If you study the history of the International Left in the years immediately following the death of Lenin, it quickly becomes apparent that the era was defined by the rivalry between Joseph Stalin and Leon Trotsky.

Trotsky, the self-styled intellectual who was credited with forming the Red Army and who many felt was Lenin’s favorite, believed that he should succeed Lenin as the leader of Communist Russia. Stalin, the ruthless nationalist who made up in brutality what he lacked in intelligence, disagreed. Stalin outmaneuvered Trotsky, succeeding Lenin as the leader of the USSR and eventually kicking Trotsky out of the country. Trotsky would spend the rests of his life in exile, a hero to some and a pariah to others. While Stalin starved his people and signed non-aggression pacts with Hitler, Trotsky called for worldwide revolution. To Stalin, Trotsky was a nuisance whose continued existence ran the risk of making Stalin look weak. When Trotsky was assassinated in Mexico in 1940, there was little doubt who had given the order. After Totsky’s death, the American Communist Party, which had already been weakened by the signing of the non-aggression pact between Hitler and Stalin, was further divided into Stalinist and Trotskyite factions.

Ideologically, was there a huge difference between Stalin and Trotsky? Many historians have suggested that Trotsky probably would have taken many of the same actions that Stalin took had Trotsky succeeded Lenin. Indeed, the idea that Trotsky was somehow a force of benevolence has more to do with the circumstances of his assassination than anything that Trotsky either said or did. In the end, the main difference between Stalin and Trotsky seemed to be Trotsky was a good deal more charismatic than Stalin. Unlike Trotsky, Stalin couldn’t tell a joke. However, Stalin could order his enemies killed whenever he felt like it and some people definitely found that type of power to be appealing. Trotsky could write essays. Stalin could kill Trotsky.

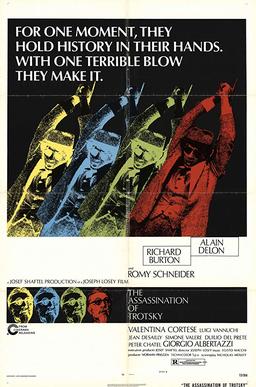

First released in 1972, The Assassination of Trotsky is a cinematic recreation of the events leading to the death of Leon Trotsky in Mexico. French actor Alain Delon plays Frank Jacson, the Spanish communist who was tasked with infiltrating Trotsky’s inner circle and assassinating him with a pickaxe. Welsh actor Richard Burton plays the Russian Trotsky, giving long-winded monologues about world revolution. Italian Valentina Cortese also plays a Russian, in this case Trotsky’s wife, Natalia. And finally, French actress Romy Schneider plays Gita Samuels, who is based on Jacson’s American girlfriend. This international cast was directed by Joseph Losey, an American director who joined the Communist Party in 1946 and who moved to Europe during the McCarthy era.

Losey was an interesting director. Though his first American feature film was the anti-war The Boy With Green Hair, the majority of his American films were on the pulpy side. Not surprisingly, his European films were far more open in their politics. Losey directed his share of undeniable masterpieces, like The Servant, Accident, and The Go-Between. At the same time, he also directed his share of misfires, the majority of which were bad in the way that only a bad film directed by a good director can be. The same director who gave the world The Go-Between was also responsible for Boom!

And then there’s The Assassination of Trotsky. It’s a bit of an odd and rather uneven film. Alain Delon’s performance as the neurotic assassin holds up well and some of his scenes of Romy Schneider have a true erotic charge to them. The scenes of Delon wandering around Mexico with his eyes hidden behind his dark glasses may not add up too much but they do serve as a reminder that Delon was an actor who could make almost any scene feel stylish.

But then we have Richard Burton, looking like Colonel Sanders and not even bothering to disguise his Welsh accent while playing one of the most prominent Russians of the early 20th Century. The film features many lengthy monologues from Trotsky, all of which Burton delivers in a style that is very theatrical but also devoid of any real meaning. As played by Burton, Trotsky comes across as being a pompous phony, a man who loudly calls for world revolution while hiding out in his secure Mexican villa. Now, for all I know, Trotsky could have been a pompous phony. He certainly would not have been the first or last communist to demand the proletariat fight while he remained secure in a gated community. The problem is that the film wants us to admire Trotsky and to feel that the world was robbed of a great man when Jacson drove that pickaxe into his head. That’s not the impression that one gets from watching Burton’s performance. If anything, Burton’s overacting during the assassination scene will likely inspire more laughs than tears.

The Assassination of Trotsky is one of those films that regularly appears on lists of the worst ever made. I feel that’s a bit extreme. The film doesn’t work but Alain Delon was always an intriguing screen presence. (Interestingly enough, Delon himself was very much not a supporter of communism or the Left in general.) The film fails as a tribute to Trotsky but it does make one appreciate Alain Delon.

Previous Icarus Files: