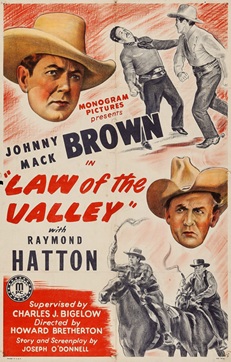

Dan Stanton (Edmund Cobb) and Condon (Tom Quinn) are planning to run a bunch of ranchers off their land by cutting off their water supply. Once the ranchers leave, Stanton and Condon will be able to sell their land to the railroads. After the bad guys murder a rancher named Jennings (George Morell), the rancher’s daughter (Lynne Carver) sends a message to U.S. Marshals Nevada Jack McKenzie (Johnny Mack Brown) and Sandy Hopkins (Raymond Hatton). Old friends of the murdered rancher, Sandy and Nevada come to town to rally the ranchers against Stanton and his men and to free up the water that’s been dammed up.

Dan Stanton (Edmund Cobb) and Condon (Tom Quinn) are planning to run a bunch of ranchers off their land by cutting off their water supply. Once the ranchers leave, Stanton and Condon will be able to sell their land to the railroads. After the bad guys murder a rancher named Jennings (George Morell), the rancher’s daughter (Lynne Carver) sends a message to U.S. Marshals Nevada Jack McKenzie (Johnny Mack Brown) and Sandy Hopkins (Raymond Hatton). Old friends of the murdered rancher, Sandy and Nevada come to town to rally the ranchers against Stanton and his men and to free up the water that’s been dammed up.

This was a pretty standard Johnny Mack Brown western. Johnny Mack Brown and Raymond Hatton always made for a good team but the story here is pretty predictable. After you watch enough B-westerns, you start to wonder if there were any made that weren’t about outlaws trying to run ranchers off their land. It’s interesting that these movies almost always center, in some way, around the coming of the railroad. The railroad is opening up the frontier and bringing America together but it also brings out the worst in the local miscreants.

As with a lot of B-westerns, the main pleasure comes from spotting the familiar faces in the cast. Charles King and Herman Hack play bad guys. Tex Driscoll plays a rancher. Horace B. Carpenter has a small role. These movies were made and remade with the same cast so often that that watching them feels like watching a repertory company trying out their greatest hits.