Hey hey!! Before you read this, know that this isn’t the only review for The Longest Day. Lisa Marie also wrote about it. Read that first, and then double back here if you like.

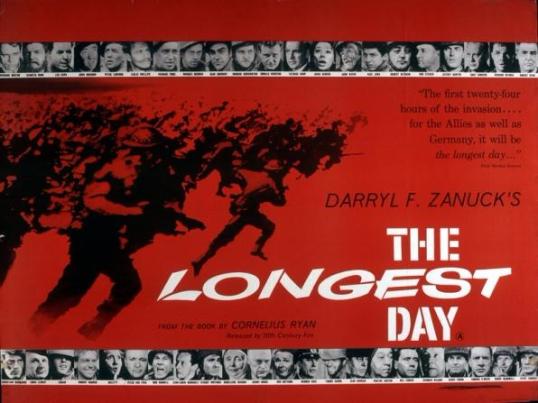

With June 6th being the 81st Anniversary of D-Day, I decided to write about 1962’s The Longest Day, a film often discussed in my family, but surprisingly, I don’t recall ever fully watching it until today. I’ll try to get a hold of a hard copy of this in the future. The film is currently available to watch (with ads) on YouTube. This was a film my Aunt adored, as she liked seeing the Military come to the rescue in any situation (which happened often in most classic sci-fi films). This, They Died With Their Boots On, and All Quiet on the Western Front were films she raved about.

According to the National WWII Museum, “The Allies suffered over 10,300 total casualties (killed, wounded, or missing), of which approximately 2,400 were on Omaha Beach.” it was also an incredible offensive achievement, with nations gathering together to take the fight to a common enemy.

I don’t have a whole lot to say about this. As this is a film based on actual events (which takes some movie related liberties), I can’t complain or state I loved the “story”. As my boss at my Dayjob sometimes says, “It is what it is.” In terms of presentation, however, I highly recommend it. The film never really falters, nor does it give you too much time to relax. There’s a quiet tension with all of the characters you meet (all of the Allied ones, anyway), wondering if they may make it through by the end. If nothing else, watching it reminds one of the sacrifices made and the courage of anyone deciding to run head first into battle like that.

The film is epic in scope, with a runtime of 3 hours and an all star cast that includes Robert Mitchum (Cape Fear), Eddie Albert (Dreamscape), John Wayne (The Quiet Man), Henry Fonda (Once Upon a Time in the West) Curt Jurgens (The Spy Who Loved Me), Red Buttons and Roddy McDowall (who would later work together in The Poseidon Adventure), Richard Beymer (West Side Story), Frank Findlay (Lifeforce), Gert Frobe and Sean Connery (both two years shy of working together in Goldfinger), Richard Burton (Cleopatra) and Robert Ryan (The Wild Bunch) among others.

Much like 1970’s Tora!Tora!Tora! (which my Dad often talked about), there were multiple directors for The Longest Day. Bernhard Wiki captured the German scenes, Andrew Marton handled the American ones, and Ken Annakin handled both the English and French sequences. This is all brought together in a seamless and pretty amazing tapestry. Unlike Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan, The Longest Day only covers the time leading up to and through the Omaha Beach assault, using the bulk of the film’s 3rd hour for the event. The entire film makes wonderful use of the time with all the alternate views, and by the time the first combat starts near the start of the 2nd hour, it continues to flow from interaction to interaction. There are also some wonderful arial shots over the battles, including an classic one shot that’s pretty marvelous given the time period.

The film takes place just before the invasion. American troops are already in the water on boats. Others are ready to parachute in. The French are ready to fight, waiting for the right phrase to hit the radio to put them into action. all are waiting to hear from the Britians on when the Allied Assault should begin. The weather isn’t optimal, but with the operation already delayed once before, President Eisenhower (Henry Grace) decides the 6th is the drop date. The Germans assume nothing will happen assaults are supposedly not done in harsh weather, but this proves to be quite the mistake.

It was wonderful to see everything come together. From the French sabotaging communications, to the strange comedy of soldier toting bagpipes to lead the Scottish into battle, or the Nuns who walked right through battle to save lives, it’s quite a sight to behold.