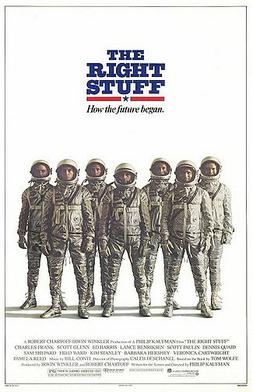

There’s a brilliant scene that occurs towards the end of 1983’s The Right Stuff.

It takes place in 1963. The original Mercury astronauts, who have become a symbol of American ingenuity and optimism, are being cheered at a rally in Houston. Vice President Lyndon Johnson (Donald Moffat) stands on a stage and brags about having brought the astronauts to his supporters. One-by-one, the astronauts and their wives wave to the cheering crowd. They’re all there: John Glenn (Ed Harris), Gus Grissom (Fred Ward), Alan Shephard (Scott Glenn), Wally Schirra (Lance Henrisken), Deke Slayton (Scott Paulin), Scott Carpenter (Charles Frank), and the always-smiling Gordon Cooper (Dennis Quaid). The astronauts all look good and they know how to play to the crowd. They were chosen to be and sold as heroes and all of them have delivered.

While the astronauts are celebrated, Chuck Yeager (Sam Shepard) is at Edwards Air Force Base. Yeager is the pilot who broke the sound barrier and proved that the mythical “demon in the sky,” which was whispered about by pilots as a warning about taking unnecessary risks, was not waiting to destroy every pilot who tried to go too fast or too high. Yeager is considered by many, including Gordon Cooper, to be the best pilot in America. But, because Yeager didn’t have the right image and he had an independent streak, he was not ever considered to become a part of America’s young space program. Yeager, who usually holds his emotions in check, gets in a jet and flies it straight up into the sky, taking the jet to the edge of space. For a few briefs seconds, the blue sky becomes transparent and we can see the stars and the darkness behind the Earth’s atmosphere. At that very moment, Yeager is at the barrier between reality and imagination, the past and the future, the planet and the universe. And watching the film, the viewer is tempted to think that Yeager might actually make it into space finally. It doesn’t happen, of course. Yeager pushes the jet too far. He manages to eject before his plane crashes. He walks away from the cash with the stubborn strut of a western hero. His expression remains stoic but we know he’s proven something to himself. At that moment, the Mercury Astronauts might be the face of America but Yeager is the soul. Both the astronauts and Yeager play an important role in taking America into space. While the astronauts have learned how to take care of each other, even the face of government bureaucracy and a media that, initially, was eager to mock them and the idea of a man ever escaping the Earth’s atmosphere, Chuck Yeager reminds us that America’s greatest strength has always been its independence.

Philip Kaufman’s film about the early days of the space program is full of moments like that. The Right Stuff is a big film. It’s a long film. It’s a chaotic film, one that frequently switches tone from being a modern western to a media satire to reverent recreation of history. Moments of high drama are mixed with often broad humor. Much like Tom Wolfe’s book, on which Kaufman’s film is based, the sprawling story is often critical of the government and the press but it celebrates the people who set speed records and who first went into space. The film opens with Yeager, proving that a man can break the sound barrier. It goes on to the early days of NASA, ending with the final member of the Mercury Seven going into space. In between, the film offers a portrait of America on the verge of the space age. We watch as John Glenn goes from being a clean-cut and eager to please to standing up to both the press and LBJ. Even later, Glenn sees fireflies in space while an aborigines in Australia performs a ceremony for his safety. We watch as Gus Grissom barely survives a serious accident and is only rescued from drowning after this capsule has been secured. The astronauts go from being ridiculed to celebrated and eventually respected, even by Chuck Yeager.

It’s a big film with a huge cast. Along with Sam Shepherd and the actors who play the Mercury Seven, Barbara Hershey, Pamela Reed, Jeff Goldblum, Harry Shearer, Royal Dano, Kim Stanley, Scott Wilson, and William Russ show up in roles both small and large. It can sometimes be a bit of an overwhelming film but it’s one that leaves you feeling proud of the pioneering pilots and the brave astronauts and it leaves you thinking about the wonder of the universe that surrounds our Earth. It’s a strong tribute to the American spirit, the so-called right stuff of the title.

The Right Stuff was nominated for Best Picture but, in the end, it lost to a far more lowkey film, 1983’s Terms of Endearment. Sam Shepard was nominated for Best Supporting Actor but lost to Jack Nicholson. Nicolson played an astronaut.