Is Rob Zombie a good filmmaker?

That’s the question that every horror fan has to ask themselves at some point. Needless to say, Zombie has a huge following and no one can doubt his love for the genre. And yet, despite that, it seems that Zombie’s detractors will always be as outspoken as his fans. His fans point out that Zombie makes movies that literally feel as if they’re filmed nightmares and that, as a committed horror fan, he’s willing to go further in his quest to shock you than most mainstream filmmakers. His detractors, meanwhile, tend to see Zombie as an excessive filmmaker who often uses an abundance of style to cover for a weak narrative.

Personally, I’m somewhere in the middle when it comes to Zombie. I think, as a storyteller, Rob Zombie does occasionally struggle to maintain a coherent narrative but, at the same time, I think his strengths as a director ultimately overcome his weaknesses. As a visual filmmaker, he’s a lot stronger than he’s often given credit for and I don’t think anyone would criticize the way that he uses music in his films. He may not be the strongest director of actors but he’s got a good eye for casting and he’s given work to some of our best character actors (Sid Haig, Malcolm McDowell, Brad Dourif, William Forsythe, and the late Karen Black, just to name a few). If his films are extremely graphic and bloody … well, that’s the current state of horror. If anything, I would argue that Zombie deserves credit for unapologetically embracing the mantle of being a 21st century grindhouse filmmaker.

That said, Rob Zombie’s films rarely seem to be as good on a second viewing as they were during the first. He’s one of those directors who comes at you strong that, to a certain extent, his films almost beat you into submission. During the first viewing of one of Zombie’s films, it’s not unusual to be overwhelmed by all the style and the music and the gore and the over-the-top characterizations. Even if you don’t like the film itself, it definitely makes an impression on you. It’s only on repeat viewing that you might start to notice that Zombie’s narratives are often rather clumsily slapped together. Several times, Zombie’s visual style seems to dictate the story as opposed to the other way around.

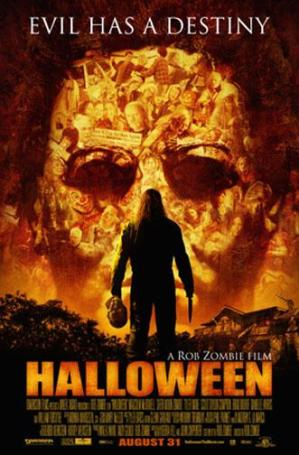

That was certainly the case with his 2007 remake of Halloween. While the film follows the same basic plot as John Carpenter’s original, it also spent a lot more time delving into the past of Michael Myers (Daeg Faerch as a child, Tyler Mane as an adult). It was obvious that Zombie was far more interested in Michael than in any of his victims. (Carpenter took the exact opposite approach, developing the characters of Annie, Laurie, and Linda and allowing Michael to remain a cipher.) As a result, the first half of the film deals with Michael and his dysfunctional childhood while only the second half features Michael escaping and returning to Haddonfield. Laurie, Annie, and Lynda are well-played by Scout Taylor-Compton, Danielle Harris, and Kristina Klebe but ultimately, they all remain rather generic.

The first time I saw Rob Zombie’s Halloween, I thought it was one of the most disturbing films that I had ever seen. I should clarify that I mean that in a good way. Zombie’s Michael was truly terrifying but, at the same time, Zombie portrayed him as a kid who never had a chance. Whereas Carpenter’s Michael started the film as a fresh-faced little boy dressed up like a clown and holding a bloody knife, Zombie’s Michael is born into a world of chaos and darkness. With his dysfunctional childhood, it was hard not to feel that Michael never had a chance. Feeling abandoned by both his family and, eventually, his therapist, Michael retreated into a world of pure anger and hate. Whereas John Carpenter’s Michael rarely seemed to be angry (instead he was just relentless), Zombie’s Michael is rage personified.

Unfortunately, Zombie’s Halloween spends so much time on Michael and his mother (Sheri Moon Zombie) and Dr. Loomis (Malcolm McDowell, perfectly cast) that it doesn’t leave much time for the night he came home. Essentially, the entirety of Carpenter’s original film is crammed into the film’s second half and, on repeat viewings, you can’t ignore how incredibly rushed it all feels. It’s obvious that Zombie’s heart was in the first half of the film. In the second half, he’s just going through the slasher movie motions.

Rob Zombie’s Halloween is definitely a flawed film. John Carpenter’s original remains the superior Halloween but, to be honest, I don’t think Rob Zombie would deny that. Zombie set out not to replace Carpenter’s Halloween but to tell a different version of the same story. When Zombie’s Halloween works, it really works. Flawed as it may be, Halloween proves that Rob Zombie is a talented filmmaker, albeit one with room to grow.

As for Halloween II … well, we’ll talk about that later…