2009 will probably go down as the year James Cameron returned from a self-imposed exile from feature-lenght filmmaking. It has been 12 years since his last major film for a big Hollywood studio. Titanic became the all-time box-office king with Cameron winning accolades and awards for his efforts. He was no flushed with money which has allowed him to take a break from making films audiences have come to expect from him. Instead he decided to go back to his first true-love growing up in Chippewa, Canada. Cameron went exploring the deepest parts of the ocean not just as a filmmaker but a scientists, researcher and explorer. This time of his life after proclaiming himself “King of the World” in the 1998 Academy Awards shows the dichotomy of James Cameron’s life and personality: the artist and scientist in one body.

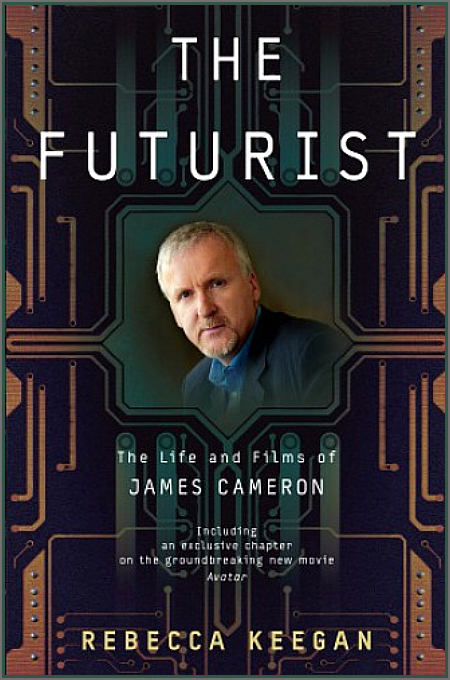

It is the task of Rebecca Keegan’s biography of this modern-day renaissance man to give an insight as to how the two sides of Cameron made him the success he is today and one of the pioneers in filmmaking. The Futurist will look back to his childhood and, with unprecedented access to Cameron’s family, close friends, associates and, best of all, James Cameron himself, show us a glimpse at the very reclusive filmmaker. The book doesn’t overly fawn over Cameron’s talents and achievements, but if there was a man deserving such attention it would be Cameron. Keegan never really points out and concentrate on the negatives of Cameron’s life and personality, but does allow these traits to show how committed and focused an individual Cameron was when it came to his work and demanded nothing less from those who worked with him.

The book details how Cameron’s parents may have had a major influence in how he turned out in life. Born of a father who was a mechanical engineer and an artist of a mother with a self-reliance and powerful personality which would imprint the young Cameron at an early age. In fact, Keegan devotes the early sections of the book to showing how gifted the Cameron brood was from Jim’s parents to his four other siblings. But in the end, it was Cameron who was the take-charge of the litter. Even at an early age it was he who led the other kids on his projects (which included building a plane from scraps and junk around the neighborhood). Right from the beginning Keegan was able to show us the many experiences and influences that both lead to him being one of the world’s foremost filmmakers to one also renowned for his dictatorial-style on the film set.

The Futurist really offers just a glimpse on the life of Cameron. It is a life that could almost be a primer for all young people dreaming to be filmmakers themselves or just whatever they want to do in life with something they love. Keegan’s casual writing style doesn’t have the dry, academic tone of most biographies. She almost treats the biography’s many chapters as a behind-the-scenes look into every film project Cameron has been a part of. From his early days as model builder in Roger Corman’s New World Pictures right up to his latest project for 20th Century Fox, Avatar. While each film discussed was already quite interesting for a fan of the filmmaker and those films, I was even more interested in finding out how Cameron’s own dedication and laser-like focus on each project showed both the genius and madman aspect of the man. Here was an individual so intelligent that he could converse with artists and scientists and keep up, if not, hold his own.

One specific anecdote in the biography which shows a lot about Cameron as a modern renaissance man was his time between Titanic and Avatar. This was a part of Cameron’s life where the scientist in him took precedence. He was working on a Mars film project and had come to work with NASA engineers and scientists on future plans to try and reach the Red Planet. Having access to unofficial papers and technical papers on such a project, Cameron was able to come up with a hybrid Mars lander which would also double as the rover. He submitted the plans and design specs to this “lander rover” to the NASA team who ended up more than impressed. A similar-looking lander rover would soon land on a later Mars mission and all thanks to the outside the box thinking Cameron was able to add to the scientists who had been working for years on the project. One of the NASA engineers was so impressed that he was heard to have commented that if Cameron wasn’t a filmmaker he definitely would’ve turned out to be an exceptional engineer.

It’s that admiration from those who have worked with Cameron which comes up more than once in Keegan’s book. She shows not just his artistic side but his love of science and research. Cameron definitely comes off as the know-it-all in the room. Whether one sees that as a negative or a positive it doesn’t change the fact that he probably does know it all and do it better than most in a room of contemporaries. We learn from Keegan’s inside-look at Cameron’s life how he could easily be a one-man film set. Most filmmakers, even great ones, rarely pick up a camera or become a major part of the editing process. Cameron could do everything that needs to be done on a set minus the acting. The Futurist also goes to great lenghts to point out that while Cameron was great at pretty much anything the needs to be done to make a film as a writer he admits to her how much he struggles at it. He sees the writing side of the film equation as something he wished he could do better and always trying to improve at it. This goes towards the many criticisms about Cameron’s film being cardboard cutouts of stories already done and done better. It goes to explain Cameron’s need to control every aspect of his film projects that he only trusts himself and, maybe close friends, to write the script for his films.

He wants to film his stories, his ideas and not other people. It definitely shows how many in Hollywood could equate that with him being very egocentric in how he deals with his peers. Some may admire this trait and others may see it as a man over his head and banking on the simple taste of the general population to make his films succeed. While I do not subscribe to the latter, I do think that much of the backlash he has received with his last two films go back to his ego and superiority over others. It is not easy for people who think they know what they talk about when it comes to film and everything that goes in making one be made to feel stupid when he makes it known. But then he has made a habit of being vindicated in the end despite these trait flaws. As the saying goes, “Sometimes the truth hurt.” James Cameron definitely comes across in the book as a no-nonsense, bullshit-free dictator who is smarter than everyone else.

In the end, Rebecca Keegan’s The Futurist is an engaging look-inside the mind of the man who has proclaimed himself “King of the World” and who others have called under their breath as a tyrannical dictator of a filmmaker. While the book could’ve been much longer and gone into even more detail about Cameron, his life and his films Keegan has definitely laid down the groundwork on any future Cameron biographies both official and unofficial. There’s definitely more to learn about this unique blending of romantic artists and dedicated science genius in one mind and body. For fans of James Cameron this book is definitely a must-have and read. For those just wanting to know more about this pioneer filmmaker then this book is a great primer to learning more about him.