Seven minutes into the 1935 film, The Murder Man, 27 year-old James Stewart makes his film debut.

He’s playing a reporter named Shorty and, since this is a 30s newspaper film, he’s first seen sitting at a table with a bunch of other cynical reporters, the majority of whom seem to be alcoholics and gambling addicts. Suddenly, words comes down that a corrupt businessman named Halford has been assassinated, shot by an apparent sniper. (It is theorized that he was shot from one of those carnival shooting gallery games, which was somewhat oddly set up on a street corner. Maybe there was shooting galleries all over place in 1935. I supposed people had to do something to keep their spirits up during the Depression.) While the other reporters run to the scene of the crime, Shorty is on the phone and calling his editors to let them know that a huge story is about to break.

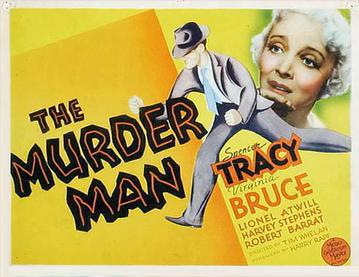

Steve Grey (Spencer Tracy) is the reporter assigned to the story. Crime is his beat and everyone agrees that no one’s better at covering criminals and understanding what makes them tick. Unfortunately, it’s not always easy to track Steve down. He’s a hard drinking reporter and lately, he’s been concerned about the collapse of his father’s business. Still, when Steve is finally tracked down, he throws himself into covering the story and speculating, in print, about who could have killed Halford. In fact, his girlfriend (Virginia Bruce) worries that Steve is working too hard and that he’s developing a drinking problem. She suggests that Steve needs to take some time off but Steve is driven to keep working.

It’s largely as a result of Steve’s actions that a man named Henry Mander (Harvey Stephens) is arrested and convicted of Halford’s murder. Steve should be happy but instead, he seems disturbed by the fact that he is responsible for Mander going to jail. When his editor requests that Steve go to Sing Sing to interview Mander, a shocking truth is revealed.

Admittedly, the main reason that I watched The Murder Man was because it was the feature film debut of James Stewart. (Stewart previously appeared in a comedy short that starred Shemp Howard.) Stewart is only in a handful of scenes and he really doesn’t have much to do with the main plot. To be honest, Shorty’s lines could have been given to anyone. That said, Stewart still comes across as being a natural on camera. As soon as you hear that familiar voice, you can’t help but smile.

Even if Stewart hadn’t been in the film, I would have enjoyed The Murder Man. It’s fast-paced mystery and it has a decent (if not totally unexpected) twist ending. It’s one of those films from the 30s where everyone speaks quickly and in clipped tones. Casual cynicism is the theme for the day. Spencer Tracy gives a wonderful performance as the hard-drinking and troubled Steve Grey and the scene where he meets Mander in prison is surprisingly moving. Clocking in at only 68 minutes, The Murder Man is a good example of 30s Hollywood.