“We will not sterilize every Jew and wait for them to die. We will not sterilize every Jew and then exterminate the race. That’s farcical.” — Reinhardt Heydrich

HBO’s Conspiracy (2001) masterfully dramatizes the infamous Wannsee Conference, held on January 20, 1942, where high-ranking Nazi officials orchestrated the Final Solution. The film’s running time mirrors the historical meeting itself, distilling one of the darkest moments in history into a single, chilling sitting that balances historical fidelity, psychological insight, and dramatic restraint. The premise is stark and deceptively simple: a group of men, most of whom had never previously met, gather in a sun-drenched villa outside Berlin to discuss systematic mass murder while enjoying fine food and polite conversation. This contrasting setting, rendered with careful attention to period detail, powerfully underscores what Hannah Arendt called the “banality of evil.” In Conspiracy, evil is not the property of villainous caricatures, but of functionaries and technocrats—chillingly rational and disturbingly mundane.

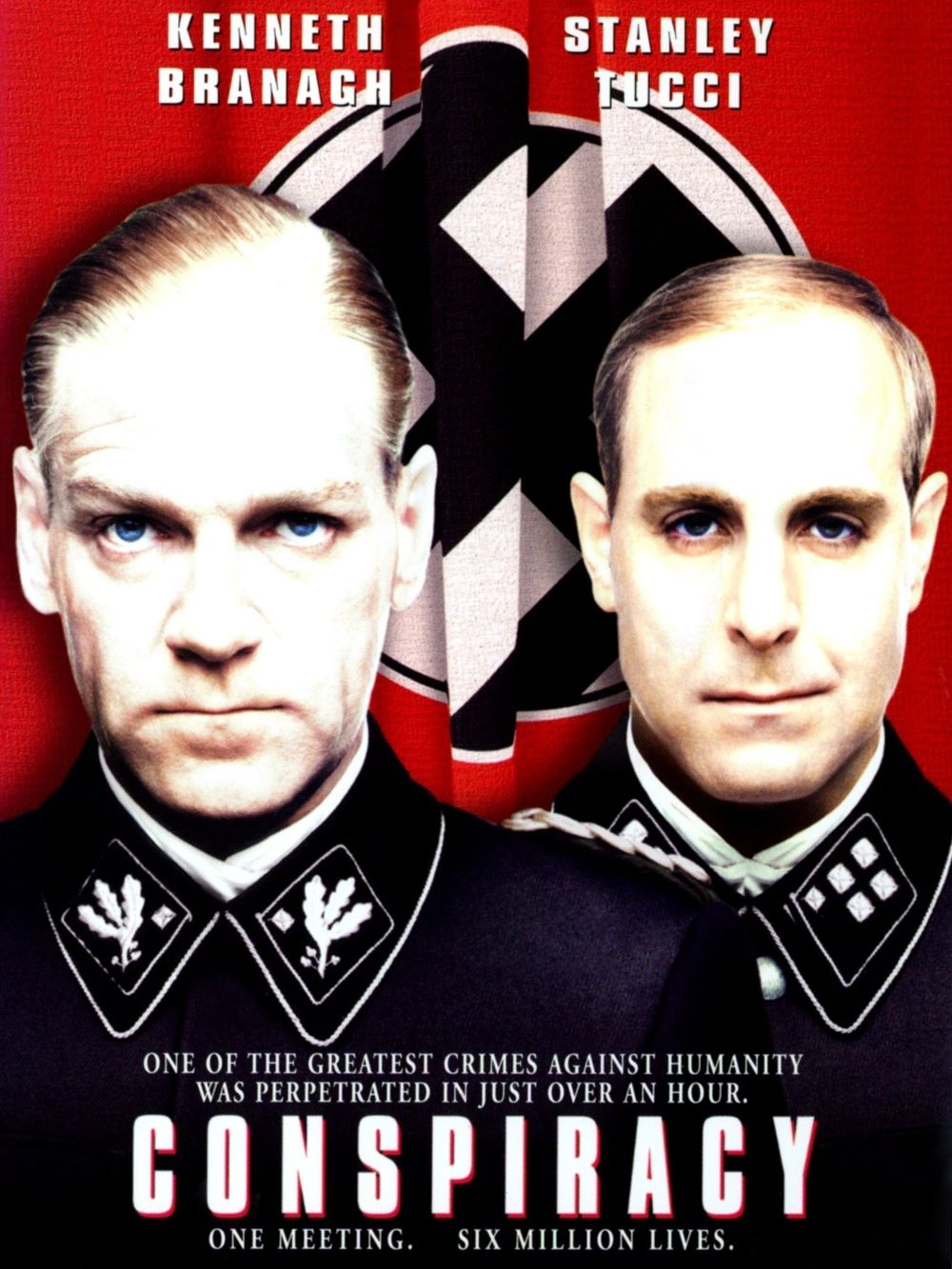

Much of the film unfolds in real time, utilizing dialogue taken from the sole surviving minutes of the Wannsee Conference. Screenwriter Loring Mandel and director Frank Pierson avoid unnecessary embellishments, allowing the facts and the conversations themselves to carry the full, horrifying weight. Kenneth Branagh gives an Emmy-winning performance as Reinhard Heydrich, the orchestrator and presiding presence at the conference. Branagh’s portrayal is both urbane and authoritative, presenting Heydrich as a figure whose affable composure thinly veils his unwavering commitment to genocide. There is no soaring rhetoric or overt menace; Heydrich’s evil is presented with administrative casualness, making it all the more chilling.

Stanley Tucci is equally compelling as Adolf Eichmann, Heydrich’s logistical right hand and the architect of the machinery of death. Tucci infuses Eichmann with a quiet efficiency and bureaucratic pride—a portrait of a man more attached to process than morality, disturbingly bland in his demeanor. The supporting cast is no less impressive. Colin Firth, as Dr. Wilhelm Stuckart, portrays a legal architect of Nazi race law who appears increasingly unsettled as the agenda shifts from disenfranchisement to extermination. Each attendee is rendered with psychological nuance. Some are disturbingly enthusiastic about their roles, while others are quietly apprehensive, yet ultimately complicit. These subtle gradations of doubt, ambition, and opportunism animate the film’s psychological landscape.

The dialogue, rooted in the actual transcript and skillful dramatic writing, eschews melodrama. The horror emerges not through spectacle, but in analytic exchanges about logistics, quotas, and definitions—the cold calculus of genocide. The men’s debates around how to classify mixed-race Jews, whether sterilization is preferable to extermination, and who should be spared create a bureaucratic puzzle as vile as its intent. Their discussions are delivered in a neutral, even mundane tone, which heightens the chilling reality of what they are planning. Pierson’s direction is restrained; the film never leaves its confined setting, emphasizing the claustrophobic mood of collective complicity. The camera lingers on faces rather than violence, building tension through small gestures—a glance, a pause, the clinking of glassware. The impact of what is said is matched only by the weight of what goes unsaid, until Heydrich, in a quietly devastating moment, makes the true purpose explicit.

More than a simple history lesson, Conspiracy meditates on themes of collective guilt, moral responsibility, and the terrifying ease with which ordinary people become accessories to atrocity. The film is haunted by bureaucracy; if everyone is “just following orders” or “simply doing their job,” the boundaries of blame blur and diffuse. The characters’ debates skillfully skirt the language of murder, favoring euphemisms such as “evacuation” or “resettlement.” This allows viewers to witness, in real time, the kind of moral erosion that enables atrocity on a massive scale. The dry, matter-of-fact tone of the film deepens its emotional impact, forcing the audience to comprehend that such horrors were conjured not in a frenzy, but in calm administrative exchanges over lunch.

For both historians and general audiences, Conspiracy earns praise for its meticulous adherence to historical detail. The screenplay closely follows the Wannsee minutes, and the film’s design choices—muted score, period-accurate costumes, and careful pacing—all serve to render bureaucratic evil as mundane and unremarkable. This unwavering restraint, however, does impose certain limits. The film’s dramatic arc is inherently subdued; the absence of conventional action or narrative tension makes it unfold like an extended negotiation rather than a traditional drama. Some viewers may find this lack of overt conflict stifling or static, resulting in a work that feels more “important” than “entertaining,” but this is clearly by design.

Conspiracy received widespread acclaim for both its historical gravity and psychological depth. Branagh and Tucci, in particular, were celebrated for their nuanced performances. The film is often cited as a model example of how the “banality of evil” operates—not through monsters, but through functionaries in tailored uniforms, sipping wine and rationalizing extermination. For those unfamiliar with the events, the manner in which these men discuss matters of life and death with casual detachment is shocking. As one critic noted, “Most people believe they know what evil looks like… But in Conspiracy, men of true evil met in pristine, gorgeous surroundings… and go about their business leisurely… with a smile and barely a hint of remorse.”

Within the canon of Holocaust cinema, Conspiracy stands apart from films like Schindler’s List or The Pianist, which focus on the suffering and survival of victims. Instead, it occupies a space similar to Downfall and the earlier Die Wannseekonferenz, dramatizing not the machinery of genocide but the mindsets of its architects. By confining itself to dialogue and implication, the film compels viewers to reflect on how civilization’s facades both enable and obscure horror.

The film’s lingering effect is not found in dramatic catharsis or tears, but in an enduring sense of discomfort. Conspiracy dramatizes not just a choice among evil options, but the ease with which those choices become rote procedure and social negotiation. The silence in the final act, as the men calmly disperse after codifying genocide, lands with a cold, almost procedural finality. The closing captions, briefly summarizing the fates of those present, deliver a sobering message: accountability was sporadic, often delayed, and never guaranteed.

Conspiracy is not casual entertainment, nor is it meant to be. Instead, it is essential viewing for anyone interested in the psychology of atrocity, the peril of bureaucratic amorality, and the enduring question of how ordinary people become complicit in extraordinary evil. With a screenplay of surgical precision, outstanding ensemble cast (especially Branagh and Tucci), and a director committed to understatement, HBO’s film demonstrates how history’s darkest decisions are forged not in chaos, but in chilling consensus. To those seeking to understand not only what happened at Wannsee, but how, Conspiracy offers an unblinking and quietly devastating answer.