Audrey Hepburn and her Oscar. At least the Academy didn’t snub her!

Continuing our look at the Oscar snubs of the past, it’s now time to enter the 50s!

World War II was over. Eisenhower was President. Everyone was worried about communist spies. And the Hollywood studios still reigned supreme, even while actors like Marlon Brando and James Dean challenged the establishment. There were a lot great film released in the 50s. There were also some glaring snubs on the part of the Academy. Here’s twelve of them.

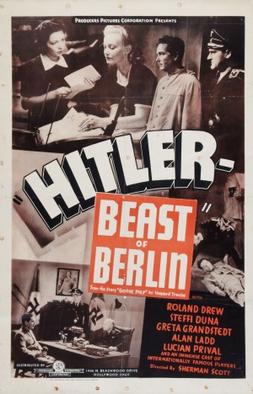

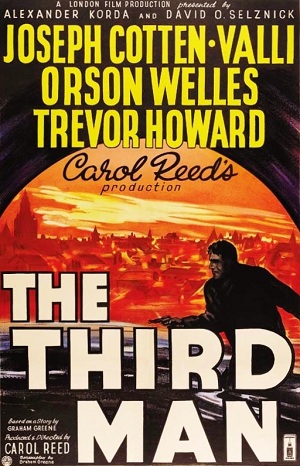

1950: The Third Man Is Not Nominated For Best Picture

….and Orson Welles was not nominated for Best Supporting Actor! The Third Man received three Oscar nominations, for Director, Cinematography, and Editing. The fact that Welles, Joseph Cotten, Alida Valli, and the film’s score were not nominated (and that King Solomon’s Mines was nominated for Best Picture instead of The Third Man) remains one of the more surprising snubs in Oscar history.

1952: Singin’ In The Rain Is Not Nominated For Best Picture

What the Heck, Academy!? This was the year that The Greatest Show On Earth won the Best Picture Oscar. Personally, I don’t think The Greatest Show On Earth is as bad as its reputation but still, Singin’ In The Rain is a hundred times better.

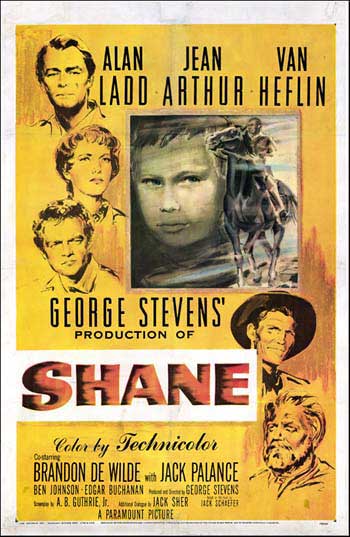

1953: Alan Ladd Is Not Nominated For Best Actor For Shane

How could Shane score a nomination for Best Picture without Shane himself receiving a nomination?

1954: Rear Window Is Not Nominated For Best Picture

Rear Window was not totally ignored by the Academy. Alfred Hitchcock received a nomination for directing. It also received nominations for Best Adapted Screenplay, Cinematography, and Sound. However, Rear Window was not nominated for Best Picture and James Stewart, Grace Kelly, Raymond Burr, and Thelma Ritter all went unnominated as well. Today, Rear Window is definitely better-remembered than the majority of 1954’s Best Picture nominees. Certainly, it deserved a nomination more than Seven Brides For Seven Brothers and Three Coins in The Fountain.

1955: Ralph Meeker Is Not Nominated For Best Actor For Kiss Me Deadly

I guess I shouldn’t be surprised. If the Academy wasn’t going to nominate Rear Window for Best Picture, there was no way that they would have nominated Ralph Meeker for playing a sociopathic private detective who, even if inadvetedly, helps to bring about the end of the world.

1955: Rebel Without A Cause Is Not Nominated For Best Picture or Best Actor

The 1955 Best Picture lineup was a remarkably weak one. The eventual winner was Marty, a likeable film that never quite escapes its TV roots. Picnic has that great dance scene but is otherwise flawed. Mister Roberts was overlong. Love Is A Many-Splendored Thing and The Rose Tattoo are really only remembered by those of us who have occasionally come across them on TCM. Perhaps the best-remembered film of 1955, Rebel Without A Cause, received quite a few nominations but it was not nominated for Best Picture. And while the Rebel himself, James Dean, was nominated for Best Actor, it was for his performance in East of Eden. 1955 was a strange year.

1955: Robert Mitchum Is Not Nominated For Best Actor For The Night of the Hunter

Robert Mitchum only received one Oscar nomination over the course of his entire career, for 1945’s The Story of G.I. Joe. He deserved several more. His performance as the villainous preacher in The Night of Hunter made Reverend Harry Powell into one of the most iconic film characters of all time.

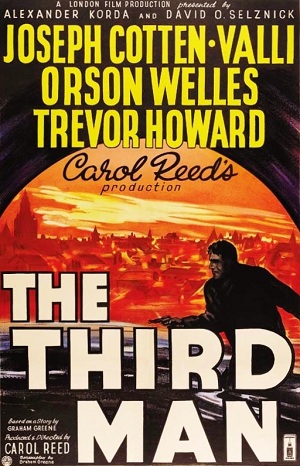

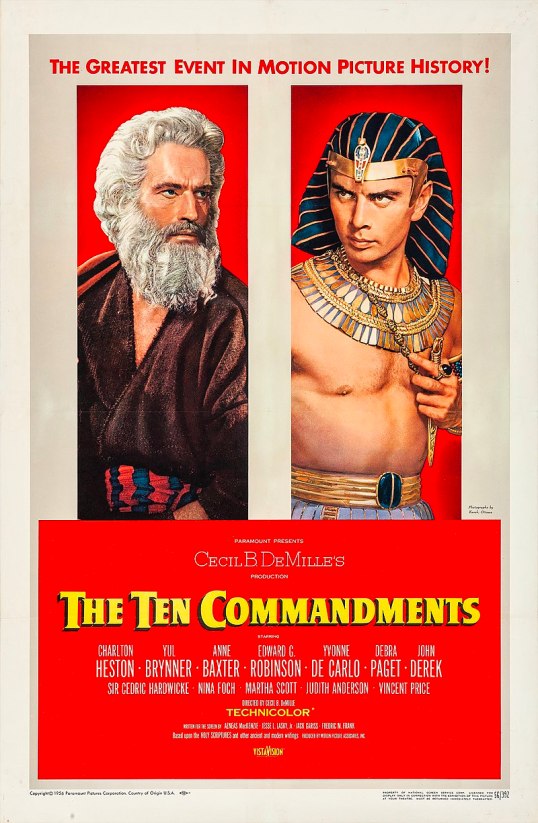

1956: Cecil B. DeMille Is Not Nominated For Best Director For The Ten Commandments

Cecil B. DeMille was only nominated once for Best Director, for 1952’s The Greatest Show On Earth. DeMille, however, deserved to be nominated for The Ten Commandments. As campy as DeMille’s films can seem today, he was an expert storyteller and that’s certainly evident when one watches The Ten Commandments, a film that holds the viewer’s attention for nearly four hours. DeMille deserved a nomination for the Angel of Death scene alone. The screams in the night are haunting.

1957: Henry Fonda Is Not Nominated For Best Actor For 12 Angry Men

With 12 Angry Men, Fonda did something that very few actors can. He made human decency compelling. One gets the feeling that, much like Tom Hanks in Captain Phillips, Fonda made it look so easy that the Academy took him for granted.

1958: Touch Of Evil Is Totally Ignored

Anyone who had researched the history of the Academy knows that there was no way that the 1950s membership would have ever honored Orson Welles’s pulp masterpiece, Touch of Evil. That said, it still would have been nice if they had. Touch of Evil has certainly go on to have a greater legacy than Gigi, the film that won Best Picture that year.

1958: Vertigo Is Almost Totally Ignored

Vertigo did receive nominations for Art Direction and Sound but Alfred Hitchcock, James Stewart, and the film itself were snubbed.

1959: Some Like It Hot Is Not Nominated For Best Picture or Best Actress

Some Like It Hot received 6 Oscar nominations, including nominations for Best Director, Best Actor, and Best Adapted Screenplay. It did not receive a nomination for Best Picture and, sadly, Marilyn Monroe did not receive a nomination for Best Actress. Much as with Henry Fonda in 12 Angry Men, one gets the feeling that the Academy took Monroe for granted. It’s sad to realize that, while two actresses have been nominated for playing Marilyn Monroe, Monroe herself would never be nominated.

Agree? Disagree? Do you have an Oscar snub that you think is even worse than the 12 listed here? Let us know in the comments!

Up next: Things get wild with the 6os!

Night of the Hunter (United Artists 1955; D: Charles Laughton)