“Bloodlust is our birthright!” — Bobby Thompson

Edgar Wright’s 2025 take on The Running Man is an adrenaline shot to the chest and a sly riff on our era’s obsession with dystopian game shows, all filtered through his own eye for spectacle and pacing. Unlike many of his earlier works, such as Shaun of the Dead and Scott Pilgrim vs. The World, which bristle with meta-commentary, the film is a sleeker and more bruising affair. At its core, this is a survival thriller decked out in neon, driven by a director who wants to both honor and outpace what’s come before.

Wright’s version ditches the muscle-bound caricature of the 1987 Schwarzenegger adaptation, recentering on a more grounded protagonist. Glen Powell’s Ben Richards isn’t a quip-dispensing tank; he’s a desperate father, pressed to extremes, haunted more by anxiety than rage. We meet him in a world where reality TV devours everything, and nothing is too cruel if it wins the ratings war. Richards is cast as the sacrificial everyman, volunteering for the deadly Running Man show only because his family’s survival is at stake, not his ego. This lends the film a more human—and frankly, more believable—edge than either of its predecessors.

Visually, The Running Man is vintage Wright: kinetic and muscular, with chase scenes propelled by propulsive synths and punchy editing, each set piece designed as much to thrill as to disorient. Gone, however, is much of the director’s comedic ribbing; what remains is a tense visual feast, saturated in electric colors and relentless motion. The camera rarely settles. The television show itself is depicted as both garish and sinister, a spectacle that feels plausible because it’s only five minutes into our own future.

The film takes sharp aim at the machinery of television and the spectacle it creates, exposing how entertainment can thrive on cruelty and manipulation. It highlights a world where reality is heavily curated and shaped to serve ratings and control, with the audience complicit in consuming and encouraging the degradation of genuine human experience. The media in the film mirrors warnings that have circulated in recent years—that it has become a tool designed to appease the masses, even going so far as to use deepfakes to manipulate narratives in favor of particular agendas. While this focus on broadcast media delivers potent social commentary, Wright does drop the ball a bit by concentrating too much on traditional TV media at a time when entertainment consumption is largely online and more fragmented. This narrower scope misses an opportunity to deeply engage with the digital age’s sprawling and insidious impact on public attention and truth.

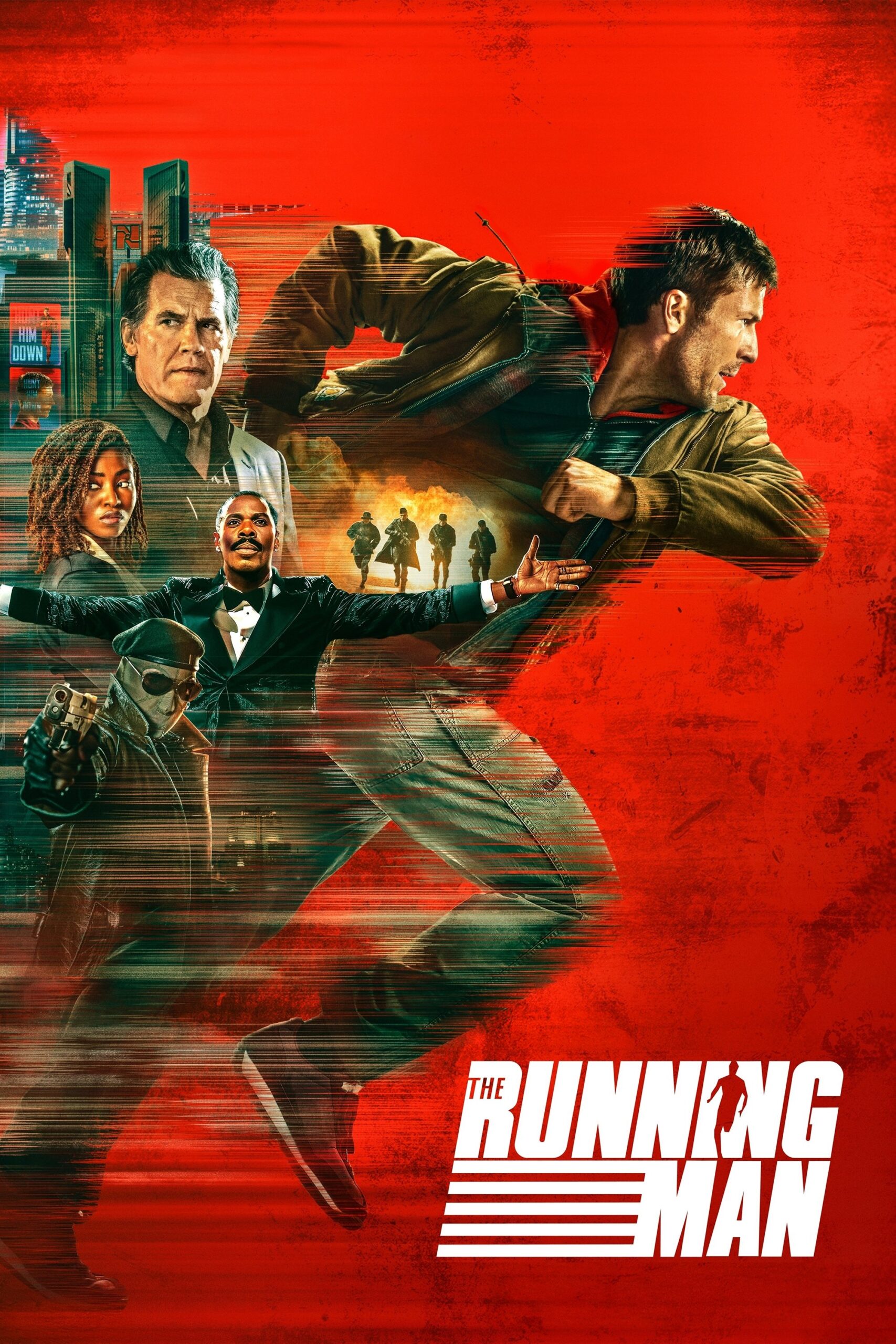

Glen Powell’s performance is pivotal to the film’s success. He anchors the story, selling both the exhaustion and the resolve required for the role. This Ben Richards is no superhero—his fear feels palpable, and his reactions are messy, urgent, and often impulsive. Opposite him, Josh Brolin steps in as Dan Killian, the show’s orchestrator. Brolin’s performance, smooth and menacing, turns every negotiation and threat into a master class in corporate evil. The stalkers, the show’s gladiatorial killers, are less cartoon than their 1987 counterparts, but all the more chilling for their believability—branding themselves like influencers, they embody a world where violence and popularity are inseparable.

On the surface, Wright’s Running Man leans heavily into social satire. It lobs grenades at infotainment, the exploitation inherent in reality TV, and the way audiences are silently implicated in all the carnage they consume. Reality is a construct, truth is whatever the network decides to show, and every moment of suffering is a data point in an endless quest for engagement. The critique is loud, though not always nuanced. Where Wright has previously reveled in self-aware storytelling, here he pulls back, focusing on the mechanics and cost of spectacle more than its digital afterlife.

Action is where the film hits hardest. Wright brings his expected flair for movement and tension, with chase sequences escalating to wild, blood-smeared crescendos, and hand-to-hand fights that feel tactile rather than stylized. The film borrows more heavily from the structure of King’s novel, raising stakes with each new adversary and refusing to let viewers catch their breath. Despite the non-stop pace, the movie runs a little too long—some sequences feel indulgent, and the final act’s rhythm stutters as it builds toward its conclusion. Still, even in its bloat, there’s always something energetic or visually inventive happening onscreen.

The movie’s climax and resolution avoid over-explaining or revealing too much, instead choosing to leave room for interpretation and suspense about the outcomes for the characters and the world they inhabit. This restraint preserves the tension and leaves viewers with something to chew on beyond the final credits.

For fans of Edgar Wright, there’s a sense of something both familiar and altered here. The visual wit, the muscular editing, the stylish sound cues—they’re all present. Yet the film feels less like a playground for Wright’s usual whimsy and more like a taut, collaborative blockbuster. It’s playfully brutal and thoroughly engaging, but does not, in the end, subvert the genre quite as gleefully as some might hope. For every moment of subtext or clever visual flourish, there is another in which the movie simply barrels forward, content to dazzle and provoke in equal measure.

The Running Man (2025) is a film with a target audience—those who want action, smart but accessible social commentary, and just enough character work to feel the stakes. It will delight viewers drawn to a flashier, meaner take on dystopian spectacle, and Powell’s central performance is likely to win over skeptics and fans alike. If you’re hoping for a thesis on algorithmic age or a meditation on surveillance capitalism, you may need to look elsewhere. But if you want a turbo-charged chase movie that occasionally stops to wag a finger at the world that spawned it, you’re likely to have a great time.

Ultimately, Edgar Wright’s Running Man is a sharp, glossy refit of a classic dystopian story, packed with high-octane action and grounded by its central performance. It won’t please everyone and doesn’t attempt to, but it never forgets that, above all, good television keeps us running. In the era of spectacle, that might be all you need.