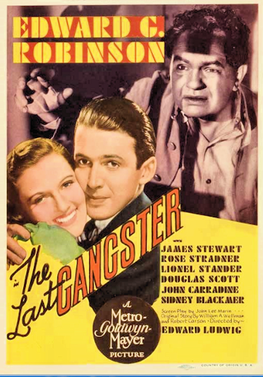

In 1937’s The Last Gangster, Edward G. Robinson plays Al Capone.

Well, actually, that’s not technically true. The character he’s playing is named Joe Krozac. However, Joe is a ruthless killer and gangster. He’s made his fortune through smuggling alcohol during prohibition. Despite his fearsome reputation, Joe is a family man who loves his wife Tayla (Rose Stradner) and who is overjoyed when he learns that she’s pregnant. To top it all off, Joe is eventually arrested for and convicted of tax evasion. He gets sent to Alcatraz, where he finds himself being bullied by another inmate (John Carradine) and waiting for his chance to regain his freedom.

In other words, Edward G. Robinson is playing Al Capone.

Krozac does eventually get out of prison but, by that point, Tayla has moved on. She’s married Paul North (James Stewart), a former tabloid reporter who was so outraged by how his newspaper exploited Tayla’s grief that he resigned his position. Joe Krozac’s son has grown up with the name Paul North, Jr. and he has no idea that his father is actually a notorious gangster.

Krozac wants to get his son back but his gang, now led by Curly (Lionel Stander), has other ideas. They want Krozac to reveal where he hid the money that he made during his gangster days. As well, an old rival (Alan Bazter) not only wants to get revenge on Krovac but also on Krovac’s son. Joe Krovac, fresh out of prison, finds himself torn between getting his revenge on his wife and protecting his son. This being a 30s gangster film, it leads to shoot-outs, car chases, and plenty of hardboiled dialogue.

Edward G. Robinson and Jimmy Stewart in the same movie, how could I n0t watch this!? I was actually a bit disappointed to discover that, even though both Robinson and Stewart give their customarily fine performances, they don’t spend much time acting opposite each other. Indeed, it sometimes seem like the two men are appearing in different pictures.

Robinson is appearing in one of the gangster films that made him famous. (Indeed, the film’s opening credits feature footage that was lifted from some of Robinson’s previous films.) He gives a tough and snarling performance but also one that suggests that, as bad as he is, he’s nowhere near as bad as the other gangsters that are working against him. His gangster is ultimately redeemed by his love for his son, though the Production Code still insists that Joe Krozac has to pay for his life of crime.

Stewart, meanwhile, plays his typical romantic part, portraying Paul as being an incurable optimist, a happy go-getter who still has a sense of right-and-wrong and a conscience. Stewart isn’t in much of the film. This is definitely Robinson’s movie. But still, there’s a genuine charm to the scenes in which Paul romances the distrustful Tayla. Not even being forced to wear a silly mustache (which is the film’s way of letting us know that time has passed) can diminish Stewart’s natural charm.

If you like 30s gangster films, like I do, you should enjoy The Last Gangster. I would have liked it a bit more if Robinson and Stewart had shared more scenes but regardless, this film features these two men doing what they did best. This is an offer that you can’t refuse.