“Friends forever. It’s a nice idea.”

With those words, the late Casey Kasem closed out the infamous “Rockumentary” episode of Saved By The Bell. In this episode, Zack Morris fell asleep in his garage while waiting for his high school friends to arrive for band rehearsal. While he was asleep, he dreamt about becoming a superstar as the result of Zack Attack’s hit song, Friends Forever. Later, of course, Zack was led astray by a publicist who tried to sell him as being a “male Madonna.” Zack didn’t care about the fame. He was more concerned that the music and the lights at his concert were so excessive that the audience couldn’t even hear his lyrics. Because, seriously, when you’re coming up with banger lyrics like “We’ll be friends forever/yes we will,” you want to make sure that they can clearly be heard.

It’s easy to make fun of the band and the show but that doesn’t make Casey Kasem’s words any less true. Friends forever. It is a nice idea. It’s also a totally unrealistic and implausible idea. People grow apart. People develop new interests. People move to different towns. Sometimes, people just decided that they need to take a little break from the same old thing. Instead of demanding that people remain friends forever, it would perhaps be more realistic to encourage people to enjoy and treasure the time that they have in the present. But, to be honest, entertainment is not about that type of reality. No one wants to hear, “Be friends until you get bored.” Instead, they want to hear “Friends forever!” It’s a simple idea and the simple ideas are the ones that usually bring us the most comfort.

Take the idea behind Shangri-La, for instance. Shangri-La was a utopia that was hidden away in the Himalayas. It was a place where there was no war, no greed, and everyone was in nearly perfect health. It was a place where it was common for people to live to be well over a hundred years old. It’s a place where people literally can be friends forever. And while the place does have one very big drawback — i.e., once you decide to stay there, you can’t return to the outside world for even so much as a brief visit — it’s still easy to see why this idealized existence would appeal to many people.

The lamasery of Shangri-La was first introduced in a 1933 novel called Lost Horizon. Written by James Hilton, Lost Horizon told the story of a group of westerners who, fleeing from a political uprising in India, find themselves in Shangri-La. That the novel’s portrayal of a peaceful utopia hidden away from the “modern world” proved to be popular should not come as a surprise. In 1933, the world was still recovering from the Great War. Much of Europe was still in ruins, both economically and physically. The combination of the First World War and the Spanish Flu pandemic had shaken everyone’s faith in the future. Even as a group of idealistic activists, industrialists, and politicians tried to make war illegal, Mussolini seized power in Italy. Spain was on the verge of civil war. In Germany, a fanatical anti-Semite named Adolf Hitler had managed to move from being a fringe politician to being named chancellor. The U.S. was suffering from the Great Depression. Even the UK was so mired in political turmoil that it was no longer a reliable bulwark against chaos. To the readers who were having to deal with all of that on a daily basis, the idea of Shangri-La was an inviting one.

(One of those readers was Franklin D. Roosevelt, who named his presidential retreat Shangri-La. Years later, Dwight Eisenhower would rename Shangri-La after his son and it’s remained Camp David ever since.)

Not surprisingly, the book’s success led to it being adapted for the movies. Frank Capra took the first crack at it, release his film version in 1937. At the time, Capra’s adaptation was the most expensive film to have ever come out of Hollywood. (It cost $1.6 million dollars!) It also underperformed at the box office, nearly bankrupting Colombia Pictures. Even though the film itself was nominated for Best Picture of the year, it still took five years for the film to earn back its cost. Because Colombia edited the film to shorten its lengthy running time, Capra sued the studio and the end result was that everyone involved lost a good deal of money. Considering all of the bad luck that befell the first production, one might wonder why Hollywood would even risk making a second version of the film. And indeed, it would be several decades before any major studio attempted to bring Hilton’s novel back to the screen, despite the fact that the idea behind Shangri-La was probably looking more attractive with each crisis-filled day.

Ross Hunter

In 1973, producer Ross Hunter was sleeping on a mountain of cash. Well, perhaps he wasn’t but a look at some of the films that he had produced would definitely suggest that he could have if he had so chosen. Hunter started his career producing melodramas that starred Rock Hudson and were often directed by Douglas Sirk. He was the type of producer who understood that importance of glitz and glamour, especially with the film industry facing a new competitor named television. In the 60s, he made films that were totally out-of-touch with the turmoil of the decade but which still appealed to middle-aged viewers who wanted an escape from the hippies and the assassins. In 1970, he scored his biggest hit of all time when he produced Airport. As dull as that film seems to us today, it was the biggest hit of 1970 and it also gave birth to the disaster genre. (It was also the only Ross Hunter production to be nominated for Best Picture.)

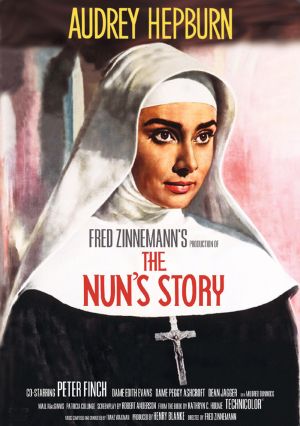

It was after the success of Airport that Ross Hunter decided to produce a remake of Lost Horizon. Following the approach that he used in Airport he gathered an all-star cast. In fact, George Kennedy appeared in both Airport and Lost Horizon! Joining Kennedy were Oscar nominees Sally Kellerman, John Gielgud, Charles Boyer, Peter Finch, and Liv Ullmann. Michael York, fresh off of Cabaret, and Olivia Hussey, who was best-known for playing Juliet in the wildly successful 1968 version of Romeo and Juliet, were cast as rebellious lovers who tried to escape the paradise of Shangri-La. Larry Kramer, the future playwright and political activist, was hired to write the script. Charles Jarrott, who specialized in big, glossy films and who had been nominated for Best Director for his work on Anne of a Thousand Days, was brought in to direct. And Burt Bacharach was enlisted to write the song because, on top of being a literary adaptation with an all-star cast, Lost Horizon was also going to be a musical.

What could go wrong?

What indeed.

The 1973 version of Lost Horizon opens with an endless aerial view of the Himalayas. In the background, singers sing about peace and love. “There’s a lost horizon/waiting to be found/where the sound of guns/don’t pound in your ears/anymore,” the singers repeat several times, as if to hammer home the fact that the audience is not about to get Burt Bacharach at his best.

When the opening credits finally end, we find ourselves at an airport. A very non-musical protest has broken out. The characters in the film describe it as a revolution but instead, it just looks like a bunch of confused extras standing on a landing strip. When it comes to an epic film like this, it’s always a good idea to see what the extras are doing. In a good film, the extras will actually be a part of the world onscreen and you won’t even think of them as being a crowd of paid performers. In a bad film, like this one, they’ll all stand around in a perfectly organized group and they’ll all do the exact the same thing at the same time, like shaking their fists at a plane.

Despite all of the “drama” at the airport, one airplane does manage to take off. On the plane are the Conways, diplomat Richard (Peter Finch) and his younger brother, George (Michael York, whose blond prettiness suggests that there’s not a chance he could share any DNA with the much more rough-hewn Peter Finch). There’s also a Newsweek photographer named Sally Hughes (Sally Kellerman), who pops pills and who suffers from a pronounced case of ennui. She describes her job as “taking pictures of the headless so that people with heads can look at them in magazines while getting their hair done.” (Damn, Newsweek apparently used to be really messed up publication!) Sam Cornelius (George Kennedy) is an engineer and an embezzler. And finally, there’s Harry Lovett (Bobby Van), who introduces himself to everyone as being “Harry Lovett, the comedian.” Harry was playing an USO show when the revolution broke out and apparently, he was abandoned in the country because his act was so bad. Is the film suggesting that, in 1973, the United States would actually abandon a citizen in a dangerous, war-torn country? I hope someone impeaches that President Nixon!

Our heroes may think that they’re escaping to freedom but it turns out that the plane is actually being hijacked! One thing leads to another and eventually, as happens in all good musicals, the plane cashes in a remote area of the Himalayas. At first, it seems like our heroes are done for but, fortunately, they’re discovered by Chang (the very British John Gielgud) and a group of Shangri-La monks. Chang leads the party through the snowy mountains and eventually, they arrive at what appears to be a Disney resort but what we’re told is actually Shangri-La, a tropical paradise that sits in the middle of one of the most dangerous places on Earth!

Shangri-La has something for everyone:

Sally gets off drugs and discovers a library that, oddly enough, has every book ever written even though no one knows where Shangri-La is, none of the inhabitants can leave the area without running the risk of rapidly again, and Amazon wasn’t a thing in 1973.

Sam discovers a gold mine but, realizing that money doesn’t matter, he instead uses his engineering skills to help out the farmers of Shangri-La. It really didn’t appear that the farmers of Shangri-La needed any help but whatever, I guess. As long as Sam is happy.

Harry Lovett becomes a big star as the children of Shangri-La love his comedy. Children are well-known for their lack of taste when it comes to comedy.

Richard not only falls in love with the local teacher (Ingmar Bergman’s muse, Liv Ullman) but he also meets the High Lama (the very French Charles Boyer). It turns out that the High Lama is finally going to die and that he’s determined that Richard is the man who is destined to take over Shangri-Law, despite the fact that Richard has only recently arrived and isn’t even a Buddhist.

In fact, almost everyone is so happy that they start to sing and dance! It takes 50 minutes for the film to reach its first big musical number. Unfortunately, there’s a reason why most successful film musicals open with a big number instead of holding off on it. It’s important to, early on, get the audience used to the idea that they’re watching a film set in a world where it’s perfectly common for people to break out into song. From West Side Story to La La Land, good musicals have understood the importance of bringing the audience in early. Lost Horizon waits until everyone has gotten used to the film being a somewhat rudimentary adventure/disaster film before suddenly springing the singing and the dancing on everyone. It’s a bit jarring. It wouldn’t matter, of course, if the songs were any good but again, this was not Burt Bacharach’s finest moment.

Unfortunately, one member of the group doesn’t want to stay in Shangri-La and dance and sing. George Conway does not want to be friends forever. Instead, he’s fallen in love with the local librarian, Maria (Olivia Hussey). Maria dreams of seeing New York and London. George is determined to grant her wish, despite being told that Maria is nearly as old as John Gielgud and will start to age as soon as she leaves Shangri-La. Richard feels an obligation to accompany his brother. Needless to say, things don’t go well. (As Michael York would later put it himself, “There is noooo sanctuary….”) Will Richard be able to find his way back to Shangri-La?

“Let’s not go to Camelot, ’tis a silly place,” King Arthur famously declared in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Lost Horizon suffers the opposite problem. While Lost Horizon’s Shangri-La is occasionally a silly place, it’s usually just an incredibly boring place. One can’t help but feel that Maria has a point, regardless how much time Sally spends singing about her hatred of the New York night life. The film’s downfall is that it argues for Shangri-La being viewed an ideal without making Shangri-La into any place that you would want to visit. Add in the anemic songs and the confused performances and Charles Jarrot’s inability to maintain any sort of compelling pace and you have a film that’s too dull to really even qualify as a fun bad film. It’s just bad.

That said, much like friends forever, Shangri-La is a nice idea.

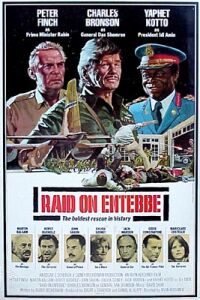

On June 27th, 1976, four terrorists hijacked an Air France flight and diverted it to Entebbe Airport in Uganda. With the blessing of dictator Idi Amin and with the help of a deployment of Ugandan soldiers, the terrorists held all of the Israeli passengers hostage while allowing the non-Jewish passengers to leave. The terrorists issued the usual set of demands. The Israelis responded with Operation Thunderbolt, a daring July 4th raid on the airport that led to death of all the terrorists and the rescue of the hostages. Three hostages were killed in the firefight and a fourth — Dora Bloch — was subsequently murdered in a Ugandan hospital by Idi Amin’s secret police. Only one commando — Yonatan Netanyahu — was lost during the raid. His younger brother, Benjamin, would later become Prime Minister of Israel.

On June 27th, 1976, four terrorists hijacked an Air France flight and diverted it to Entebbe Airport in Uganda. With the blessing of dictator Idi Amin and with the help of a deployment of Ugandan soldiers, the terrorists held all of the Israeli passengers hostage while allowing the non-Jewish passengers to leave. The terrorists issued the usual set of demands. The Israelis responded with Operation Thunderbolt, a daring July 4th raid on the airport that led to death of all the terrorists and the rescue of the hostages. Three hostages were killed in the firefight and a fourth — Dora Bloch — was subsequently murdered in a Ugandan hospital by Idi Amin’s secret police. Only one commando — Yonatan Netanyahu — was lost during the raid. His younger brother, Benjamin, would later become Prime Minister of Israel.