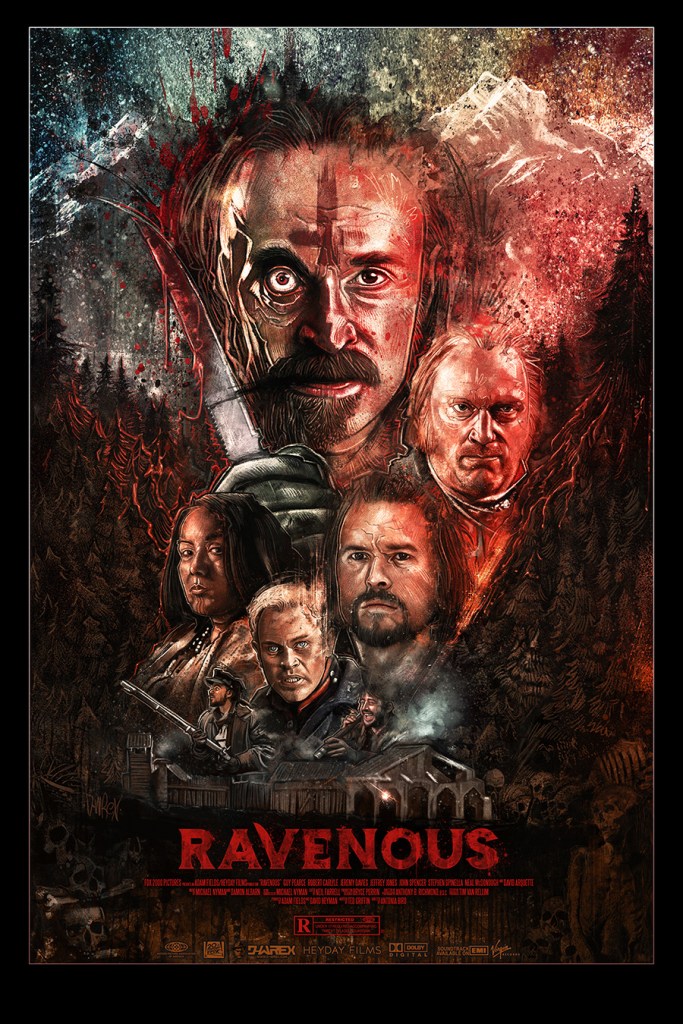

“Morality… is the last bastion of a coward.” — Colonel Ives

Ravenous remains one of the most fascinating and thematically daring horror films of the late 1990s—a layered meditation on hunger, morality, and the consuming appetite of empire disguised as a tale of survival. Set against the punishing winter backdrop of the Mexican-American War, the film centers on Lieutenant John Boyd, a soldier burdened by cowardice and guilt, sent to an isolated military outpost in the Sierra Nevadas. When a frostbitten stranger stumbles into camp with a horrifying tale of survival, the line between the living and the devoured—and between humanity and monstrosity—begins to blur.

At first glance, Ravenous is a dark horror film about cannibalism in a remote frontier fort. What distinguishes it is the way it transforms that premise into a meditation on civilization and consumption. The screenplay, written by Ted Griffin, draws inspiration from historical accounts such as the Donner Party and Alfred Packer—stories of pioneers who resorted to cannibalism to survive brutal winters. Griffin threads these historical horrors into a broader allegory about 19th-century American expansionism: a national hunger for land, power, and progress that consumes everything in its path, including its own humanity.

The mythological backbone of Ravenous lies in the inclusion of the wendigo, a spirit from Native American folklore. In Algonquin and Ojibwe tradition, the wendigo is born of greed and gluttony, a monstrous being that grows stronger and more grotesque with each act of consumption. The tale served as a warning against selfishness, warning that those who devour others—figuratively or literally—lose their humanity in return. Bird and Griffin seamlessly integrate this legend into the film’s themes, using the wendigo to mirror the psychological and cultural costs of empire. The story implies that the wendigo is not confined to mythic forests but lives in the blood of every nation that feeds on others to survive.

The fort where the story unfolds functions as both a stage and symbol: an outpost of civilization planted in the wilderness, claiming righteousness while sustained by exploitation. As starvation and moral decay take hold, the soldiers’ pretense of order crumbles. The isolated setting reflects the broader American project—civilization advancing through conquest yet losing its moral center in the process. The Native nations displaced and destroyed during expansion, reduced to resources or obstacles, become the unseen victims of this devouring drive. The film reframes cannibalism as a metaphor for Manifest Destiny itself—the act of consuming people, land, and spirit under the guise of progress.

That central metaphor gains power through the film’s performances. Guy Pearce delivers a subdued yet deeply expressive performance as Boyd, embodying the moral paralysis of a man trapped between guilt and survival. His silences, glances, and hesitations speak louder than any dialogue, conveying an internal conflict between virtue and instinct. Through him, the film explores how the will to endure can erode the boundaries of conscience.

Robert Carlyle, as Colonel Ives, stands in vivid contrast—charismatic, witty, and terrifyingly self-assured. He plays the role with the infectious energy of a man liberated by his own monstrosity, wearing sin as philosophy. For Ives, cannibalism is not horror but a revelation—a means to transcend weakness and embrace dominance. His eloquent justifications turn atrocity into ideology, echoing the rationalizations of expansionist politics. It is no coincidence that his confidence parallels Boyd’s doubt; the two men form mirror halves of a single corrupted ideal.

Director Antonia Bird’s touch elevates Ravenous from a historical thriller to a surreal moral fable. She handles violence and absurdity with equal precision, oscillating between grim horror and deadpan humor in a way that keeps viewers uneasy yet enthralled. Her direction never treats the horror as spectacle alone—every moment of gore carries weight, testing the limits of empathy and survival. Moments of unexpected humor punctuate the brutality, serving as a reminder that even atrocity can become ordinary when normalized by power.

While the fusion of dark comedy and horror lends the film its originality, it may also unsettle some viewers. The tonal shifts—helped by Michael Nyman and Damon Albarn’s strange, minimalist score—create an atmosphere that feels intentionally dissonant. This mix may challenge those expecting a traditional horror film, but it reinforces Bird’s vision of moral chaos. The unease generated by those shifts mirrors the absurdity of history itself: how horrors can coexist with banality, how laughter can accompany destruction.

The wendigo myth binds all these elements together. Bird portrays it less as a creature and more as a condition—one that spreads through ideology, greed, and the illusion of progress. The spirit of the wendigo thrives wherever ambition turns men into predators and justifies their violence as destiny. In this sense, every character becomes a reflection of national hunger, caught in a metaphorical cycle of consumption. The act of eating flesh becomes a stand-in for the broader devouring inherent in colonization: of land, of native culture, of moral identity.

By framing the frontier as an arena of both physical and spiritual starvation, Ravenous reimagines American history as a feast of self-destruction. It suggests that survival is often indistinguishable from conquest—both are rooted in the urge to consume. Even at its most surreal or ironic moments, the film refuses to let its viewers forget that the hunger at its center is not merely for sustenance but for dominion.

Though underappreciated upon release, Ravenous has since earned recognition as a rare film that wields gore and satire to expose deeper truths. Bird’s control of tone, Griffin’s allegorical writing, and the actors’ opposing energies fuse into something that transcends genre. The result is a story that both horrifies and compels, holding a cracked mirror to the myth of progress.

The wilderness of Ravenous is vast, beautiful, and pitiless—a perfect reflection of the American spirit it depicts. It is a land that promises renewal but demands devouring, a landscape haunted by the ghosts of all it has consumed. The film endures not simply as a parable of survival, but as a meditation on empire, appetite, and the fragile line separating civilization from savagery.

Both grotesque and profound, Ravenous gnaws not only at flesh but at the conscience, forcing us to confront what happens when hunger—whether for life, for power, or for victory—becomes the only morality left.