I like The Doors.

That can be a dangerous thing to admit, about both the band and Oliver Stone’s 1991 film. Yes, both the band and the film could be a bit pretentious. They both tended to go on for a bit longer than necessary. They were both centered around a guy who wrote the type of poetry that I used to love back in my emo days. It’s all true.

But, with The Doors as a band, I find that I can’t stop listening to them once I start. Even if I might roll my eyes at some of the lyrics or if I might privately question whether any blues song really needs an organ solo, I can’t help but love the band. They had a sound that was uniquely their own, a psychedelic carnival that brought to mind images of people dancing joyfully while the world burned around them. And say what you will about Jim Morrison as a poet or even a thinker, he had a good voice. He had the perfect voice for The Doors and their rather portentous style. From the clips that I’ve seen of him performing, Morrison definitely had a stage presence. Morrison died young. He was only 27 and, in the popular imagination, he will always look like he’s 27. Unlike his contemporaries who managed to survive the 60s, Morrison will always eternally be long-haired and full of life.

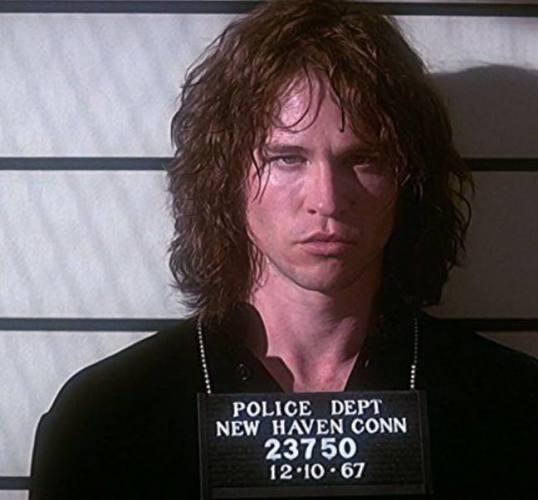

As for The Doors as a movie, it’s definitely an Oliver Stone film. It’s big. It’s colorful. It’s deliberately messy. Moments of genuinely clever filmmaking and breath-taking visuals are mixed with scenes that are so heavy-handed that you’ll be inspired to roll your eyes as dramatically as you’ve ever rolled them. Stone loved the music and that love comes through in every performance scene. Stone also loves using Native Americans as symbols and that can feel a bit cringey at times. Why would Jim Morrison, whose was of Scottish and Irish ancestry, even have a Native American spirit guide? At its best The Doors captures the chaos of a world that it’s the middle of being rebuilt. The 60s were a turbulent time and The Doors is a turbulent movie. I’ve read many reviews that criticized The Doors for the scene in which Morrison gets involved in a black magic ceremony with a journalist played by Kathleen Quinlan. I have no idea whether or not that scene happened in real life but the movie is so full of energy and wild imagery that the scene feels like it belongs, regardless of whether it’s true or not. Stone turns Jim Morrison into the warrior-artist-priest that Morrison apparently believed himself to be and the fact that the film actually succeeds has far more to do with Oliver Stone’s enthusiastic, no-holds-barred direction and Val Kilmer’s charismatic lead performance than it does with Jim Morrison himself.

The Doors spent several years in development and there were several actors who, at one time or another, wanted to play Morrison. Everyone from Tom Cruise to John Travolta to Richard Gere to Bono was considered for the role. (Bono as Jim Morrison, what fresh Hell would that have been?) Ultimately, Oliver Stone went with Val Kilmer for the role and Kilmer gives a larger-than-life performance as Morrison, capturing the charisma of a rock star but also the troubled and self-destructive soul of someone convinced that he was destined to die young. Kilmer has so much charisma that you’re willing to put up with all the talk about opening the doors of perception and achieving a higher consciousness. Kilmer was also smart enough to find the little moments to let the viewer know that Morrison, for all of his flamboyance, was ultimately a human being. When Kilmer-as-Morrison winks while singing one particularly portentous lyric, it’s a moment of self-awareness that the film very much needs.

(When the news of Kilmer’s death was announced last night, many people online immediately started talking about Tombstone, Top Gun, and Top Secret. For his part, Kilmer often said he was proudest of his performance as Jim Morrison.)

In the end, The Doors is less about the reality of the 60s and Jim Morrison and more about the way that we like to imagine the 60s and Jim Morrison as being. It’s a nonstop carnival, full of familiar faces like Kyle MacLachlan, Michael Madsen, Crispin Glover (as Andy Warhol), Frank Whaley, Kevin Dillon, and a seriously miscast Meg Ryan. It’s a big and sprawling film, one that is sometimes a bit too big for its own good but which is held together by both Stone’s shameless visuals and Val Kilmer’s charisma. If you didn’t like the band before you watched this movie, you probably still won’t like them. But, much like the band itself, The Doors is hard to ignore.