going to have to come up with a plan to drive Red away that avoids a gunfight at all costs. And that’s exactly what he does. I won’t give away exactly what he does, but it involves his brother Bart (Jack Kelly) and a notorious gunslinger named John Wesley Hardin, and it’s genius!

As we continue to celebrate the birthday of Hollywood legend Clint Eastwood, I decided I’d watch his 1959 guest starring appearance on the TV series MAVERICK with James Garner. I recently watched Eastwood and Garner work together in the enjoyable “geezers in space” movie SPACE COWBOYS (2000), which came out about 40 years after this. With that fresh in mind, I especially enjoyed seeing them work together while they were both in their prime. “Duel at Sundown” is the first episode I’ve watched of the MAVERICK TV series, and I must say that I had a ball with it. James Garner’s effortless charisma and laid back demeanor as Bret Maverick make his character right down my alley. Nothing seems to rattle the man, and he’s as funny as hell! As of the time of this review, all five seasons of the series are streaming on PlutoTV, so I’m planning on catching some more episodes as I can. As far as the young Clint Eastwood, who was 29 when this show premiered, he definitely looks the part of a future star. Maybe I’m just being influenced by what he’s accomplished over the last 60 years, but his steely intensity, his great head of hair, and his way with the ladies are all on display. And even though his character of Red is a hot headed gunslinger who’s driven by jealousy, there are a couple of times when he flashes that million dollar smile, and you can’t help but like him. For me, it’s fun to watch these megastars in roles when they were just working actors trying to build a career. You can usually see the qualities that will make them the most popular actors in the world, but they’re still going to lose to the star of the series at the end. It’s a rite of passage.

Overall, “Duel at Sundown” is an excellent introduction to the MAVERICK TV series for me. It’s funny and actually quite clever, as evidenced by the scheme that Bret Maverick comes up with at the end to keep from having to face Red in a gunfight. But the true highlight is seeing Garner, in one of his signature roles, working with a young Eastwood who’s destined for stardom. I highly recommend it!

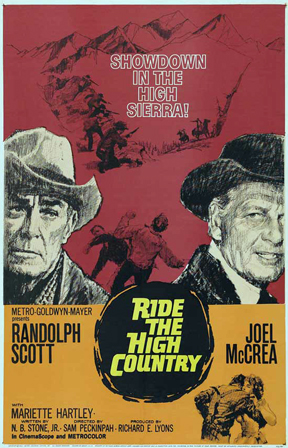

It’s the turn of the 20th century and the Old West is fading into legend. When they were younger, Steve Judd (Joel McCrea) and Gil Westrum (Randolph Scott) were tough and respect lawmen but now, time has passed them by. Judd now provides security for shady mining companies while Gil performs at county fairs under the name The Oregon Kid. When Judd is hired to guard a shipment of gold, he enlists his former partner, Gil, to help. Gil brings along his current protegé, Heck Longtree (Ron Starr).

It’s the turn of the 20th century and the Old West is fading into legend. When they were younger, Steve Judd (Joel McCrea) and Gil Westrum (Randolph Scott) were tough and respect lawmen but now, time has passed them by. Judd now provides security for shady mining companies while Gil performs at county fairs under the name The Oregon Kid. When Judd is hired to guard a shipment of gold, he enlists his former partner, Gil, to help. Gil brings along his current protegé, Heck Longtree (Ron Starr).