The only reason that I watched the 1974 film, The Driver’s Seat, was because I had heard that Andy Warhol was in it and that he actually played a character other than Andy Warhol.

And that, it turns out, is true. Andy Warhol does appear in The Driver’s Seat. He plays a character known as “The English Lord” and he even attempts to speak with a posh British accent. At the same time, though, it’s hard not to feel that Andy Warhol was still essentially playing himself. Though not lacking in screen presence, Andy played the role with eccentric detachment. It’s stunt casting, which Andy himself probably would have appreciated but, in the larger context of the film, his presence never quite makes sense. Then again, the same can be said about just about every actor in The Driver’s Seat. It’s not a film that’s overly concerned with making sense.

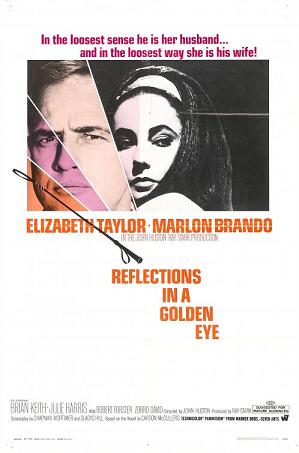

Andy is only in two scenes and they’re both rather short ones. In his first scene, he approaches Lise (played by Elizabeth Taylor) in an airport and hands her a paperback book that she dropped earlier. (The book is called The Walter Syndrome.) As he and his entourage walk away from her, Lise says, “Why is everyone so afraid of me?”

Later on in the movie, Lise runs into the English Lord for a second time. She approaches him and tries to talk to him but, just as before, he doesn’t have much to say to her. He’s deep in conversation with some sort of government minister. At one point, he says, “The King’s an idiot.”

And that’s pretty much the extent of Andy Warhol’s performance.

As for the rest of The Driver’s Seat, it’s one of the many oddly surreal films that Elizabeth Taylor made in the 1970s. Taylor plays Lise, a middle-aged and overweight spinster who goes on an apparently spontaneous trip to Rome. When she’s not trying to flirt with almost every man that she sees, she is obsessing on death. (When she spots a police officer, he asks him if he has a gun and points out that, if he did, he could shoot her right that minute.)

Everyone seems to be scared of Lise, or I should say everyone but Bill (Ian Bannen). Bill is, without a doubt, one of the most annoying characters of all time. When Lise first sees him and his orange tan, she says, “You look like Little Red Riding Hood’s Grandmother. Do you want to eat me?”

Bill laughs and happily replies, “I’d like to, I’d like to. Unfortunately, I’m on a macrobiotic diet and I can’t eat meat.”

Bill’s not joking either. He is obsessed with his macrobiotic diet and won’t shut up about it. He also tells Lise that, as a result of his diet, “I have to have an orgasm a day.”

When I diet, I diet,” Lise replies, “And when I orgasm, I orgasm!” Lise also assures him, “I’m not interested in sex, I’m interested in other things!”

Meanwhile, while all this is going on, random people are getting blown up by terrorists and police officers are chasing young men down in airports. The film is full of flash forwards in which the various characters who have met Lise are roughly interrogated by some sort of shadowy security agency. Interpol, we’re told, is looking for Lise. Everyone is looking for Lise!

Why? Don’t expect an answer. Why doesn’t matter in this film! The Driver’s Seat is one of the most pretentious movies that I’ve ever watched. Fortunately, I have a weakness for pretentious movies from the 1970s. I’ve seen a lot of incoherent movies but I’ve rarely seen one that embraces and celebrates incoherence with quite the enthusiasm of The Driver’s Seat and it’s hard not to respect the film’s determination to be obscure. The movie may make no sense but at least it’s weird enough to be watchable. Elizabeth Taylor actually gives a pretty good performance as Lise, even if you never forget that you’re actually watching Elizabeth Taylor in one of her weird 1970s films. Taylor plays the role with a conviction that sells even the most overwritten and/or obscure piece of dialogue. Add to that, in the 70s, Elizabeth Taylor was probably one of the few people who truly could relate to the situation of having everyone in the world searching for her.

The Driver’s Seat is a pretentious mess and that’s just fine.