4 Or More Shots From 4 Or More Films is just what it says it is, 4 shots from 4 of our favorite films. As opposed to the reviews and recaps that we usually post, 4 Shots From 4 Films lets the visuals do the talking!

4 Shots From 4 Fantasy Films

4 Or More Shots From 4 Or More Films is just what it says it is, 4 shots from 4 of our favorite films. As opposed to the reviews and recaps that we usually post, 4 Shots From 4 Films lets the visuals do the talking!

4 Shots From 4 Fantasy Films

4 Or More Shots From 4 Or More Films is just what it says it is, 4 shots from 4 of our favorite films. As opposed to the reviews and recaps that we usually post, 4 Shots From 4 Films lets the visuals do the talking!

Today, we pay tribute to the year 1975. It’s time for….

4 Shots From 4 1975 Films

Though the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences claim that the Oscars honor the best of the year, we all know that there are always worthy films and performances that end up getting overlooked. Sometimes, it’s because the competition too fierce. Sometimes, it’s because the film itself was too controversial. Often, it’s just a case of a film’s quality not being fully recognized until years after its initial released. This series of reviews takes a look at the films and performances that should have been nominated but were,for whatever reason, overlooked. These are the Unnominated.

Really, Academy?

No nominations for one of the most influential and widely-quoted films ever to be released?

Well, actually, I get it. Monty Python and the Holy Grail was first released in 1975 and 1975 was an unusually good year for cinema. Back in the 70s, of course, the Academy only nominated five films for Best Picture and, as a result, a lot of good films were not nominated that year. There just wasn’t room for them. Check out the five films that were nominated and ask yourself which one you would drop to make room for a different nominee.

Would you drop:

Barry Lyndon, which was directed by Stanley Kubrick was considered to be the most realistic recreation of the 18th Century to ever be captured on film,

Dog Day Afternoon, in which director Sidney Lumet brilliantly mixed comedy and drama and which featured wonderful performances from Al Pacino, John Cazale, Chris Sarandon, and Charles Durning,

Jaws, the Steven Spielberg-directed hit that changed the face of Hollywood,

Nashville, Robert Altman’s sprawling and ambitious portrait of a country tying to find itself after a decade of trauma,

or

One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, in which Milos Forman paid tribute to individual freedom and Jack Nicholson gave perhaps the best performance of his legendary career?

I mean, those are five great films. Even the weakest of the nominees (which, in this case, I think would be the eventual winner, One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest) is still stronger than the average Best Picture nominee.

So, I can understand why there wasn’t room for an episodic and rather anarchistic British comedy, one that largely existed to parody the type of epic and period filmmaking that the Academy tended to honor. If there had been ten nominees in 1975 and Monty Python and the Holy Grail had been snubbed to make room for something like The Other Side of the Mountain, my feelings might be different but there weren’t.

That said, even if there wasn’t room in the Best Picture slate, what to make of the lack of nominations for a script that is so full of quotable lines and memorable incidents that even people who haven’t seen Monty Python and the Holy Grail are familiar with them? No nominations for the costumes, the production design, or the cinematography, all of which are surprisingly good for a low-budget film that was directed by not one but two untested neophyte directors? No nominations for the thrilling music or the Camelot song? How about a special award for the killer rabbit?

How about at least a best actor nomination for Graham Chapman, who played King Arthur not as a comedic buffoon but instead as being well-intentioned but also increasingly frustrated by the fact that his subjects cared not about his quest or his royal title? Though 1975 may have been a strong year for movies, it appears that the Academy still struggled to find five best actor nominees and they resorted to giving a nomination for James Whitmore’s performance as Harry Truman in a filmed version of his one-man stage show, Give ‘Em Hell Harry. Nothing against James Whitmore or Harry Truman but I think we all know that spot belonged to Graham Chapman and his performance as King Arthur.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail is often described as being a satire of the Arthurian legends. I think, even more than being a film about King Arthur, it’s a film about a group of people trying to make an epic despite not having the resources or the patience to do so. Python humor has always featured characters who were both foolishly confident and stubbornly aggressive and both of those traits are on wide display in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. The production can’t afford horses so Arthur and his knights hit two coconuts together to duplicate the sound of the hooves on the ground and when they’re confronted about it, they attempt to change the subject. Can’t afford to shoot in a real castle? Simply declare Camelot to be a silly place and walk away. Can’t afford to get permits to film on a certain location? Film illegally and run the risk of getting arrested just when you’re about to start the film’s climatic battle scene. Can’t afford to hire God for a cameo? Use a cut-out. Can’t afford a real knight? Just hire some people who get carried away and then hope one of them doesn’t kill the local academic who has shown up to explain the film’s historical context.

“I just get carried away,” John Cleese’s Lancelot says more than once and he has a point. But the entire movie is about people getting carried away. The Black Knight is so carried away in his belief in himself that he continues to fight despite having neither arms nor legs. The villagers are so carried away in their desire to burn a witch that they cheer when it’s discovered that she weighs the same amount as a duck. (“It’s a fair cop,” the witch, played by Connie Booth, admits.) Eric Idle’s Sir Robin is so carried away in his ability to answer questions that he doesn’t consider that he might be asked about the capitol of Assyria. The Knights of the Round Table as so carried away in their dancing and their singing that no one wants to go to the castle. Even the film’s animator gets carried away, suffering a heart attack and saving Arthur and his surviving knights from a fate worse than death.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail is a very funny film, of course. We all know that. (I once read a story about a woman who, having learned she only had a few weeks to live, decided to watch this film everyday until she passed. I don’t blame her.) But what I truly love about this film is that, in scene-after-scene, you can literally see the Pythons realizing that they were actually capable of making a real movie. Michael Palin, especially, seems to be having so much fun playing the eternally pure Sir Galahad that it’s impossible not to get caught up in his happiness. There’s a joie de vivre that runs through Monty Python and the Holy Grail, even at its darkest and most cynical. The Pythons are having fun and it’s impossible not to have fun with him.

And, while the Oscars may have snubbed Monty Python and the Holy Grail, the Tonys did not. When the film was later turned into Spamalot, it received 14 Tony nominations and won three.

Previous entries in The Unnominated:

A tall, dark-haired British man sits behind a desk that is rather oddly sitting in the middle of a field. He wears a dark suit and he looks quite serious as he says, “And now, for something completely different….”

Cut to a short film about a man with a tape recorder up his nose, followed by another short film about man who has a tape recorder up his brother’s nose.

A Hungarian man tries to buy cigarettes while using an inaccurate English phrasebook. The publisher of the phrasebook is later brought before the court.

Poor old Arthur Pewty goes to marriage counseling and can only watch impotently as the counselor seduces his wife. Having filed to stand up for himself, Pewty is crushed by 16-ton weight.

A self-defense instructor teaches his students how to defend themselves when they are attacked by a man with a banana.

A loquacious man in a pub says “nude nudge” and “wink wink” until his drinking companion is finally forced to slam down his drink.

A man who sees double recruits a mountaineer to climb the two peaks of Mt. Kilimanjaro. Hopefully, they’ll be able to find last year’s expedition, which was planning on building a bridge between the two peaks.

There’s bizarre, almost Dadaist animation, featuring classic works of art interacting with cartoonish cut-outs.

Uncle Sam appears to explain how communism is like tooth decay. A toothpase commercial explains how taking care of your teeth is like racing a car. A motor oil company shows how it can destroy darkness and grim.

A prince dies of cancer but the spot on his face flourishes until it falls in love and moves into a housing development.

A man tries to return a dead pigeon. The store clerk insists the pigeon is merely stunned and then sings about wanting to be a lumberjack.

A general complains that things have gotten much too silly.

The narrator appears randomly, announcing, “And now for something completely different….”

Okay, okay, you get the idea. First released in 1971, And Now For Something Completely Different was the first film to be made featuring all of the members of Monty Python’s Flying Circus. It was their initial attempt to break into the American market, a collection of surreal sketches that they had previously performed on television for the BBC. Unfortunately, at the time, no one in America really knew who Monty Python was and the film failed at the box office, to the extent that many in the UK advised against Monty Python even allowing their program to later air on PBS because it was felt that Americans just wouldn’t get it. Of course, Americans did eventually get it. The show remains popular to this very day. Countless Americans are convinced that they can speak in a perfectly convincing British accent, as long as they’re quoting a line from Monty Python. The previous 4th of July, when the town band played John Philip Sousa’s Liberty Bell, I saw hundreds of people stamping down their feet at the end of it. As for And Now For Something Completely Different, it was re-released in 1974 and became a bit of a cult favorite in the States.

That said, the members of Monty Python were never particularly happy with the film. They were convinced to make the film by Victor Lownes, who was the head of Playboy’s UK operation. Lownes, however, alienated the members of the group by trying to exert control over the material. He particularly objected to the character of Ken Shabby, a perv who probably had a stash of sticky Playboys back at this flat. Lownes also put up very little money for the production, meaning that the Pythons had to resort to shooting the film, without an audience, in a deserted factory. Apparently, even the deliberately cheap-looking special effects of the television show were considered to be too expensive to recreate for the film. Michael Palin and Terry Jones both later complained that the film itself was series of scenes featuring people telling jokes while sitting behind desks.

Of course, Lownes’s biggest sin was trying to insinuate that he was somehow the Seventh Python. (One can only imagine how many people were guilty of the sin over the years. Claiming to be the Seventh Python was probably a bit like claiming to be the Fifth Beatle.) When Terry Gilliam was animating the film’s opening credits, the names of the cast were shown in blocks of stone. Lownes insisted that his name by listed the same way. Gilliam reluctantly acquiesced but then redid the names of the Pythons so that they were no longer in stone. Fortunately, Victor Lownes would not involved in the subsequent Python films.

All that said, there’s no denying that And Now For Something Completely Different is a funny movie. I mean, it’s Monty Python. It’s John Cleese, Michael Palin, Graham Chapman, Eric Idle, Terry Jones and Terry Gilliam, all youthful and at the heights of their considerable comedic talents. Even if all of the sketches are familiar from the show, they’re still funny and it’s impossible not to enjoy discovering the way that the movie threads them together. (Combining the Lumberjack song with the dead parrot sketch worked out brilliantly. “What about my bloody parrot!?” Cleese is heard to shout as Palin walks through the forests of British Columbia.) Personally, my favorite Python is Eric Idle but I also love any sketch that involves Michael Palin getting on John Cleese’s nerves. Everyone knows the dead parrot sketch, of course. But I also like the vocational guidance counselor sketch. It’s hard not to get caught up in Palin’s excitement as he discusses his lion tamer’s hat. Almost as wonderful as Palin’s turn as Herbert Anchovy, accountant was Michael Palin’s turn as the smarmy host of Blackmail. Actually, maybe Michael Palin is my favorite Python. I guess it’s a tie between him and Eric.

And Now For Something Different has been on my DVR for quite some time. I’ve watched it several times. I’m not planning on deleting it any time soon.

4 Shots From 4 Films is just what it says it is, 4 shots from 4 of our favorite films. As opposed to the reviews and recaps that we usually post, 4 Shots From 4 Films lets the visuals do the talking!

Today would have been the 77th birthday of my favorite members of the Beatles (not to mention The Traveling Wilburys), George Harrison. Harrison died far too young but he left behind a legacy of music that is celebrated to this day and will still be celebrated long after the rest of us have moved on.

While everyone knows George from his music, what is often forgotten is that Harrison is also often credited with helping to revive the British film industry. After the break-up of the Beatles, Harrison partnered with Denis O’Brien and formed HandMade Films. At a time when British cinema was struggling both financially and artistically, Harrison served as executive producer for some of the best films to come out of the British film industry. Harrison championed many talented British directors and he used his clout to get many otherwise difficult project produced. It’s fair to say that, if not for his support, the members of Monty Python would never have been able to make the then-controversial Life of Brian, which is now widely regarded as one of the best British comedies ever made.

Today, on his birthday, here are four shots of four films executive produced by George Harrison.

4 Shots From 4 Films

I just heard the incredibly sad news that Terry Jones has died. Jones, who was one of the founders of Monty Python and a respected medieval scholar, was 77 years old. It was announced three years ago that Jones was suffering from a rare form of dementia so his death was not unexpected but it still hurts.

When I was a kid and I was watching Monty Python’s Flying Circus for the first time, I initially did not fully appreciated Terry Jones. I liked him because I liked every member of Monty Python and every British comedy fan grows up wishing that they could have been a member of the group. (My favorite was Eric Idle.) But it was sometimes easy to overlook Terry Jones’s performance on the show because his characters were rarely as flamboyant as some of the other ones. He was never as grumpy as John Cleese nor was he as sarcastic as Eric Idle. Michael Palin (who was Jones’s writing partner long before the two of them become members of Monty Python) cornered the market on both unctuous hosts and passive aggressive countermen. Meanwhile, Graham Chapman played most of the upright authority figures and Terry Gilliam provided animation. Terry Jones, meanwhile, often played screeching women and bobbies who said, “What’s all this then?”

It was only as I got older and I came to better appreciate the hard work that goes into being funny that I came to appreciate Terry Jones and his ability to always nail the perfect reaction to whatever lunacy was occurring around him. It was also as I got older that I started to learn about the origins of Monty Python and what went on behind the scenes. I learned that Terry Jones was a key player. Along with writing some of Monty Python‘s most memorable material, he also directed or co-directed their films. On the sets of Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Life of Brian, and The Meaning of Life, Jones provided the structure that kept those films from just devolving into a collection of skits.

Unlike the other members of Monty Python, Terry Jones never really went out of his way to establish an acting career outside of the group. Instead, he wrote screenplays and serious books on both medieval history and Geoffrey Chaucer. Appropriately, for a member of the troupe that changed the face of comedy, Jones often challenged the conventional views of history. Terry Jones was the only man in Britain brave enough to defend the Barbarians.

On the last day of the ninth grade, my English teacher, Mr. Davis, rewarded us for our hard work by showing us what he said was the funniest scene in film history. The scene that he showed us came from the Terry Jones-directed Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life and it featured Jones giving a literally explosive performance as Mr. Creosote.

With thanks to both Mr. Davis and Terry Jones:

Terry Jones, Rest in Peace.

4 Shots From 4 Films is just what it says it is, 4 shots from 4 of our favorite films. As opposed to the reviews and recaps that we usually post, 4 Shots From 4 Films is all about letting the visuals do the talking.

In 1978, George Harrison co-founded HandMade Films to finance Monty Python’s The Life of Brian. The company continued to produce films through the 80s and helped to reinvigorate the British film industry. All of the shots below come from HandMade films and credit George Harrison as executive producer.

4 Shots From 4 Films

Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979, directed by Terry Jones)

Time Bandits (1981, directed by Terry Gilliam)

Mona Lisa (1986, directed by Neil Jordan)

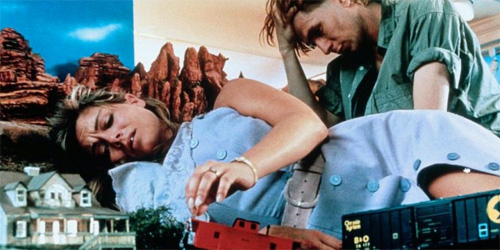

Track 29 (1988, directed by Nicolas Roeg)