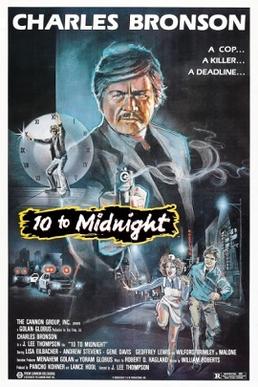

I became obsessed with actor Charles Bronson in 1986 after receiving a VHS copy of DEATH WISH 3 as a Christmas present. Going along with that obsession was my desire to see every Charles Bronson movie that had ever been made. As much as I enjoyed re-watching DEATH WISH 3, it was always a treat when I could rent a different Bronson film at the video store. The current Bronson movie at the video store in 1987 that appealed to me as a 13 year old boy was MURPHY’S LAW, so I wanted to rent it as often as possible. There were even a couple of times when different friends asked me to spend the night, and I had one requirement for saying yes… that we rent MURPHY’S LAW! Y’all, don’t think too bad of me for this admission. Remember, I was only 13 years old, I couldn’t drive, and I didn’t have a job so if I had to use a friend’s mom to get my Bronson fix, that’s just what I had to do! Based on the timing of my initial Bronson obsession, DEATH WISH 3 and MURPHY’S LAW are 1-2 in the films that I’ve watched the most times during my life.

In MURPHY’S LAW, Charles Bronson plays Jack Murphy, a tough cop who seems to be experiencing a series of unfortunate events:

- A thief named Arabella McGee (Kathleen Wilhoite) tries to steal Murphy’s car and drives it through the window of a pizzaria. We know that’s his car because he loudly proclaims, “That’s MY car!!” He even wastes money on a sack of groceries by throwing it at his car while she’s driving away. He’s able to chase her down on foot, but she kicks him in the testicles and runs off leaving him doubled over in pain, grocery-less, and clutching the family jewels!

- A mafia kingpin named Frank Vincenzo (Richard Romanus) wants to kill him because Murphy was forced to shoot and kill the kingpin’s brother. We know the cop and the kingpin don’t like each other, because a little before the shooting they have a slight disagreement in front of the mafioso’s mother over whether the brother is a scum-sucking pimp or a talent agent. Unable to resolve the debate amicably, the mafioso inquires as to whether or not Jack has ever heard of “Murphy’s Law, if anything can possibly go wrong it will?” Murphy responds with an alternative version of Murphy’s Law, the only law that he knows, and one that I greatly prefer. You get the feeling that this argument may be revisited later in the film.

- Murphy’s now ex-wife Jan (Angel Tompkins) is performing extremely artistic striptease routines at a local club called Madam Tong’s. She’s also making love to the manager of the club. Rather than drinking at home alone until he passes out like most depressed men, Murphy hangs out at Madam Tong’s watching her shake her goodies for a bunch of horny lowlifes, before following them home and watching from outside until they turn off the bedroom lights. Very sad indeed.

- And here’s the worst part, on one of those typical nights where he’s obsessively stalking his wife, another mystery woman (Carrie Snodgress) knocks him in the head, shoots the slimy manager and Mrs. Murphy with his gun, and then frames him for their murders. Arrested for the murders and subsequently handcuffed to the thief who tried to steal his car, Murphy must stage a daring helicopter jailbreak in order to find out who framed him and clear his name before everything and everyone he holds dear is taken from him!

There are several reasons that I loved MURPHY’S LAW back in the eighties, and that I still enjoy it now. First, of course, is Charles Bronson. He was around 64 years old when he filmed MURPHY’S LAW, but he’s still in great physical condition in 1986. One of Bronson’s greatest strengths is his screen presence, and he still dominates each frame he’s in. Second, the film has an excellent supporting cast. Carrie Snodgress is having a ball playing the main villain in the film. I’ve seen her in quite a few movies, like PALE RIDER with Clint Eastwood, and 8 SECONDS with Luke Perry, but I’ve never seen her in a role like this. Snodgress was nominated for an Oscar for her role in a 1970 film called DIARY OF A MAD HOUSEWIFE. I’ve never seen that one before, but I should probably check it out! I love Kathleen Wilhoite as Arabella McGee, the thief who ends up handcuffed to Bronson. Her vocabulary, while probably not very realistic for the streets of LA at the time, was hilarious to me as a teenager. I enjoy calling the people I love “snot licking donkey farts” on occasion to this very day. It’s Kathleen Wilhoite singing the title song over the closing credits! And Robert F. Lyons is very special to me in his role as Art Penney, Jack Murphy’s partner. We got to interview him on the THIS WEEK IN CHARLES BRONSON podcast about his roles on DEATH WISH 2, 10 TO MIDNIGHT, and MURPHY’S LAW. He was so generous with his time, and just a hell of a nice guy! I’ve attached a link to the YouTube video of the interview with Mr. Lyons if you’re interested in the great stories he tells us about his time in Hollywood! Finally, MURPHY’S LAW was directed by J. Lee Thompson, my personal favorite director who worked with Bronson. Thompson directed Bronson in 9 different films, beginning with ST. IVES in 1976 and ending with KINJITE: FORBIDDEN SUBJECTS in 1989. No matter the material, you always knew that Thompson would deliver a film with a certain quality that made Bronson look good!

I’ll always be a fan of MURPHY’S LAW, partly for nostalgic reasons, but mainly because I think it’s an entertaining mid-80’s action film for Bronson at a time when he was one of the kings of the video store!

To quote John McClane, “How can the same shit happen to the same guy twice?”

To quote John McClane, “How can the same shit happen to the same guy twice?”

Having just graduated from West Point, Lt. Jeff Knight (Michael Dudikoff, the American Ninja himself) is sent to Vietnam and takes over a battle-weary platoon. Lt. Knight has got his work cut out for him. The VC is all around, drug use is rampant, and the cynical members of the platoon have no respect for him. When Lt. Knight is injured during one of his first patrols, everyone is so convinced that he’ll go back to the U.S. that they loot his quarters. However, Knight does return, determined to earn the respect of his men and become a true platoon leader!

Having just graduated from West Point, Lt. Jeff Knight (Michael Dudikoff, the American Ninja himself) is sent to Vietnam and takes over a battle-weary platoon. Lt. Knight has got his work cut out for him. The VC is all around, drug use is rampant, and the cynical members of the platoon have no respect for him. When Lt. Knight is injured during one of his first patrols, everyone is so convinced that he’ll go back to the U.S. that they loot his quarters. However, Knight does return, determined to earn the respect of his men and become a true platoon leader! What is Murphy’s Law?

What is Murphy’s Law?