“Creature stole my Twinkie.” – Eugene

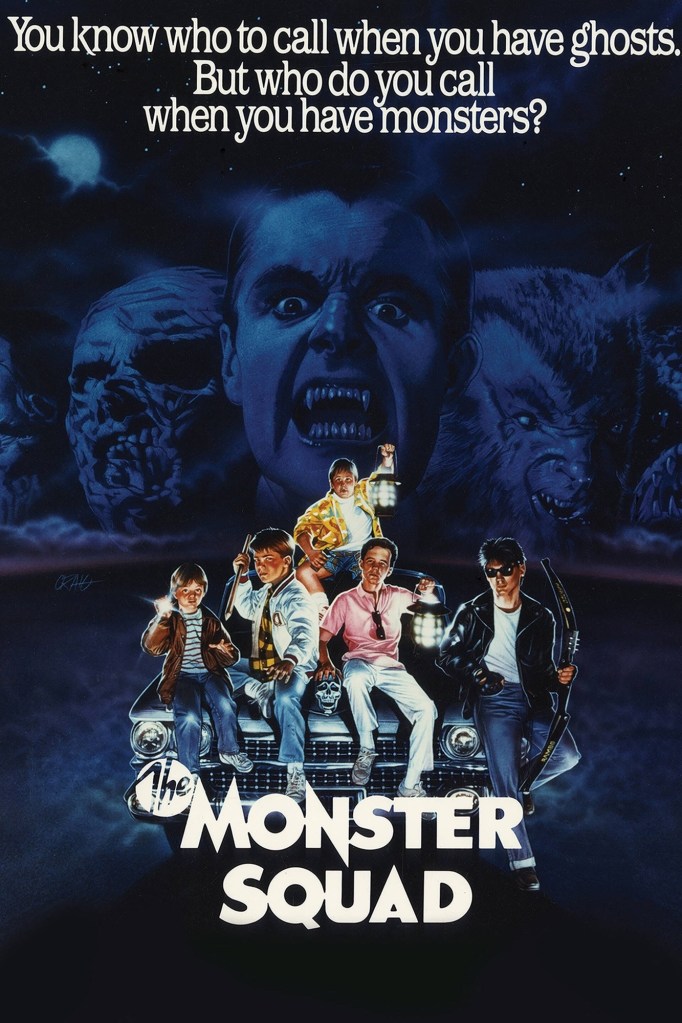

Released in 1987, The Monster Squad has lived one of those strange afterlives that cult films sometimes enjoy—ignored or even ridiculed upon release, only to become a beloved artifact for the generation that found it later on VHS. Directed by Fred Dekker and co-written with Shane Black, the movie occupies an awkward but endearing space between horror, comedy, and kids’ adventure. It never fully settles into one tone, and that’s part of both its charm and its problem. Watching it today, the film feels like The Goonies took a detour through a drive-in double feature of Dracula and The Wolf Man. It’s clunky, funny, occasionally mean-spirited, and loaded with enthusiasm—qualities that make it a thoroughly guilty pleasure for fans of ’80s genre mashups.

The story wastes no time getting into its madcap premise. A group of suburban preteens calling themselves “The Monster Squad” find that the classic Universal-style monsters are real, and worse, they’ve come to town. Count Dracula has a plan to plunge the world into darkness using an ancient amulet, and to succeed he enlists a roster of familiar faces: Frankenstein’s Monster, the Mummy, the Gill-Man, and the Wolf Man. This roster is fan-service before fan-service was a marketing term—a kid’s monster toybox brought to life. The squad, of course, must stop them, armed with comic-book knowledge, wooden stakes, and a blend of reckless courage and youthful sarcasm.

Dekker’s direction and tone play like a movie made for kids but smuggled in some heavy teenage energy. There’s violence, crude jokes, and occasional language that Hollywood would never let slip into a PG-friendly franchise today. Yet that rough edge is part of why The Monster Squad aged into cult status. It’s unapologetically of its time, operating on the belief that kids can handle scares as long as they’re fun and that suburban fantasy can, for a while at least, coexist with real danger. The movie’s depiction of childhood feels filtered through a stack of comic books and Creepshow issues—hyper absurd but still emotionally grounded in a way only ’80s adventure films seemed to pull off.

The kids themselves are a mixed bunch of believable archetypes. There’s Sean (André Gower), the de facto leader with a bedroom plastered in monster movie posters; Patrick (Robby Kiger), his wisecracking sidekick; Rudy (Ryan Lambert), the too-cool-for-school older kid who smokes, rides a bike, and somehow becomes the squad’s weapons specialist; and Eugene (Michael Faustino), the youngest, who still sleeps with his dog and writes letters to the Army for backup. They’re joined by Horace, nicknamed “Fat Kid,” played with surprising vulnerability by Brent Chalem. Each character is drawn broadly but memorably, and even when the dialogue veers into dated humor, there’s an underlying sincerity. You can tell Dekker and Black really liked these kids. They might use slingshots and one-liners, but what unites them is their intense sense of loyalty to one another—the kind of friendship that survives both bullies and broomstick-wielding vampires.

If there’s an emotional anchor, oddly enough, it’s the relationship between the squad and Frankenstein’s Monster, played by Tom Noonan in an unexpectedly gentle performance. When the creature befriends the kids, particularly little Phoebe (Ashley Bank), the film shifts momentarily from wisecracks to something close to tenderness. Noonan gives the character a shy uncertainty, a weary loneliness that offsets the visual absurdity of the rubbery monsters around him. There’s even a tinge of tragedy in his final act, which echoes Frankenstein’s literary roots—a moment of real feeling buried inside an otherwise loud and gleefully messy creature romp.

The monsters themselves, created by legendary effects artist Stan Winston, are among the film’s biggest draws. Each design feels like a loving upgrade to the old Universal look—recognizable but more feral, angular, and rooted in late-’80s aesthetics. The Wolf Man, for example, looks simultaneously comic and menacing, while the Gill-Man costume still impresses for its texture and movement decades later. The decision not to rely on stop motion or heavy opticals gives the monsters a tactile presence that CGI could never capture. There’s something about watching full-bodied suits and prosthetics move in real space that makes the threats feel tangible even when the stakes are goofy. These creatures are fun to look at, even when the script doesn’t give them much to do beyond roar and stalk across smoke-filled sets.

Shane Black’s fingerprints are all over the dialogue—the sardonic banter, the genre in-jokes, the affection for both pulp tropes and subverting them. But perhaps because the film was marketed partly as family adventure and partly as horror spoof, it often can’t decide whether to play sincere or ironic. Some scenes lean heavily on nostalgic affection for monster movies, while others feel almost mean in their mockery of small-town innocence. The tone whiplash means The Monster Squad doesn’t build much consistent momentum; one minute it’s heartfelt, the next it’s a barrage of sarcastic one-liners. Still, its rough tonal juggling has a ragtag energy that keeps it lively, and the sheer commitment to blending genres is endearing.

When it comes to pacing, the movie flies by in under 80 minutes, which turns out to be both blessing and curse. On one hand, there’s no filler—every scene moves briskly to the next piece of monster mayhem. On the other, the movie’s emotional beats and mythology barely have time to breathe. We get glimmers of backstory (like Dracula’s cryptic hunt for the amulet and Van Helsing’s prologue battle) that hint at a larger world that the film never really explores. You sense that Dekker and Black were operating under the fantasy logic of childlike storytelling: don’t explain too much, just move fast enough that no one questions it. It works, more or less, because of the film’s sheer enthusiasm, but it leaves you imagining a richer version of this story that never quite made it onscreen.

Looking back from today’s lens, some parts of The Monster Squad show their age more harshly. Certain lines and stereotypes that went unnoticed in the ’80s now feel jarring, even uncomfortable, and the film’s cavalier tone sometimes undercuts moments that should feel more innocent. Yet despite that, most viewers who revisit it with awareness of its era find themselves disarmed by its sense of fun. There’s no cynicism driving it—it’s pure genre love, messy and sincere, like a handmade Halloween costume that’s somehow cooler precisely because it’s imperfect. The film represents a time when kids’ movies were allowed to have teeth, blood, and a few scary moments, trusting that a young audience could handle being spooked without needing everything smoothed over.

For many fans, The Monster Squad works less as a polished film and more as an experience—a flashback to VHS sleepovers, bad pizza, and rewinding favorite scenes. The movie’s newfound appreciation, fueled by screenings and documentaries like Wolfman’s Got Nards, speaks to that nostalgic bond. It’s less about objective greatness and more about the feeling it preserves. Sure, some of the jokes fall flat, and the plot functions mostly as connective tissue between monster gags, but few movies embody the gleeful chaos of late-’80s pop horror as affectionately as this one does.

The Monster Squad earns its title. It’s not a flawless film, nor even a particularly coherent one, but it’s deeply fun, carried by the conviction that monsters—real or imaginary—are made to be fought with courage, humor, and friends who have your back. Watching it now is like flipping through an old comic book you used to love: you can see every crease and faded color, but that doesn’t make it any less special. And in a cinematic era saturated with irony and nostalgia pastiche, The Monster Squad still feels refreshingly earnest about its own weirdness. Maybe that’s its secret power.