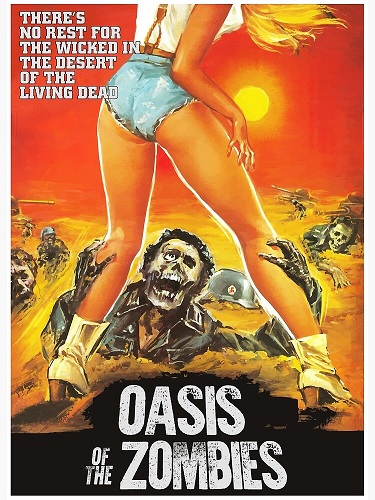

1982’s Oasis of the Zombies opens with two girls in a jeep who just happen to be driving through the middle of a desert in Africa. When they come across an oasis, they decided to stop so that they can walk around and allow the camera to focus on their rear ends as they explore the area while wearing short shorts. Unfortunately, it turns out that they’re not very good when it comes observing details because they totally miss the skulls and the pieces of metal that have been decorated with swastikas. One girl thinks that the oasis is creepy. The other wants to keep exploring. Decayed hands suddenly rise out of the ground and attack both of them.

(Oddly enough, the girls reminded me of myself and my BFF, Evelyn. I called Evelyn after I watched the movie and we both agreed that getting attacked by desert zombies is definitely something that will probably happen to us in the near future.)

After the two girls are zombied, the film cuts to an old man named Captain Blabert (Javier Maiza) telling another man named Kurt Meitzell (either Henri Lambert or Eduardo Fajardo, depending on which version of the film you see) about a shipment of Nazi gold that, for the past few decades, has been sitting in the middle of an oasis in the desert. Kurt kills Blabert and then heads off with his wife (Myriam Landson or Lina Romay, again depending on which version of the film you see) to track down the gold.

We then cut to London, where college student Robert Blabert (Manuel Gelin) receives not only a message informing him of the death of his father, Captain Blabert, but also a journal that leads to several flashbacks of Captain Blabert serving in Africa during World War II and getting involved with the Nazis and a sheik.

Eventually, Robert and several of his friends end up going to Morocco, where they randomly meet two filmmakers and everyone decides to head into the desert to search for the oasis and the gold. Fortunately, the oasis and the gold are both easy to find. However, the oasis is still defended by the Nazis who were assigned to transport the gold. Of course, the Nazis are all zombies now!

Oasis of the Zombies is a Jesus Franco film and, like many of his later films, it’s more than a little disjointed. The film’s scenes don’t always seem to follow any sort of conventional narrative logic. Instead, the scenes often feel as if they’ve been randomly assembled and the end result is a low-budget zombie film that plays out like a fragmented dream, one that seems to feature more stock footage than actual plot. Franco himself frequently seems as if he’s having trouble concentrating on just what exactly Oasis of the Zombies is supposed to be about. Random zoom shots are mixed in with shots of a spider building its web and, more than once, the action comes to a stop so the film can turn into an extended travelogue. As was so often the case with Franco’s later films, some of the shots are striking. There’s a shot of a man standing on a roof announcing the call to prayer that achieves a surreal grandeur and, as bad as the zombie makeup is, the shots of the living dead silhouetted in the desert are effective. But for every effective shot, there’s shots of people looking straight at the camera. Franco was director who could both frame a memorable shot and also be remarkably sloppy. As such, his aesthetic transcends conventional definitions of good and bad. Viewers either get him and his semi-improvised excursions into existential horror or they don’t.

Myself, I thought there were enough good shots in Oasis of the Zombies to make it worth watching. Certainly, it’s not comparable to Franco’s better films, like The Awful Dr. Orlof or Faceless. But it’s also not quite as bad as its online reputation might suggest. The zombies relentlessly emerging in the desert are creepy and, in its better moments, the film does capture the feeling of being stranded in the middle of nowhere. One could argue that the film actually does have a deeper meaning, with the Nazi zombies representing the fact that, for all of its defeats, the hate that fueled the Nazis is still alive and still dangerous. In the end, it’s a zombie flick, featuring less than impressive zombie makeup and some adequate gore and it’s undoubtedly a Jess Franco film. There’s no mistaking Franco’s vision for anyone else’s.

Finally, there are two versions of the film. The French-language version features Henri Lambert and Myriam Landson as Kurt and his wife. The Spanish-language version features Franco regulars Eduardo Fajardo and Lina Romay as the couple. Other than the scenes with Kurt, the two versions of Oasis of the Zombies are pretty much the same. As far as I know, the French-language version is the only one that is available in the States. That’s the one that I watched for this review.