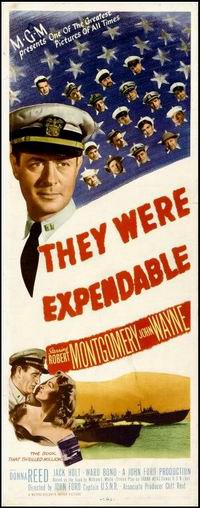

In December of 1941, Lt. John Brickley (Robert Montgomery) commands a squadron of Navy PT boats, based in the Philippines. Brickley is convinced that the small and agile PT Boats could be used in combat but his superior officers disagree, even after viewing a demonstration of what they can do. Brickley’s second-in-command, Rusty (John Wayne), is frustrated and feels that he will never see combat. That changes when the Japanese attack Pearl Harbor and then turn their attention to the Philippines. Brickley gets his chance to show what the PT boats can do but both he and his men must also deal with the terrible risks that come with combat. Brickley and his men have been set up to fight a losing battle, only hoping to slow down the inevitable Japanese onslaught, because both they and their boats are considered to be expendable. The hot-headed Rusty learns humility when he’s sidelined by blood poisoning and he also falls in love with a nurse, Sandy (Donna Reed). However, the war doesn’t care about love or any other plans that its participants may have. With the invasion of the Philippines inevitable, it just becomes a question of who will be sent with MacArthur to Australia and who will remain behind.

In December of 1941, Lt. John Brickley (Robert Montgomery) commands a squadron of Navy PT boats, based in the Philippines. Brickley is convinced that the small and agile PT Boats could be used in combat but his superior officers disagree, even after viewing a demonstration of what they can do. Brickley’s second-in-command, Rusty (John Wayne), is frustrated and feels that he will never see combat. That changes when the Japanese attack Pearl Harbor and then turn their attention to the Philippines. Brickley gets his chance to show what the PT boats can do but both he and his men must also deal with the terrible risks that come with combat. Brickley and his men have been set up to fight a losing battle, only hoping to slow down the inevitable Japanese onslaught, because both they and their boats are considered to be expendable. The hot-headed Rusty learns humility when he’s sidelined by blood poisoning and he also falls in love with a nurse, Sandy (Donna Reed). However, the war doesn’t care about love or any other plans that its participants may have. With the invasion of the Philippines inevitable, it just becomes a question of who will be sent with MacArthur to Australia and who will remain behind.

One of John Ford’s best films, They Were Expendable is a tribute to the U.S. Navy and also a realistic look at the realities of combat. The movie features Ford’s trademark sentimentality and moments of humors but it also doesn’t deny that most of the characters who are left behind at the end of the movie will not survive the Japanese invasion. Even “Dad’ Knowland (Russell Simpson), the fatherly owner of a local shipyard who does repair work on the PT boats, knows that he’s expendable. He resolves to meet his fate with a rifle in hand and a jug of whiskey at his feet. Rusty, who starts out thirty for combat, comes to learn the truth about war. Ford was one of the many Hollywood directors who was recruited to film documentaries during World War II and he brings a documentarian’s touch to the scenes of combat.

Robert Montgomery had previously volunteered in France and the United Kingdom, fighting the Axis Powers before America officially entered the war. After the war began, he entered the Navy and he was a lieutenant commander when he appeared in They Were Expendable. Montgomery brought a hardened authenticity to the role of Brickley. (Montgomery also reportedly directed a few scenes when Ford was sidelined with a broken leg.) John Wayne is equally good in the role of the hot-headed Rusty, who learns the truth about combat and what it means to be expendable. The cast is full of familiar faces, many of whom were members of the John Ford stock company. Keep an eye out for Ward Bond, Cameron Mitchell, Leon Ames, Jack Holt, and Donald Curtis.

They Were Expendable is one of the best of the World War II movies. It’s a worthy film for Memorial Day and any other day.