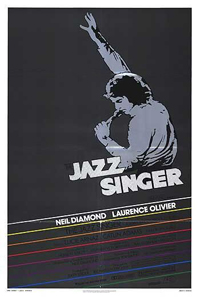

In the 1980 remake of The Jazz Singer, it only takes the film seven minutes to find an excuse to put Neil Diamond in blackface.

Of course, the film was a remake of the 1927 version of The Jazz Singer, which featured several scenes of Al Jolson performing in blackface. In fact, Al Jolson in blackface was such a key part of the film that it was even the image that was used to advertise the film when it was first released. Back in the 20s, Jolson said that wearing blackface was a way of honoring the black artists who created jazz. (As shocking as the image of Al Jolson wearing blackface is to modern sensibilities, Jolson was considered a strong advocate for civil rights and one of the few white singers to regularly appear on stage with black musicians.) Regardless of Jolson’s motives, less-progressively minded performers used blackface as a way to reinforce racial stereotypes and, to modern audiences, blackface is an abhorrent reminder of how black people were marginalized by a racist culture. You would think that, if there was any element of the original film that a remake would change, it would be the lead character performing in blackface.

But nope. Seven minutes into the remake, songwriter Jess Robin (Neil Diamond) puts on a fake afro and dons blackface so that he can perform on stage at a black club with the group that is performing his songs. The group’s name is the Four Brothers and, unfortunately, one of the Brothers was arrested the day of the performance. Jess performs with the group and the crowd loves it until they see his white hands. Ernie Hudson — yes, Ernie Hudson — stands up and yells, “That’s a white boy!” A riot breaks out. The police show up. Jess and the three remaining Brothers are arrested and taken to jail. Jess is eventually bailed out by his father, Cantor Rabinovitch (Laurence Olivier). The Cantor is shocked to discover that his son, Yussel Rabinovitch, has been performing under the name Jess Robin. He’s also stunned to learn that Yussel doesn’t want to be a cantor like his father. Instead, he wants to write and perform modern music. The Cantor tells Yussel that his voice is God’s instrument, not his own. Yussel returns home to his wife, Rivka (Caitlin Adams), and tries to put aside his dreams.

But when a recording artist named Keith Lennox (Paul Nicholas) wants to record one Yussel’s songs, Yussel flies out to Los Angeles. As Jess Robin, he is shocked to discover that Lennox wants to turn a ballad that he wrote into a hard rock number, Jess sings the song to show Lennox how it should sound. The arrogant Lennox is not impressed but his agent, Molly (Lucie Arnaz) is. Soon, Jess has a chance to become a star but what about the family he left behind in New York? “I have no son!” the Cantor wails when he learns about Jess’s new life in California.

I’ve often seen the 1980 version of The Jazz Singer referred to as being one of the worst films of all time. I watched it a few days ago and I wouldn’t go that far. It’s not really terrible as much as its just kind of bland. For someone who has had as long and successful a career as Neil Diamond, he gives a surprisingly charisma-free performance in the lead role. The most memorable thing about Diamond’s performance is that he refuses to maintain eye contact with any of the other performers, which makes Jess seem like kind of a sullen brat. It also doesn’t help that Diamond appears to be in his 40s in this film, playing a role that was clearly written for a much younger artist. Still, when it comes to bad acting, no one can beat a very miscast Laurence Olivier, delivering his lines with an overdone Yiddish accent and dramatically tearing at his clothes to indicate that Yussel is dead to him. Olivier was neither Jewish nor a New Yorker and that becomes very clear the more one watches this film. It takes a truly great actor to give a performance this bad. Diamond, at least, could point to the fact that he was a nonactor given a starring role in a major studio production. Olivier, on the other hand, really had no one to blame but himself.

Still, I have to admit that ending the film with a sparkly Neil Diamond performing America while Laurence Olivier nods in the audience was perhaps the best possible way to bring this film to a close. It’s a moment of beautiful kitsch. The Jazz Singer needed more of that.