The Strong, an educational institution in Rochester specializing in the study of games, announced the six inaugural inductees of their World Video Game Hall of Fame yesterday. So what? Well, it made its way onto a lot of major news sites, which means it is probably going to resurface again next year and, in time, become the closest we’ve got to an “official” Hall of Fame.

My gut reaction was “my what a pretentious title”, because the “World” VG HoF looks incredibly U.S.-centric. Their game history timeline pretty much completely ignores the fact that the U.S. did not control the international gaming market for the vast majority of the 20th century. I mean, this timeline is crazy. 1982, the year that the bloody Commodore 64 was released, they feature Chicago-based Midway’s Tron instead. 1986, the year that Dragon Quest set the standard for the next two decades of role-playing games, they are at such a loss to find anything novel that they dig up Reader Rabbit by Boston-based developers The Learning Company. In spite of devoting 1992 to Las Vegas-based Westwood Studios’ Dune II, LA-based Blizzard Entertainment steals 1994 with Warcraft: Orcs and Humans. Does the invention of RTS gaming really deserve two years? Well, it’s not like it was competing with the release of the Sony Playstation or anything. Oh that’s alright, we’ll feature it in 1995, since that’s when it came to America. This list also devotes 1993 to the development of the ESRB rating system (which only applies in America), 1996 to Lara Croft’s tits (seriously, does anyone actually give a shit about Tomb Raider?), and 2002 to the U.S. Army, because uh, freedom!

So yeah, World Video Game Hall of Fame my ass. But that doesn’t mean they got the first six wrong:

Pong (1972)

“Ladies and gentlemen, you have been hand selected to choose the five games which will accompany Pong into the Hall of Fame.” It had to go something like that. Pong invented gaming like Al Gore invented the internet. Could you imagine a Hall of Fame without Pong? I mean, it’s Pong! Really though, wasn’t computer gaming kind of inevitable? Was it the first game? Nope. Did it stand the test of time? Not really. Did it usher in the age of arcade gaming? I guess it did, but the game itself had little to do with that. It was a novelty. Replace it with anything else, and that other game would be just as famous, regardless of its content. I don’t like that. There is a reason why Pong is the only game of the six Hall of Famers that I never played as a kid or else upon release, and that has nothing to do with my age. I think we get hung up on its simplicity, its catchy name, this idea that it all began with two paddles and a ball, and the desire to point to something and say “this started it all”. Pong deserves recognition in any gaming hall of fame eventually, but top 6? We can do better.

NMY gives this selection a 5/10

Pac-Man (1980)

What are Pac-Man‘s claims to fame? Well, it was the first video game to be a major social phenomenon, generating a huge market for spin-offs, toys, animated cartoons, and all sorts of other consumer products. It was the first video game with a really memorable theme song. It remains the best-selling arcade game of all time. It generated a chart-topping shitty pop song. It even destroyed the gaming industry. (E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial has absolutely nothing on the devastating consequences of Pac-Man‘s abysmal Atari port.) And sure, it’s pretty boring, but it still lasted well into the 90s. I had a pirated DOS copy as a kid. Do you think anyone bothered to pirate Pong? Uh, no.

NMY gives this selection a 10/10

Tetris (1984)

Tetris is a game that we all agree to love because it is Russian, and like Russia, it is really evil and kind of a dick. Four Z blocks in a row? Really? I didn’t double tap that button. Go back! Ugh…. Tetris annoyed the hell out of me as a kid, but I certainly did play it. It also spawned a ton of cheap rip-offs, novel improvements, and largely unrelated block puzzle games that stole its name for publicity, and a lot of these vastly outclassed the original. If I look back on all the fun I had playing Tetris Attack for the Super Nintendo, or hosting TetriNET tournaments online in the late 90s, or the amount of time my wife wastes on Candy Crush Saga, it is hard for me to pretend that Tetris was not significant. It was the mother of all “endless puzzle” games, and it deserves credit for that, even if I hated the original Alexey Pajitnov Tetris, with its never-ending tiers of frustration.

NMY gives this selection a 9/10

Super Mario Bros (1985)

This is the real shoe-in. Nintendo was able to turn Mario into (I am assuming) the most recognizable fictional character in the world because the original Super Mario Bros was so great. A game released in 1985 is not supposed to still be this much fun 30 years later, but from novel settings and mechanics to outstanding control, this game ran the gamut of what a great side-scroller was supposed to be. This, at a time when there was very little in the way of quality competition to take inspiration from. The game’s lasting legacy is so pervasive in our culture that I would feel silly even bothering to summarize it.

NMY gives this selection a 10/10

Doom (1993)

“Why an FPS, World Video Game Hall of Fame?” Because “it also pioneered key aspects of game design and distribution that have become industry standards“, according to the official induction explanation. Design-wise, they laud it for “a game ‘engine’ that separated the game’s basic functions from other aspects such as artwork.” That might be an interesting point. I don’t know much about it, though I have to imagine that anything Doom did, Wolfenstein 3D did first. Distribution-wise, they talk about how id Software marketed downloadable expansions and encouraged multi-player, online gaming. That point fails to impress me. Doom launched in 1993, which means no games before it really had the option to market themselves in this way. “First” only counts for me if the move is innovative, not inevitable. So we are left with some sort of novel modular processing system and the fact that it was the first really successful FPS. Those are fine points. I might not like FPS games, but I can’t deny that they have had a more lasting impact than say, fighting or sports games. Placing so much weight on the play style does, however, open up the doors for a lot of why nots. Why not Diablo? Why not Dragon Quest? Why not Command & Conquer?

NMY gives this selection a 7/10

World of Warcraft (2004)

I am not entirely sure why the World Video Game Hall of Fame chose World of Warcraft, because they aren’t telling. Their write-up goes into detail on what makes MMORPGs so revolutionary, but none of it is really unique to WoW. They throw out some numbers about WoW’s player base and monthly profit, and then bam, inaugural hall of fame induction. I am probably the last person to give an accurate assessment of how World of Warcraft changed gaming, because I still actively play it, but I have to believe that its enormous popularity had a lot to do with its place in time. Coming in to the 21st century, we all knew someone who played EverQuest, and we all (all of us, right guys?) secretly wanted to abandon our real lives and nerd out in 24/7 multiplayer fantasy immersion. I never played EverQuest, however, or Final Fantasy XI for that matter, because I still had dial-up internet. World of Warcraft launched right around the time that the majority of gamers were becoming equipped to play something of its magnitude. That being said, WoW is going on 11 years now, and still going strong. I’ve never seriously considered canceling my subscription. Blizzard landed on a market ripe for the picking, but they have carefully cultivated it ever since.

NMY gives this selection an 8/10

Over all, I think the World Video Game Hall of Fame is off to a good start. Pong is the only inaugural entry I strongly disagree with, but were it missing, would people still take the organization seriously? Doom is a bit sketchy to me, because its only claim seems to be “first popular FPS”. I think GoldenEye 007 was the game to push FPS into the mainstream and really reach beyond the genre, while Blizzard clearly dominated online gaming with Diablo and Starcraft, whatever id Software happened to do “first”. Doom is a good candidate, no doubt, but I feel like it belongs in another class. It would have fit in more nicely in a 2016 school that pushed genre-standardizing games like Dragon Quest, The Legend of Zelda, Street Fighter II, and Space Invaders.

Is that what we have to look forward to in 2016? Well, based on the runners-up from 2015, maybe not. The list did include Space Invaders and The Legend of Zelda, along with worthy contenders Pokémon Red and Blue and The Oregon Trail. Beyond that, it got a bit dicey. It is hard to imagine that Angry Birds, for instance, almost made the top 6. Sonic the Hedgehog would be long forgotten if not marketed as Sega’s response to Mario, yet it was a contender. FIFA International Soccer was the only sports entry–an odd choice, given that I have never heard of it, it only came out in 1993, and Tecmo Super Bowl exists. The other options were Minecraft–a bit young yet, don’t you think?–and oddly, The Sims, which I am sure was quite fun to play and left no lasting impact on gaming whatsoever. Well, they’ve got another year to straighten things out.

Stand Alone Complex lies much closer to the root of my music series, because some of the key issues it tackles have since arisen online in the real world. Everyone is well familiar with the use of V for Vendetta-styled Guy Fawkes masks in protests originating from the internet, but there is a decent chance you have also caught a glimpse of an odd blue smiley face among the rabble. The Laughing Man image originates from Stand Alone Complex, where it functions as a mask employed anonymously by individuals taking public action independently of each other. At first, an advocate for social justice uses it to disguise himself while committing a ‘terrorist’ act, but the image quickly overreaches his motives. Others commit unrelated political sabotage under the guise. Corporations employ it to discredit their competitors. Pranksters use it as a sort of meme, forming the shape with chairs on a rooftop and cutting it into a field as a crop circle, for instance. The image has no concrete meaning, and everyone who uses it essentially ‘stands alone’, but the public perceive the Laughing Man as a single individual.

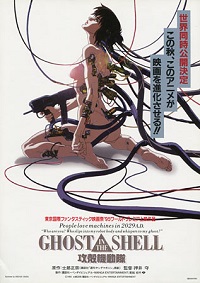

Stand Alone Complex lies much closer to the root of my music series, because some of the key issues it tackles have since arisen online in the real world. Everyone is well familiar with the use of V for Vendetta-styled Guy Fawkes masks in protests originating from the internet, but there is a decent chance you have also caught a glimpse of an odd blue smiley face among the rabble. The Laughing Man image originates from Stand Alone Complex, where it functions as a mask employed anonymously by individuals taking public action independently of each other. At first, an advocate for social justice uses it to disguise himself while committing a ‘terrorist’ act, but the image quickly overreaches his motives. Others commit unrelated political sabotage under the guise. Corporations employ it to discredit their competitors. Pranksters use it as a sort of meme, forming the shape with chairs on a rooftop and cutting it into a field as a crop circle, for instance. The image has no concrete meaning, and everyone who uses it essentially ‘stands alone’, but the public perceive the Laughing Man as a single individual. Ghost in the Shell has remained a uniquely relevant franchise in science fiction because it got so many ideas right. In 1989, at a time when internet was still a novelty of college libraries, the manga offered a world of total connectivity, where every human and device belonged to a global network. In 2002, Stand Alone Complex introduced the Laughing Man, and shortly afterwards the real world knew an equivalent. Whether this bodes well for the franchise’s dabblings into cyborg technology, only time can tell, but history has certainly made an inherently fascinating fictional world all the more compelling. In the Ghost in the Shell universe, science has fully bridged the gap between computers and neural systems, allowing electronic implants to directly convert wireless digital information into stimuli compatible with the senses. The average citizen possesses visual augmentations which allow them to directly browse the internet via voice command. More complex technology delves deeper, creating a sort of sixth sense whereby users can engage a network through thought command. Some individuals, especially accident victims with the means to afford it, might have their entire bodies replaced by neurally triggered machine components.

Ghost in the Shell has remained a uniquely relevant franchise in science fiction because it got so many ideas right. In 1989, at a time when internet was still a novelty of college libraries, the manga offered a world of total connectivity, where every human and device belonged to a global network. In 2002, Stand Alone Complex introduced the Laughing Man, and shortly afterwards the real world knew an equivalent. Whether this bodes well for the franchise’s dabblings into cyborg technology, only time can tell, but history has certainly made an inherently fascinating fictional world all the more compelling. In the Ghost in the Shell universe, science has fully bridged the gap between computers and neural systems, allowing electronic implants to directly convert wireless digital information into stimuli compatible with the senses. The average citizen possesses visual augmentations which allow them to directly browse the internet via voice command. More complex technology delves deeper, creating a sort of sixth sense whereby users can engage a network through thought command. Some individuals, especially accident victims with the means to afford it, might have their entire bodies replaced by neurally triggered machine components.