Stephen King’s writing style in “One for the Road” exemplifies his mastery of atmosphere, character voice, and narrative restraint. While much of his later work often invests heavily in world-building over long stretches, this short story demonstrates his ability to deliver a rich, immersive experience in a concise format. His choices here, both stylistic and structural, serve the story’s central purpose: to convey unspoken dread and the inevitability of evil.

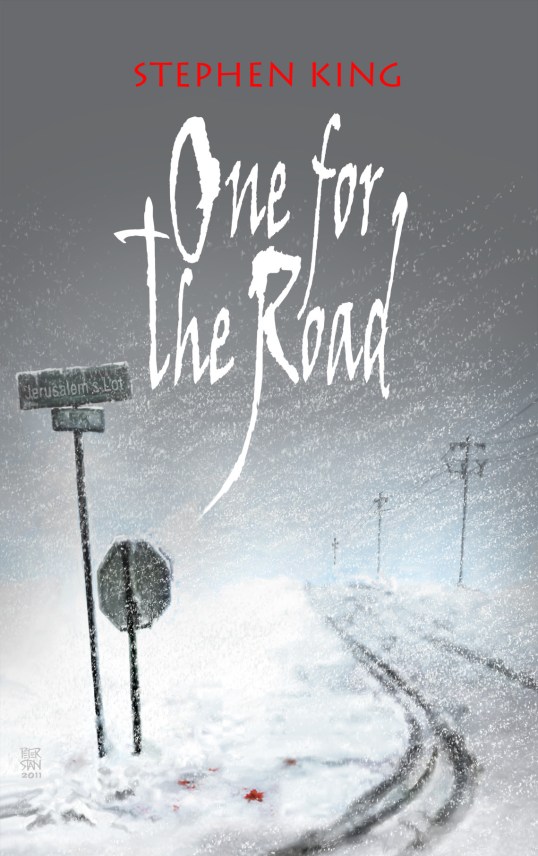

The story serves as a chilling epilogue to ’Salem’s Lot, set during a brutal New England winter many years after a fire destroyed the infamous town. Told by Booth, an elderly local from nearby Falmouth, it begins in the warm familiarity of Herb Tookey’s bar, where Booth and Herb are longstanding fixtures. Their evening is interrupted when Gerald Lumley, cold and near collapse, stumbles in. Lumley explains that his car broke down in the snow miles away, and that he left his wife and daughter in the vehicle while seeking help. Tension deepens when he reveals the breakdown happened near Jerusalem’s Lot—a place everyone in the area fears but rarely discusses. Despite knowing the dangers, Booth and Herb reluctantly agree to help him return.

Their journey into the storm is both physically taxing and emotionally tense, as the two locals understand all too well what they might find. As they approach the outskirts of The Lot, King uses sparse detail and implication to build dread. By the time they reach Lumley’s car, the supernatural horror makes itself known, hammering home the message that evil never truly dies—it lingers, waiting for an opportunity to strike.

King’s decision to frame “One for the Road” within a harsh New England winter is critical to its success. The cold itself becomes an antagonist—slowing movement, reducing visibility, and draining the characters’ strength—adding a physical urgency to the supernatural threat. Snowstorms are a recurring motif in his work (The Shining, Storm of the Century) because they isolate the characters, making escape impossible and forcing confrontation with whatever is lurking nearby. The blizzard in this story intensifies feelings of claustrophobia, despite the vastness of the open, rural landscape.

King also makes the setting deeply familiar for his readers. Falmouth feels like a lived-in place, with its bar, locals who know one another’s routines, and whispered legends about The Lot. The story doesn’t waste time describing Jerusalem’s Lot in detail; instead, its horrors exist in the margins, in what the locals refuse to say.

The choice of Booth as the first-person narrator adds authenticity and intimacy. Booth speaks with the cadence of an elder New Englander—practical, reserved, and hardened by experience. Readers never doubt that this is the account of someone who understands the local history and its dangers. The conversational delivery, sprinkled with regional colloquialisms, draws the reader into the moment rather than presenting a polished, detached recounting.

Rather than sensationalizing The Lot’s horrors, Booth lets them linger unsaid. King understands that withholding explicit details can fuel imagination more effectively than extravagant description. This restraint makes the story’s climax more impactful because the dread has been steadily fed through implication.

The story’s pacing is deliberate but tight. King introduces the danger early—Lumley’s car is stranded near Jerusalem’s Lot—then uses the journey back to extend suspense. The structure mirrors a descent into darkness: starting in the relative safety of Herb Tookey’s bar, venturing into the blizzard, and finally confronting the true horror at the edge of The Lot. King avoids unnecessary subplots, instead focusing on a single mission: rescuing Lumley’s family. This gives the narrative relentless forward motion while allowing tension to rise in small increments.

One of King’s most notable thematic choices is the portrayal of evil as a constant, indestructible force. In ’Salem’s Lot, that evil once emanated from the Marsten House, a decaying mansion that served as both the symbolic and literal heart of darkness. By the time of “One for the Road,” however, the Marsten House has been burned down and stripped of its power. Yet, rather than eradicating the evil, its essence has expanded outward—the town itself has inherited its malign influence. The Lot has effectively become the new Marsten House, and its ruined streets and frozen remains now radiate the same dark gravity that once resided solely within those walls. King transforms the geography of evil: what was once contained in a single haunted house has transposed itself over the entire landscape, infecting the air, the snow, and the silence with something sentient and waiting.

King also plays with the tension between duty and self-preservation. Booth and Herb could have ignored Lumley’s plea. Their choice to help—despite knowing what might await them—aligns with King’s recurring motif that true courage lies in facing evil with no guarantee of victory.

Even when weaving atmosphere, King exercises a tight control over detail. The bar scene is economical: we know just enough about Herb, Booth, and their friendship to trust their dynamic. The blizzard is described vividly but without purple prose. This brevity forces the reader to focus on what matters—the growing realization that Lumley’s family is in mortal danger. The vampires themselves receive minimal “screen time,” a deliberate choice that allows the prior suspense to make their eventual appearance all the more devastating.

As a companion piece, “One for the Road” functions as both a continuation and a tonal reinforcement of ’Salem’s Lot. Rather than tying up loose ends, King emphasizes that nothing was truly resolved. Evil is only temporarily held back, and the destruction of the town did not remove its blight. By telling the story through outsiders who skirt the edge of The Lot without entering deeply into it, King preserves the town’s mystique, forcing readers to imagine the horrors that remain—an imaginative space where dread thrives long after the last page.

Ryan C.'s Four Color Apocalypse

Michael (William Bumiller) owns the hottest health club in Los Angeles but that may not stay true if he can’t do something about all the guests dying. Members get baked alive in the sauna. Another is killed when a malfunctioning workout machine pulls back his arms and causes a rib to burst out of one side of his body. Shower tiles fly off the wall and panic a bunch of naked women. A woman loses her arm in a blender and a man is somehow killed by a frozen fish. Strangely, all of the deaths don’t seem to hurt business as people still keep coming to the gym. Surely, there are other, safer health clubs in Los Angeles.

Michael (William Bumiller) owns the hottest health club in Los Angeles but that may not stay true if he can’t do something about all the guests dying. Members get baked alive in the sauna. Another is killed when a malfunctioning workout machine pulls back his arms and causes a rib to burst out of one side of his body. Shower tiles fly off the wall and panic a bunch of naked women. A woman loses her arm in a blender and a man is somehow killed by a frozen fish. Strangely, all of the deaths don’t seem to hurt business as people still keep coming to the gym. Surely, there are other, safer health clubs in Los Angeles.