Directed by Andy Warhol, 1964’s Soap Opera features a plot that largely plays out in silence.

The silent, grainy black-and-white footage depicts what appears to be a love triangle between Warhol associate Rufus Collins, Sam Green, Ivy Nicholson, Gerard Malanga, and “Baby Jane” Holzer. There’s a lot of kissing. There’s a lot of slapping. There’s a lot of scenes of our nameless characters giving each other suspicious and meaningful looks. At one point, Jane Holzer makes what appears to be a very important phone call. We don’t know who these people are or how they’re related but they certainly do seem to be intensely obsessed with each other. The situations grow progressively more and more sexual and one gets the feeling that, if we could only hear the dialogue, we would have a chance to vicariously take part in a great melodrama. Of course, the footage itself is so grainy that it’s sometimes hard to tell who is who. Indeed, the characters often seem to be interchangeable. That’s certainly true of real soap operas as well. With new actors regularly stepping into old roles and one story’s hero becoming the next story’s villain, soap operas were all about accepting whatever was presented on the screen. In real life, drama has real consequences. In Warhol’s film and on television, melodrama is just something that happens without any real repercussions.

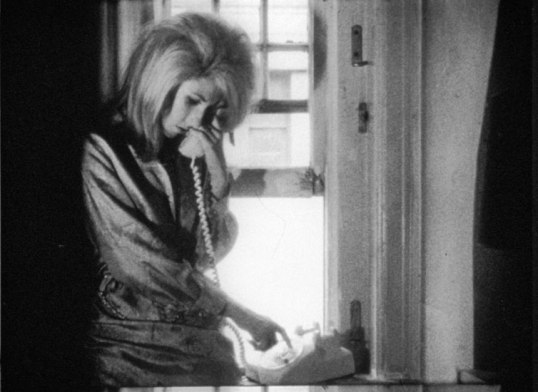

Fortunately, the film provides a few breaks from the repetitive cycle of nonstop, grainy drama. Sprinkled throughout the film are commercials breaks, featuring actual commercials that were supplied to Warhol by Lester Persky, an advertising executive who later found greater fame as a Broadway producer. (He produced Hair, amongst other productions.) In between scenes of Ivy Nicholson kissing Sam Green and Rufus Collins looking shocked, we get a serious of very happy and very loud commercials. Indeed, after watching the silent and grainy soap opera footage, it’s a bit jarring to have an expertly staged commercial suddenly blare forth in crisp black-and-white. An obnoxious salesman tries to sell us things to make our home better and our meals tastier. Jerry Lewis shows up with a child and tells us to be sure to contribute money to his telethon. Model Rosemary Kelly is introduced by an announcer who tells us that Rosemary is going to tell us about the greatest adventure of her life. That adventure? Not conditioning her hair for five days. Amazingly, her hair is still full and lustrous! Even after swimming and sleeping on it! Not even a broken steam valve can make her hair look bad! This commercial is so effective that it’s actually featured twice and why not? Even I want to know Rosemary’s secrets and my hair always looks good!

Warhol subtitled this film The Lester Persky Story, both to thank Persky for supplying the commercials but also to point out that the commercials were really the whole point of the show. The plot of any show, whether it’s a real one or the one in Warhol’s film, really only exists to keep you watching long enough to see the commercials. And it must be said that the commercials are the most interesting part of this film. After watching the Soap Opera actors for ten minutes, it’s a relief when Rosemary Kelly appears and, with a big smile on her face, starts enthusiastically talking about her hair. We all complain about commercials but we still accept them as a fact of life and, in the end, it’s usually the commercials that people remember and try to pattern their lives after. I mean, there’s a reason why I’m still singing that “Nothing is everything” song from the Skyrizi commercials.

And now, let’s check out how Rosemary Kelly’s hair is doing in hurricane winds!