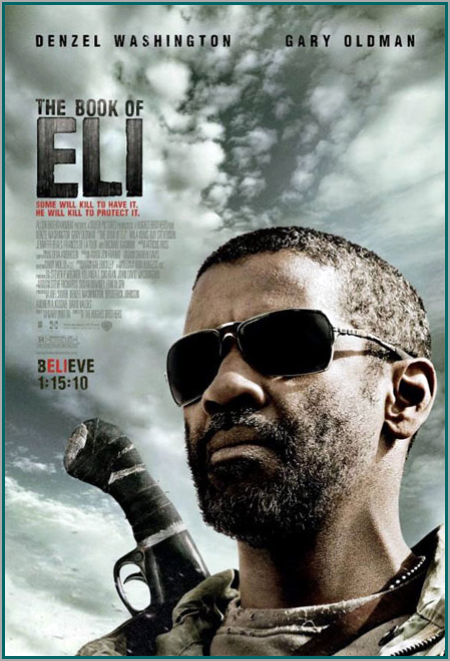

In 2001 the Hughes Brothers released their film adaptation of the celebrated and very dense graphic novel From Hell. A graphic novel meticulously researched and every detail reconstructed to tell the tale of Jack the Ripper and his killing spree in the London slum of Whitechapel during the turn of the 19th-century into the 20th. It was a film fans of the graphic novel have been waiting for years since it was initially announced. When it was finally released in 2001 the reception and reaction from both critics and audiences were a resounding thumbs down. The Hughes Brothers first major film outside of their comfort zone of the urban setting was seen as a colossal failure and for almost a decade they seemed to have put themselves into a self-imposed exile from Hollywood. It’s now 2010 and with a cas consisting of Denzel Washington and Gary Oldman on opposite sides it looks like the Hughes Brothers have returned from their exile with a very good post-apocalyptic Western called The Book of Eli.

I call The Book of Eli a post-apocalyptic Western because it’s what the film reminded me most of. The setting may be all ashen gray with the world and the environment decades into what the cast can only describe as “the flash” which ended everything. But with all that the film still felt like a throwback to the Westerns of Sergio Leone with equal parts Akira Kurosawa samurai epics. Taking cue from the screenplay by Gary Whitta, the Hughes Brothers set up the rules of the film from the very first frames. We see a world still raining ash even thirty years since a war (hinted as being caused and fought between the major religions of the world). It is a world where cats have become not just the source of food but also oil for chapped lips. If one bought into the world being presented in the very first ten minutes of the film then the rest the remaining hour and forty minutes would be easy going.

The very first twenty minutes of the film was pretty much free of dialogue as we see the No-Name walker (played by Denzel Washington) survive a day on the road inside an abandoned homestead with only an ancient iPod and the titular book to keep him company. When we finally hear his character speak it is in hushed tones, almost a whisper as if his time of wandering the blasted landscape in solitude has made speaking out loud something almost forgotten. In fact, throughout most of the film Denzel’s character rarely speaks and when he does it doesn’t bode well for those trying to keep him from the path he had been set on for the past thirty years since after “the flash.” It’s during these “encounters” when his character must protect himself that the Hughes Brothers show their unique style in how to film an action scene.

The action scenes owe much of their smooth, precise and deadly ballet to the work of stunt coordinator Jeff Imada and his team of stunt men and women. There’s none of the fast cut and edits to make an action scene seem more chaotic than it really is. Each brutal fight sequence from the hand-to-hand combat to the shootouts are shot with a wide lens to give the audience a clear view of every move, decision and attack made through the fight. When the camera does move from combatant to combatant it flows from one to another without missing a beat. I will also say that the violence in these fights are quite sudden and brutal. Limbs and heads are cut off with ease that it takes several beats before the audience even realizes what has happened. While the film does have it’s share of action sequences the Hughes Brothers actually seem to hold themselves back from putting in more to keep the fast-pace moving. Instead they use these sudden burst of violence to break whatever monotony may set in during scenes of dialogue.

It is during these downtime from the action that the meat of the story shows itself. The book being protected by Washington’s character may seem to look like a MacGuffin from the onset as he tries to stay on path to deliver it somewhere West. It’s during his brief stop in an unnamed town that we find out just exactly what the book really is. It is also in this part of the film where the audience meets the opposite of Washington’s character in the Carnegie, the town’s dictatorial mayor played by Gary Oldman channeling his inner Stansfield from his time more than a decade ago on the film Leon: The Professional. There really is no one better right now when it comes to playing a villain with some sophistication to go with an equal amount of sociopathic tendencies. Oldman’s Carnegie gets most of the lines in the film and it’s from his lines of dialogue that we learn not just why but also the motivations for his need to have the book in Washington’s possession.

This section of the film where some explaining of the motivations from both leads bring up some interesting ideas about the nature of faith and religion and how both ideas which seem to share a common ground could also be so different from each other. While the ideas of faith and religion gets screen time there’s not much heavy-handed preaching to alienate the audience. Whitta’s script (with some extensive doctoring from a few individuals) gives the audience enough explanation without forcefeeding them. The film leaves it up to the individual viewer to make up their minds about what had been brought up. I do think that the script and the how the two leads in the film were drawn up left little gray area to be explored. We clearly see Washington’s character as the good guy trying to preserve civilization and society as the Good Book teaches while Oldman’s Carnegie wants to use the power of said Book to cement his power and hold over his town and beyond. There definitely could have been room for some more work on the script to actually complicate the two characters’ motivations where both could be seen as correct in what they want done. Instead there’s no delineation as to who is good and who is bad. It is only through Oldman’s performance that the character of Carnegie escapes becoming a one-note villain.

The rest of the cast perform ably enough but still just left to become plot device characters to help move the story forward. It was good to see Jennifer Beals in another major motion picture. The same goes to Ray Stevenson of HBO’s Rome. While their roles were quite small compared to the two leads they still did quite well with what they had to work with. I was surprised to see Tom Waits make an appearance as the town’s Mr. Fixit man and it was a delight to see. Even the small roles played by Michael Gambon and Frances de la Tour didn’t disappoint. Many in the audience, including myself, reacted quite positively to their slightly demented, but funny elder couple. Their time on-screen was brief but they sure made great use of the time they were given.

The one misstep that almost broke the film for me was the miscasting of Mila Kunis in the role of Solara. While I can understand why she looked quite clean in a town and world where everyone’s hygiene was really not a priority she just looked too clean. It seemed like she just stepped out of a Beverly Hills, 90201 remake by way of The Road Warrior. While her performance was good it still paled when compared to the rest of the principals she interacted with. When we finally see what happens to her in the end of the film there’s no reaction of rousing claps, but instead I could hear snickers and more than a few laughs.

While the story was quite good, albeit with some flaws, the film really stands out with its art direction and the work of DP Don Burgess. With the latter, The Book of Eli was given a very washed out looked of browns and greys. There was barely much any color outside of those two that the film, at times, took on a black & white quality in its visual tone. Burgess and the Hughes Brothers’ decision to use the Red HD-camera allowed the team to create a world that’s been turned on its head. This decision also allowed the filmmakers to combine live-action with the matte paintings to show the blasted landscape in the background. But not everything about the look of the film was perfect and/or well-done. At times some of the scenes clearly looked like they were filmed in front of a green-screen. Maybe it was a deliberate choice but one that, at times, became too distracting.

In the end, while not a perfect film, the Hughes Brothers’ The Book of Eli was a very good take on the current spate of post-apocalyptic films. While Hillcoat’s The Road was a depressing and agonizingly morbid take on the same subject, the Hughes Brothers were able to convey the same sentiments with their film but giving enough of a glimmer of hope. The ending doesn’t mean that society is saved by any means, but it does show that the chance for rebuilding is there if given the chance. So, whatever director hell the brothers have been relegated to for most of the last decade this film surely has brought them back from exile. While all was still not forgiven for their work on From Hell they’ve at least gotten back into the good graces of the film-going public and, hopefully, they’ve got more work to come.