“Memories… memories are not to be toyed with!” — Heinz

Memories is a mid‑90s anime anthology that feels like a snapshot of how wild and experimental the medium could be when a bunch of heavy hitters got to play in the same sandbox. It’s made up of three separate stories—“Magnetic Rose,” “Stink Bomb,” and “Cannon Fodder”—that don’t connect plot-wise but circle around similar ideas: how technology intersects with memory, systems, and human weakness. The end result is uneven in spots but consistently interesting, and when it clicks, it’s honestly outstanding.

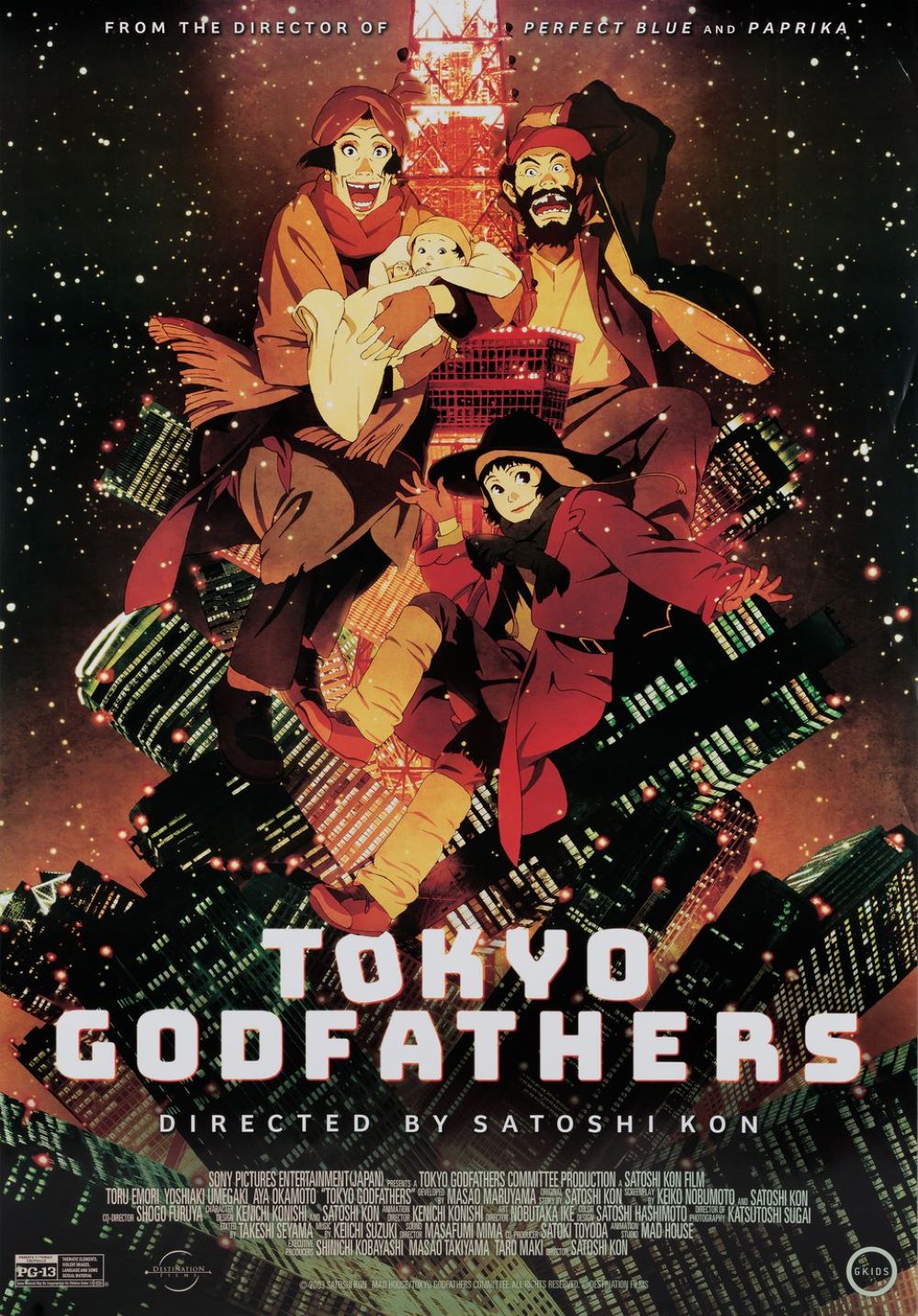

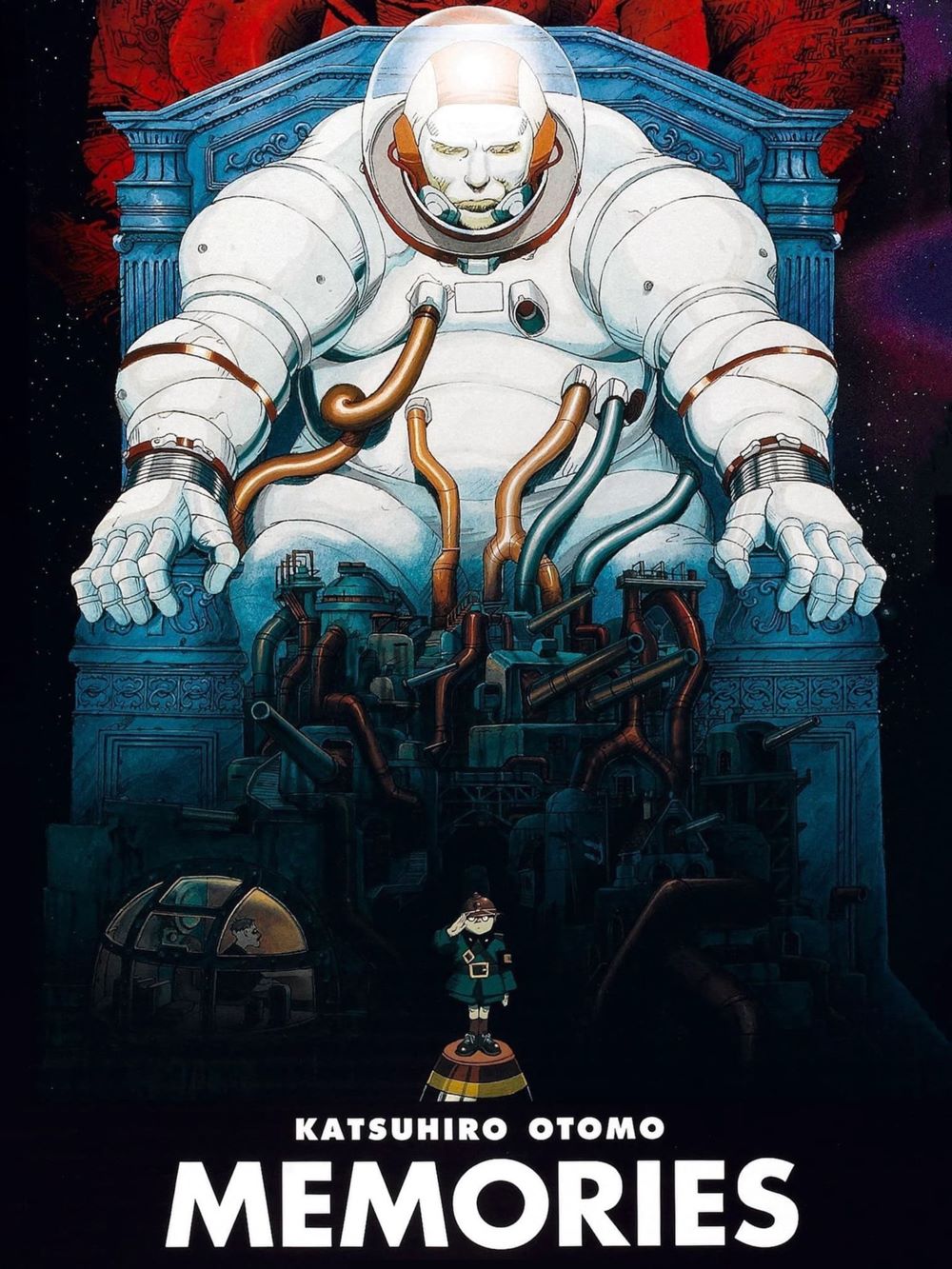

“Magnetic Rose” is the clear showpiece. Directed by Kōji Morimoto and written by Satoshi Kon, it follows a deep-space salvage crew that investigates a distress signal and discovers a derelict structure haunted by the lingering memories of a famous opera singer. The visual approach blends cold, utilitarian sci‑fi hardware with crumbling, ornate interiors, so it feels like the crew is trespassing inside someone’s decaying mind as much as an abandoned ship. The way the environment morphs and lies to the characters, folding past and present together, already hints at the kind of reality‑slipping storytelling Kon would later become famous for.

The sound design and score really push this one over the top. Yoko Kanno leans into big, emotional, opera‑flavored cues that give the segment a tragic, almost theatrical sweep rather than just standard genre tension. Instead of simply backing up jump scares or space thrills, the music amplifies the grief and obsession at the heart of the story, so it plays less like straightforward sci‑fi horror and more like a ghost story built out of longing and denial. The characters themselves are drawn pretty broadly—they mostly function as recognizable types (the seasoned veteran, the younger hothead, the crew just doing their job) rather than deep, fully explored people—but that simplicity keeps the short moving and leaves room for the atmosphere to breathe. In practice, the combination of visuals, sound, and escalating psychological pressure makes “Magnetic Rose” feel rich and layered even without a lot of explicit character backstory.

After that, Memories swerves sharply into “Stink Bomb,” a dark comedy directed by Tensai Okamura. The premise is almost absurd on its face: a lab worker accidentally turns himself into a walking biohazard and slowly becomes the epicenter of a massive crisis. The tone is much lighter, even cartoonish, but there’s a sharp satirical edge underneath. Most of the jokes come from watching institutional systems totally fail to understand or handle what’s happening, ramping up their response in increasingly overblown ways while the poor guy at the center of it all has no idea how dangerous he’s become. It’s a fun, briskly paced piece that lets the animators go wild with chaos and destruction.

That said, “Stink Bomb” is also the segment that feels the most limited conceptually. Once the central gag is in place—this one ordinary guy unintentionally leaving disaster in his wake while officials keep making things worse—the short mostly riffs on variations of that idea. The animation stays lively and the satire lands, and there are flashes of real bite in how it portrays bureaucracy and military decision‑making. But compared to the emotional and thematic density of “Magnetic Rose” or the chilling world‑building of “Cannon Fodder,” it leaves less to chew on once the credits roll. It’s enjoyable, just not as haunting.

“Cannon Fodder,” directed by Katsuhiro Otomo himself, is the quietest but in some ways the most unsettling of the three. It takes place in a city whose entire existence revolves around firing gigantic cannons at an enemy no one ever actually sees. Everything—from education to labor to family routines—is oriented toward that single, unexamined purpose. Visually, it stands apart from the rest of the film: the designs are rougher and more stylized, drawing on European comic and industrial influences rather than sleek anime polish. The big stylistic flex is the way the segment is staged to feel like one continuous movement, with the “camera” drifting through streets, factories, and cramped apartments, watching people go through their day.

There isn’t much conventional plot here, and that’s intentional. The story follows workers and a single family long enough to show how thoroughly the ideology of constant war has soaked into everyday life. Kids learn artillery math at school; adults talk about shell trajectories like it’s the weather. Because the short avoids big twists or overt exposition, it hits more like a living political cartoon: the point is how normalized the whole nightmare has become. Some viewers might find the slower, observational rhythm a bit dry or abstract, especially coming after two more immediately engaging segments. But if the mood clicks, “Cannon Fodder” leaves a lingering, uneasy aftertaste that fits the anthology’s preoccupation with systems and dehumanization.

Stepping back, the three shorts show off just how flexible this medium can be. You get operatic space horror, satirical disaster comedy, and austere anti‑war parable in a single package. There is no explicit framing device tying them together, and the shifts in tone are dramatic, so the film doesn’t feel “smooth” in the way a more unified narrative would. That can be a downside if you’re expecting a cohesive movie rather than a curated set of pieces. On the other hand, that variety is a big part of the appeal: each segment has its own personality and agenda, and the anthology structure lets them coexist without compromise.

On a technical level, Memories holds up surprisingly well. The hand‑drawn animation retains a level of texture and physicality that still looks great today, and the layouts and background work in all three segments are consistently strong. “Magnetic Rose” in particular could be screened alongside other top‑tier anime films from the era and not feel out of place. “Cannon Fodder” still feels formally bold because of its faux‑continuous-shot approach and its distinct visual tone. If anything has aged, it’s more about pacing—modern viewers used to ultra‑fast editing and constant exposition might find some stretches slower than expected—but the film rewards anyone willing to lean into its rhythms.

In terms of accessibility, Memories isn’t the most beginner‑friendly anime film. The first segment leans into psychological horror and tragedy, which can be intense if you’re mostly used to lighter or more straightforward sci‑fi. The comedic whiplash of “Stink Bomb” right after might feel tonally off if you’re still processing the emotional punch of “Magnetic Rose.” And “Cannon Fodder” asks you to be okay with a more metaphor‑driven, open‑ended piece rather than a neatly resolved story. That mix means the anthology is more likely to resonate with viewers who are already interested in anime as a cinematic form and are curious to see different approaches pushed side by side.

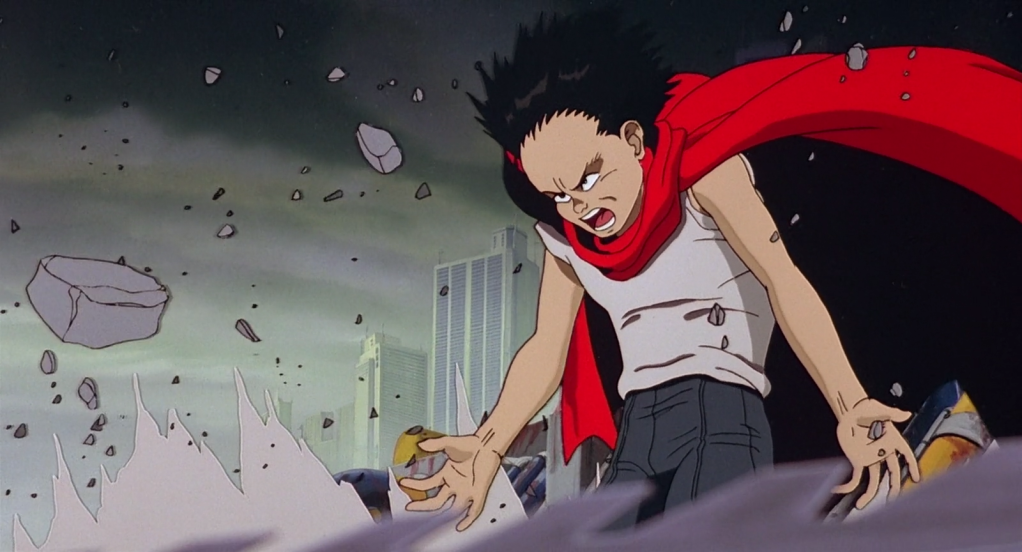

What really makes Memories feel important, though, is the cluster of talent involved and what they went on to do. Katsuhiro Otomo brings the weight of Akira and uses this film as a space to experiment with scale and structure. Kōji Morimoto’s work here sits right in the trajectory of his later, more explicitly experimental projects. Satoshi Kon’s script for “Magnetic Rose” reads almost like a prototype for the identity‑fracturing stories he’d later build entire films around. Tensai Okamura and Yoshiaki Kawajiri bring a sensibility for action and genre that gives “Stink Bomb” its bite, and Yoko Kanno is already showing the range and emotional intelligence that would make her one of anime’s most beloved composers. Even if you stripped away the historical context, the film would still be worth watching—but knowing what these creators went on to do makes it feel like catching a moment just before a lot of big ideas fully explode.

Taken as a whole, Memories plays like a compact tour through different corners of what anime could do in the 1990s when it wasn’t worried about franchising or playing it safe. It’s not flawless, and not every segment will work equally well for every viewer, but the high points are strong enough that the anthology earns its reputation. For anyone interested in the evolution of anime as an art form—especially on the sci‑fi and psychological side—it’s absolutely worth the time, both as a film in its own right and as a window into a formative creative era.