In the projects of Chicago, Byron Harper (Michael Warren) runs a nonprofit basketball farming system and helps black kids, many of whom would have no other prospects other than a live of poverty or crime, to find a home in college basketball programs. Byron is passionate about what he does but he’s also a stern taskmaster and not quick to forgive. When one of his best players, Casey (Nigel Miguel), developed a drinking problem, Byron kicked him off his team. Byron’s main concern is his stepson, Truth (Victor Love). Truth is a great basketball player but also has an addiction to cocaine and an attitude problem.

In the projects of Chicago, Byron Harper (Michael Warren) runs a nonprofit basketball farming system and helps black kids, many of whom would have no other prospects other than a live of poverty or crime, to find a home in college basketball programs. Byron is passionate about what he does but he’s also a stern taskmaster and not quick to forgive. When one of his best players, Casey (Nigel Miguel), developed a drinking problem, Byron kicked him off his team. Byron’s main concern is his stepson, Truth (Victor Love). Truth is a great basketball player but also has an addiction to cocaine and an attitude problem.

For reasons that are never made clear, white lawyer Zack Telander (D.B. Sweeney) shows up on the court and says he wants to play one-on-one with Byron. Everyone assumes that Zack is a drug dealer and they tell him to get lost. But when one of the players is shot, Zack is the only person at the court who has a car. Zack rushes the player to the hospital and he wins Byron’s trust. Byron needs Zack to look over a professional contract that is being offered to Truth by sleazy sports agent David Racine (Richard Jordan).

For reasons that are again never made clear, Byron tells Zack to coach some of the more troubled players on the court, including Casey. At first, Zack isn’t much of a coach but eventually, he gets the players to trust him and start playing like a team. He also tries to get burned-out Matthew Lockhart (Bo Kimble) to start playing the game again.

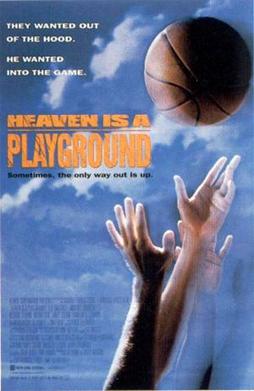

Heaven Is A Playground is a mess of a movie that doesn’t really seem to be sure what it wants to say about basketball, the projects, or race relations. The main problem is that a lot of the decisions made by Byron and Zack don’t make any sort of logical sense. Moments of broad comedy are mixed with moments of high drama and it makes for an unconvincing and overly melodramatic sports movie.

Heaven Is A Playground had a long pre-production phase. At one point, a young Michael Jordan agreed to play the role of Matthew Lockhart. By the time the film actually went into production, Jordan was a superstar and had neither the time (nor, probably, the desire) to co-star in a low-budget sports movie. After the movie flopped, director Randall Fried sued Jordan for breach-of-contract, claiming that he caused the film’s box office failure by refusing to appear in it and, as a result, Fried’s directorial career stalled. In the suit, Fried claimed that he was on the verge of being “the next Steven Spielberg” until Jordan refused to do his film. The jury found Jordan not liable and awarded him $50,000.

(Trying to sue Michael Jordan was a terrible idea in 1998 and it’s probably still a terrible idea today. People love Jordan!)

Personally, I have to say that Mike made the right decision.