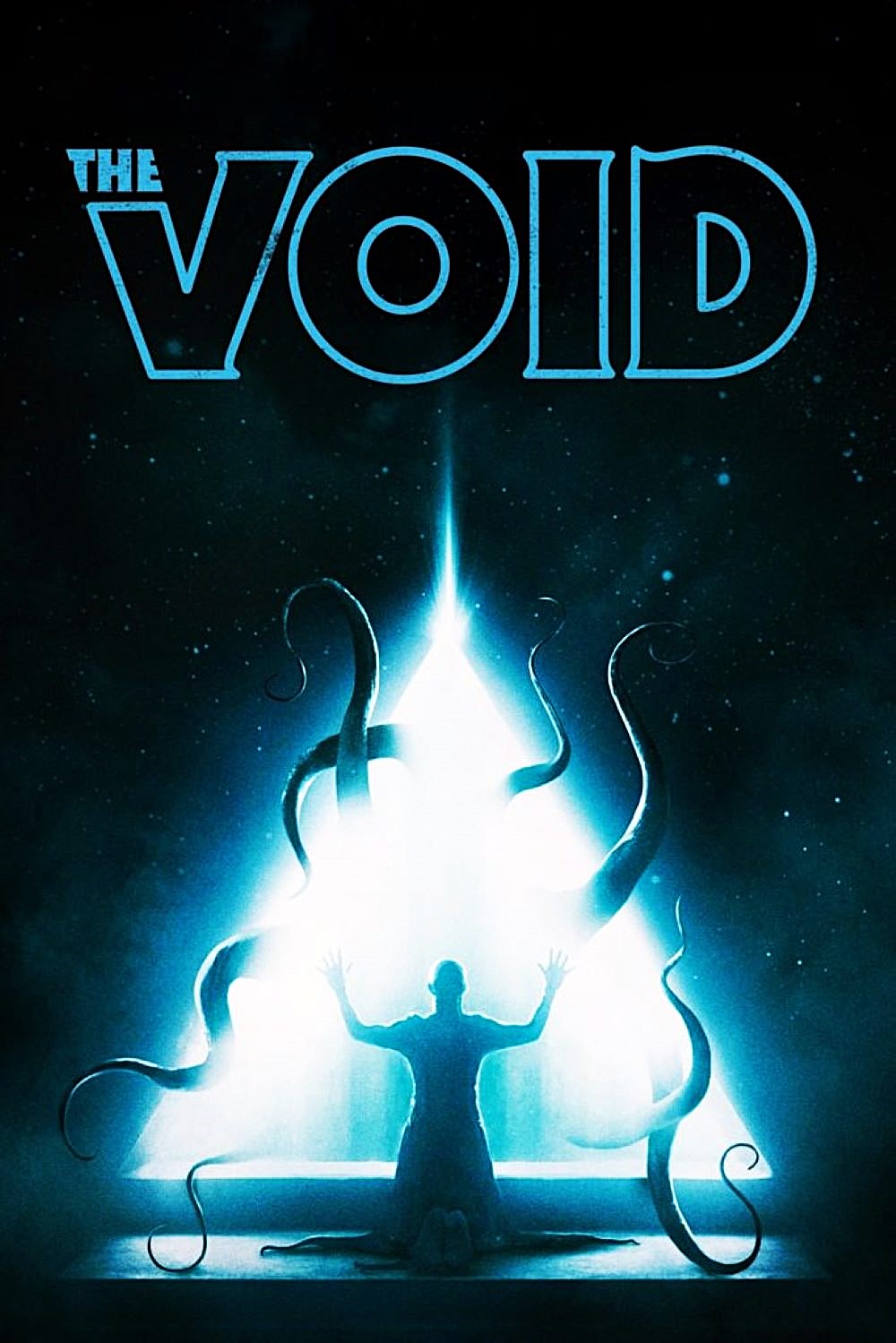

“It’s not just the darkness out there… it’s the darkness in here.” — Sheriff Daniel Carter

Steven Kostanski and Jeremy Gillespie’s The Void is a grisly, atmospheric plunge into Lovecraftian cosmic horror and John Carpenter-inspired body horror, set within a nearly abandoned rural hospital shrouded in eerie blue light and creeping shadows. The film expertly conjures anxiety and dread, as fragile boundaries between dimensions begin to dissolve, threatening to swallow all inside.

At the heart of the story is Deputy Sheriff Daniel Carter (Aaron Poole), whose weighty grief and fractured relationships drive his reluctant heroism. He stumbles upon a bloodied man and brings him to the hospital staffed by his estranged wife, Allison Fraser (Kathleen Munroe), a focused nurse haunted by their broken family. Dr. Richard Powell (Kenneth Welsh) looms as the villainous architect of the unfolding nightmare, his obsession with conquering death fueled by personal tragedy, twisting him into a leader of occult horrors.

The supporting characters—Vincent and Simon, survivors hardened by trauma; Maggie, a pregnant woman caught in the web of cosmic corruption; and Kim, a vulnerable young intern—saturate the siege narrative with survival-driven urgency. Though less developed than the leads, they embody the raw desperation and existential threat pervading the hospital.

The Void wears its influences on its sleeve, drawing heavily from the siege tension of John Carpenter’s Assault on Precinct 13 alongside the paranoia and isolation of The Thing. These classic Carpenter motifs—claustrophobic settings, unrelenting external threat, and mistrust among survivors—penetrate the film’s fabric, amplified by a synthesizer-driven score nodding to Carpenter’s sonic signature. The nightmarish body horror, occult elements, and grotesque practical effects owe much to Stuart Gordon’s work adapting Lovecraft’s stories, blending visceral horror with cosmic dread.

Yet, while the homage is clear and affectionate, the film sometimes falters by blending these iconic elements into a decoction that resists full cohesion. Instead of synthesizing the inspirations into an innovative whole, it assembles a patchwork—rich in style and atmosphere but struggling to commit to a coherent, fresh narrative. The mixture of Carpenter’s claustrophobic siege, Gordon’s visceral mythos, and the cultist horror trope occasionally feels like pastiche rather than a confident new voice.

The technical craftsmanship shines throughout. Practical effects—from mutated creatures to grotesque body transformations—are lovingly crafted and tactile, restoring a physicality often lost in digital horror. The cinematography and lighting accentuate the oppressive mood, favoring muted colors punctuated by blood-red and luminous blues, thinking as much about shadows as solid objects.

However, the film’s narrative and character work often leave something to be desired. While Carter’s arc of guilt and reluctant heroism is thematically resonant, key emotional beats suffer from underdevelopment, with his relationships, particularly with Allison, only superficially explored. Dialogue oscillates between exposition-heavy and clipped, hindering audience connection with the cast amid the unrelenting terror. The supporting characters serve primarily functional roles, their deeper motivations and backstories sacrificed for the sake of grim spectacle and escalating horror.

The climax descends into surreal, fragmented sequences that evoke fever dreams more than narrative resolution. This abstract finale, while visually striking, challenges viewers seeking clarity and can be polarizing: some will appreciate the cosmic horror tradition of unsolvable mysteries, while others may experience frustration with the loose plotting and ambiguity. Pacing reflects these shifts—building steadily in the opening act before devolving into frenetic, disjointed bursts that occasionally undermine tension.

Despite these narrative and pacing flaws, The Void remains a memorable experience for lovers of practical effects and cosmic horror texture. It’s a film rich with unsettling imagery and mood, capturing a form of existential terror that goes beyond cheap scares. The filmmakers’ love for classic horror runs deep, even if the resulting fusion occasionally feels like homage without full reinvention.

Ultimately, The Void is a dark, unsettling trip into the unknowable—a sonic and visual descent into a hellish siege where logic unravels and time shatters. It’s a film that prizes atmosphere and physical monstrosity over smooth storytelling, inviting viewers to surrender to dread rather than demand explanation. For fans of Carpenter’s minimalist tension, Gordon’s visceral adaptations, and the tactile nightmares of 80s horror, The Void offers a rewarding, though imperfect, journey into the cosmic abyss—an evocative invocation of terror where humanity is both survivor and prey.