Welcome to Late Night Retro Television Reviews, a feature where we review some of our favorite and least favorite shows of the past! On Thursdays, I will be reviewing Highway to Heaven, which aired on NBC from 1984 to 1989. The entire show is currently streaming on Tubi and several other services!

This week, we finish up the pilot for Highway to Heaven, with Jonathan revealing the true nature of his job to Mark and the old people heading to the horse races!

Episode 1.1 “Highway to Heaven: Part Two”

(Dir by Michael Landon, originally aired on September 19th, 1984)

The second half of the pilot for Highway to Heaven opens with things looking up at the retirement community. Everyone is enjoying the new garden. There’s a new sense of community amongst the residents. Even Estelle (Helen Hayes) has finally come out of her room and is now taking care of the dog that Jonathan previously gave her. Sidney Gould (John Bleifer) is especially happy to see Estelle out and about, especially after Estelle agrees to have dinner with him.

The only person who is not happy with the changes that Jonathan has brought to everyone’s lives is Mark Gordon. Mark is still suspicious of Jonathan’s motives and he’s not happy that his sister, Leslie (Mary McCusker), is falling for a man who she really knows nothing about. When Jonathan is having dinner at Leslie’s apartment, Mark breaks into Jonathan’s apartment and discovers that Jonathan owns nothing. There’s not even a toothbrush in the bathroom.

Jonathan catches Mark in his apartment and, after Mark demands to know just who exactly Jonathan is, Jonathan explains that he works for “the Boss.” He travels from location to location, helping people who need help. When Mark demands to know who the Boss is, Jonathan can only look heaven-ward.

Needless to say, Mark is not at all convinced that Jonathan is an angel. But there’s an even bigger problem to deal with! Mr. Sinclair (Joe Dorsey), the owner of retirement home, has sold the land to a developer! Everyone who worked there is now out of a job and everyone who lived there has been given just a few days to move out and find somewhere else to live.

When Jonathan pays Mr. Sinclair a visit, he discovers that Sinclair has spent his life making money in order to get over the shame of being rejected by his high school love. Unfortunately, she’s now dead and Sinclair no longer cares about anyone. Still, Jonathan is able to convince Mr. Sinclair to give him a chance to raise enough money to buy the retirement home.

Mark’s suggestion is that they take the money that they already have and bet it at the tracks. Jonathan is not sure if the Boss would like him gambling but, in the end, he agrees to Mark’s plan. At the tracks, it first appears that the horse that the old people put their money on has lost. But then then Sidney discovers that the person at the betting window accidentally gave him the wrong ticket and — it’s a miracle! They win the money!

The old people are able to buy their retirement home and Mark is now convinced that Jonathan is angel. In fact, Mark is so convinced that he insists on driving Jonathan around the country and helping him out.

(Don’t worry about Leslie. Though she’s upset when Jonathan leaves, a handsome and single man immediately moves in next door to her.)

This episode ends with Jonathan getting into Mark’s car and the two of them driving off, down the highway.

Wow, this was an earnest show. Seriously, there’s not a hint of sarcasm or snarkiness to be found in this episode, which I imagine explains why this show is still airing on the retro stations and streaming on a hundred different sites. To an extent, it’s easy to be dismissive of a show where a bunch of quirky old people got to the race track to win enough money to be able to stay together in their retirement home. There’s nothing subtle not particularly surprising about any of it. I mean, we know there’s no way Helen Hayes and that adorable dog are going to lose their home! But this episode was so achingly sincere in its approach that it worked.

We’ll see if it continues to work next week!

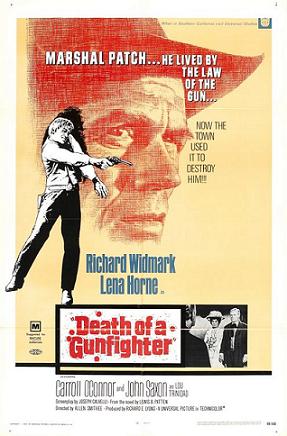

At the turn of the 20th century, the mayor and the business community of Cottonwood Springs, Texas are determined to bring their small town into the modern era. The Mayor (Larry Gates) has even purchased one of those newfangled automobiles that have been taking the country by storm. However, the marshal of Cottonwood Spings, Frank Patch (Richard Widmark), is considered to be an embarrassing relic of the past. Patch has served as marshal for 20 years but now, his old west style of justice is seen as being detrimental to the town’s development. When Patch shoots a drunk in self-defense, the town leaders use it as an excuse to demand Patch’s resignation. When Patch refuses to quit and points out that he knows all of the secrets of what everyone did before they became respectable, the business community responds by bringing in their own gunfighters to kill the old marshal.

At the turn of the 20th century, the mayor and the business community of Cottonwood Springs, Texas are determined to bring their small town into the modern era. The Mayor (Larry Gates) has even purchased one of those newfangled automobiles that have been taking the country by storm. However, the marshal of Cottonwood Spings, Frank Patch (Richard Widmark), is considered to be an embarrassing relic of the past. Patch has served as marshal for 20 years but now, his old west style of justice is seen as being detrimental to the town’s development. When Patch shoots a drunk in self-defense, the town leaders use it as an excuse to demand Patch’s resignation. When Patch refuses to quit and points out that he knows all of the secrets of what everyone did before they became respectable, the business community responds by bringing in their own gunfighters to kill the old marshal. Don’t mess with Charles Bronson.

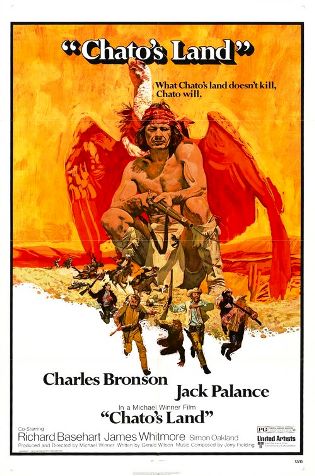

Don’t mess with Charles Bronson.