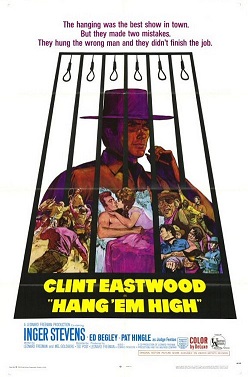

1889. The Oklahoma Territory. A former lawman-turned-cattleman named Jed Cooper (Clint Eastwood) is falsely accused of working with a cattle thief. A group of men, led by Captain Wilson (Ed Begley) lynch him and leave Cooper hanging at the end of a rope. Marshal Dave Bliss (Ben Johnson) saves Cooper, cutting him down and then taking him to the courthouse of Judge Adam Fenton (Pat Hingle). Fenton, a notorious hanging judge, is the law in the Oklahoma territory. Fenton makes Cooper a marshal, on the condition that he not seek violent revenge on those who lynched him but that he instead bring them to trial. Cooper agrees.

1889. The Oklahoma Territory. A former lawman-turned-cattleman named Jed Cooper (Clint Eastwood) is falsely accused of working with a cattle thief. A group of men, led by Captain Wilson (Ed Begley) lynch him and leave Cooper hanging at the end of a rope. Marshal Dave Bliss (Ben Johnson) saves Cooper, cutting him down and then taking him to the courthouse of Judge Adam Fenton (Pat Hingle). Fenton, a notorious hanging judge, is the law in the Oklahoma territory. Fenton makes Cooper a marshal, on the condition that he not seek violent revenge on those who lynched him but that he instead bring them to trial. Cooper agrees.

An American attempt to capture the style of the Italian spaghetti westerns that made Eastwood an international star, Hang ‘Em High gives Eastwood a chance to play a character who is not quite as cynical and certainly not as indestructible as The Man With No Name. Cooper starts the film nearly getting lynched and later, he’s shot and is slowly nursed back to health by a widow (Inger Stevens). Cooper is not a mythical figure like The Man With No Name. He’s an ordinary man who gets a lesson in frontier justice as he discovers that, until Oklahoma becomes a state, Judge Fenton feels that he has no choice but to hang nearly every man convicted of a crime. (Judge Fenton was based on the real-life hanging judge, Isaac Parker.) Over the course of this episodic film, Cooper becomes disgusted with frontier justice.

Hang ‘Em High is a little on the long side but it’s still a good revisionist western, featuring a fine leading performance from Clint Eastwood and an excellent supporting turn from Pat Hingle. The film’s episodic structure allows for Eastwood to interact with a motley crew of memorable character actors, including Bruce Dern, Dennis Hopper, L.Q. Jones, Alan Hale (yes, the Skipper), and Bob Steele. Hang ‘Em High has a rough-hewn authenticity to it, with every scene in Fenton’s courtroom featuring the sound of the gallows in the background, a reminder that justice in the west was often not tempered with mercy.

Historically, Hang ‘Em High is important as both the first film to be produced by Eastwood’s production company, Malpaso, and also the first to feature Eastwood acting opposite his soon-to-be frequent co-star, Pat Hingle. Ted Post would go on to direct Magnum Force.