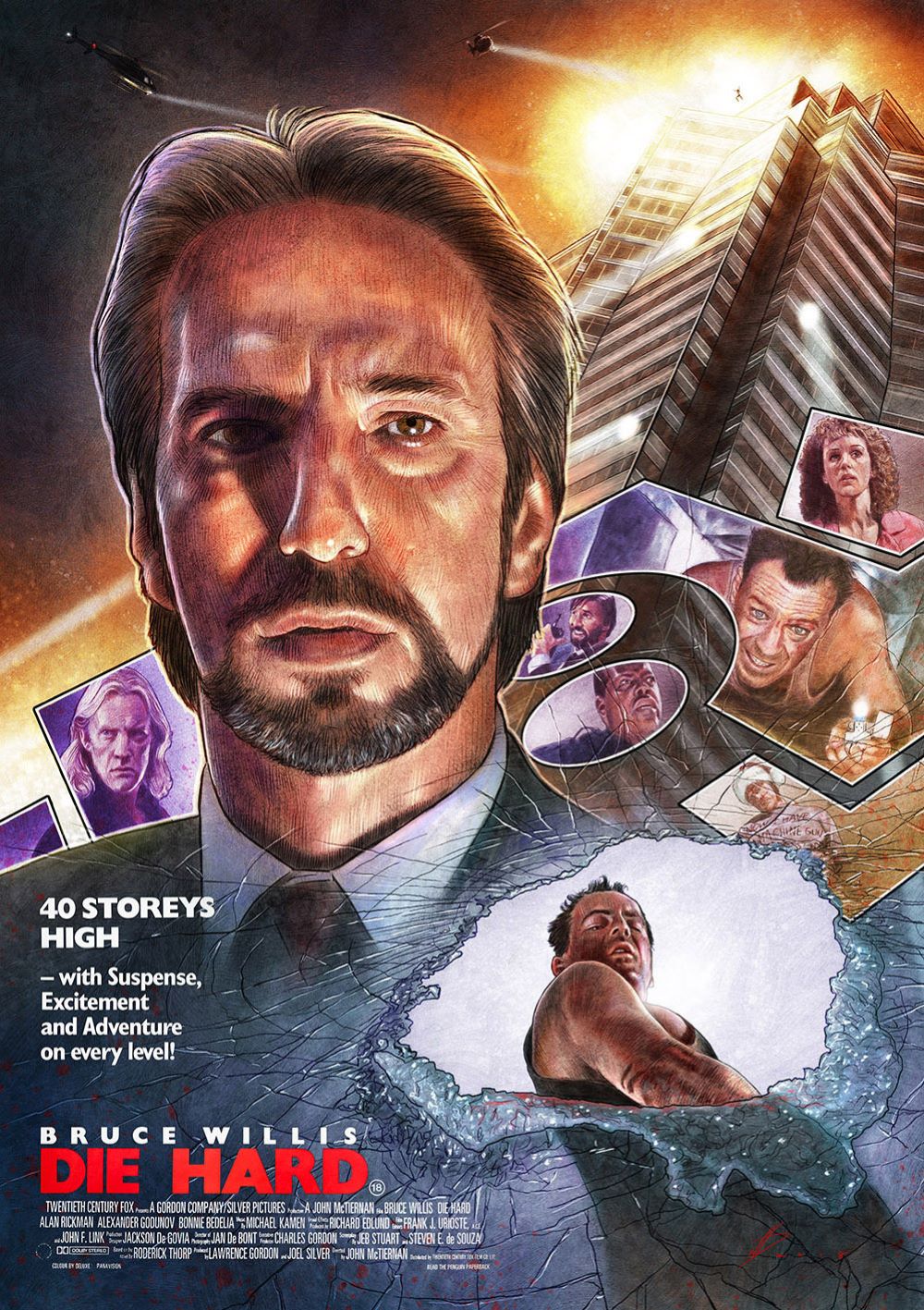

“Welcome to the party, pal!” — John McClane

Die Hard is the ultimate Christmas film (though not the greatest) disguised as an action thriller, blending holiday cheer with high-stakes mayhem in a way that has sparked endless debates and turned it into a seasonal staple for millions. It stands as a landmark action movie and a sharp, character-driven thriller that continues to set the standard for the genre. The film mixes bombast with genuine heart, balancing tension, wit, and raw emotion so effectively that its imperfections only add to its enduring appeal.

Released in 1988 under John McTiernan’s direction, Die Hard follows New York cop John McClane (Bruce Willis) arriving in Los Angeles during the holidays to reconcile with his estranged wife Holly at her office Christmas party in Nakatomi Plaza. He’s fresh off a transcontinental flight, nursing a cocktail of jet lag and marital tension, hoping a festive gathering might thaw the ice between them after her career move to the West Coast has strained their family life. No sooner has he kicked off his shoes—famously leaving him barefoot for most of the chaos—than a disciplined crew of armed robbers, masquerading as terrorists under the command of Hans Gruber (Alan Rickman), storms the building, holding the revelers captive and forcing McClane to fight back shoeless and outgunned amid the towering offices. This lean setup—one man, one skyscraper, one chaotic evening—drives the story’s relentless pace, with straightforward spatial awareness keeping viewers locked into the rising peril. The Christmas setting isn’t just window dressing; twinkling lights, carols on the soundtrack, and a rooftop Santa sleigh add layers of irony and warmth to the gunfire, making the film a peculiar but perfect yuletide watch.

The movie refreshingly casts its action lead as an everyday underdog, full of sarcasm and frailty rather than invincible machismo. McClane takes real damage—he’s slashed by glass, battered by falls, and wheezing from asthma attacks—freaks out under pressure, second-guesses himself constantly, and limps through the ordeal covered in cuts and shards while grumbling about his lousy luck. These moments of raw vulnerability humanize him in a genre often dominated by perfect physiques and unflappable cool. Bruce Willis brings a rumpled, relatable edge to the role, drawing from his TV background on Moonlighting to infuse McClane with quick-witted banter and hangdog charm, making his pigheaded risks and desperate quips—like his tense radio chats or infamous air vent shuffle—land as the outbursts of an ordinary Joe desperate for survival and a way out. Willis’s casting was a gamble at the time, pivoting from wisecracking detective to gritty hero, but it paid off by redefining what an action star could be: flawed, funny, and fiercely determined.

Hans Gruber remains a standout antagonist, living up to every ounce of his legendary status—and remarkably, this was Alan Rickman’s very first film role, launching him into stardom with a performance that still defines screen villainy. Fresh from stage work, Rickman infuses him with suave detachment and subtle menace, his silky British accent dripping with condescension as he portrays a criminal mastermind who approaches the heist like a hostile merger, his cultured facade slipping just enough to reveal cold ruthlessness. Lines like his mocking “Mr. Mystery Guest” taunts or his gleeful disdain for American excess have become iconic, delivered with a theatrical precision that elevates Gruber above typical thugs. Clever writing highlights his contempt for yuppie excess and delight in red tape, while McTiernan’s direction turns their encounters into personal showdowns brimming with verbal sparring beyond mere firepower, turning cat-and-mouse into a battle of intellects as much as endurance.

A strong ensemble bolsters the narrative without bogging down the momentum. Bonnie Bedelia’s Holly exudes quiet strength, proving herself a sharp professional unafraid of bosses or bandits, which elevates her rapport with McClane above clichéd rescue tropes—she’s calling shots from the hostage room and holding her own in tense negotiations. Reginald VelJohnson’s Sergeant Al Powell elevates a stock radio contact into the story’s heartfelt core, offering McClane solace and shared regrets during their poignant nighttime talks about lost family and second chances, creating an unlikely but touching bromance across police lines. Figures like Hart Bochner’s smarmy Ellis, with his coke-fueled deal-making, or William Atherton’s pushy journalist Richard Thornburg, chasing scoops with ruthless ambition, add biting commentary on greed and sensationalism, sharpening the film’s take on ’80s excess and how corporate snakes and media vultures complicate the crisis. Even smaller roles, like the hapless deputy chief or the bickering SWAT team, paint a vivid picture of institutional incompetence that McClane must navigate alone.

Die Hard excels in choreographing escalating clashes within tight quarters, turning the skyscraper into a multi-level chessboard. McTiernan masterfully exploits Nakatomi’s design—raw construction levels with exposed beams, service elevators for ambushes, fire stairs slick with tension, upper decks for sniper duels, and cubicle warrens for close-quarters chaos—to distinguish every skirmish from rote shootouts, ensuring each fight feels unique and earned. Precise editing weaves between McClane’s scrambles, captive dread, robber schemes, and external responders, layering suspense without devolving into explosive filler; the cross-cutting builds dread as plans intersect disastrously. Standout sequences thrill because of careful buildup around deadlines and official blunders, like ill-timed interventions that raise the stakes sky-high. The practical effects—real stunts, squibs, and pyrotechnics—give the action a tangible weight that CGI-heavy modern films often lack, grounding the spectacle in sweat and physics.

Blending laughs with savagery proves the film’s toughest feat, yet it mostly triumphs. McClane’s biting comebacks, taped to dead bodies or barked into walkie-talkies, and the dark comedy amid cop-thug banter sustain levity amid dire threats and mounting casualties, preventing the film from tipping into grim slog. Gags like the executive’s C4 “gift” or Powell’s Twinkie diet poke fun at excess without diffusing danger. Certain gags and era-specific jabs feel dated—like mockery of inept brass or overzealous feds—but this institutional skepticism fuels the plot, portraying red tape and hubris as lethal as automatic weapons, a theme that resonates in any age of bloated bureaucracies.

The film’s action overload, ironically its signature strength, occasionally trips it up. Later stretches bombard with relentless blasts and ballets, prompting some to decry the carnage’s intensity or plot holes from initial reviews, where critics noted the escalating body count’s numbing effect. Elements like tactical decisions by authorities or vault breach logistics falter on nitpicks, relying now and then on lucky breaks to align the chaos, such as perfectly timed discoveries or overlooked details in the heist plan. Fans of taut caper tales might see the wilder antics as indulgence over invention, prioritizing popcorn thrills over airtight logic. Yet these are minor quibbles in a runtime that clocks in under two hours, keeping energy high without exhaustion.

Yet a solid emotional arc lends depth beyond mere spectacle. Fundamentally, it’s about a bullheaded officer confronting his marital neglect, enduring brutal comeuppance while seeking redemption amid the tinsel and terror. His raw confessions to Powell inject humanity that heightens the personal stakes, turning isolated survival into a quest for reconnection. The script, adapted from Roderick Thorp’s novel Nothing Lasts Forever, weaves family drama into the frenzy without halting the pace, making quieter moments—like shared vulnerabilities over radio—punch harder than any explosion.

Technically, Die Hard brims with assured flair bordering on swagger. Cinematographer Jan de Bont’s lenses capture glassy surfaces, mirrors for disorienting reflections, and soaring perspectives to render the tower both glamorous and hostile, a glassy trap turned warzone that mirrors the characters’ fractured relationships. Crisp cuts allow pauses for character amid the rush, preserving brisk tempo without shortchanging development; McTiernan’s post-Predator confidence shines in rhythmic pacing that breathes. Michael Kamen’s soundtrack fuses orchestral surges with jingly carols like “Let It Snow,” amplifying the bizarre fusion of festivity and fusillades that forever fuels “Christmas movie” arguments—ho-ho-hos interrupted by hails of bullets.

Die Hard‘s influence reshaped action cinema, birthing the “Die Hard in a [location]” trope for enclosed thrillers, from buses to battleships, spawning endless imitators chasing its formula. Sequels amplified scale at the cost of grounded heroism, proving surface mimics—snark, stunts, scheming foes—miss the original’s vulnerable punch, as later entries piled on global threats and gadgets. Detractors note it paved paths for bloated pyrotechnics in successors, but that’s on copycats, not this taut gem; its box-office success—over $140 million worldwide—proved audiences craved smart spectacle.

All told, Die Hard delivers razor-sharp, hilarious, masterfully built blockbuster entertainment that ages like fine whiskey. Pairing a rugged everyman lead, suave nemesis, and geography-smart sequences, it raises a benchmark few match. Flaws like overkill blasts or shaky rationale aside, its tension, depth, and gritty laughs cement its throne in action lore, a holiday gift that keeps on giving.