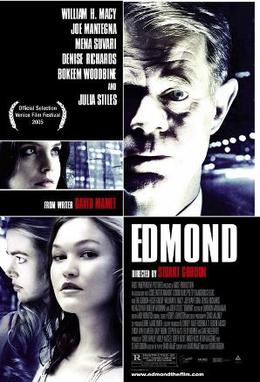

Based on a one-act play by David Mamet, 2005’s Edmond tells the story of Edmond Burke (William H. Macy).

Edmond shares his name (if not the actual spelling) with the philosopher Edmund Burke. Edmund Burke was a strong believer that society had to put value in good manners to survive and that religious and moral institutions played an important role in promoting the idea of people treating each other with respect and decency. Edmund Burke knew what he believes and his writings continue to influence thinks to this day. Edmond Burke, on the other hand, doesn’t know what he believes. He doesn’t know who he wants to be. All he knows is that he doesn’t feel like he’s accomplished anything with his life. “I don’t feel like a man,” he says at one point to a racist bar patron (played by Joe Mantegna) who replies that Edmond needs to get laid.

On a whim, Edmond steps into the shop of a fortune teller (Frances Bay), who flips a few Tarot cards and then tells Edmond that “You’re not where you’re supposed to be.” Edmond takes her words to heart. He starts the night by telling his wife (played by Mamet’s wife, Rebecca Pidgeon) that he’s leaving their apartment and he won’t be coming back. He goes to the bar, where he discusses his marriage with Mantegna. He goes to a strip club where he’s kicked out after he refuses to pay $100 for a drink. He goes to a peep show where he’s frustrated by the glass between him and the stripper and the stripper’s constant demand that he expose himself. He gets beaten in an alley by three men who were running a three-card monte scam. Edmond’s problem is that he left home without much cash and each encounter leads to him having less and less money. If he can’t pay, no one wants to help him, regardless of how much Edmond argues for a little kindness. He pawns his wedding ring for $120 but apparently, he just turns around and uses that money to buy a knife. An alley-way fight with a pimp leads to Edmond committing his first murder. A one-night stand with a waitress (a heart-breaking Julia Stiles) leads to a second murder after a conversation about whether or not the waitress is actually an actress leads to a sudden burst of violence. Edmond ends up eventually in prison, getting raped by his cellmate (Bookem Woodbine) and being told, “It happens.” Unable to accept that his actions have, in one night, led him from being a businessman to a prisoner, Edmond says, “I’m ready to go home now.” By the end of the film, Edmond realizes that perhaps he is now where he was meant to be.

It’s a disturbing film, all the more so because Edmond is played by the likable William H. Macy and watching Macy go from being a somewhat frustrated but mild-mannered businessman to becoming a blood-drenched, racial slur-shouting murderer is not a pleasant experience. Both the play and the film have generated a lot of controversy due to just how far Edmond goes. I don’t see either production as being an endorsement of Edmond or his actions. Instead, I see Edmond as a portrait of someone who, after a lifetime of being willfully blind to the world around him, ends up embracing all of the ugliness that he suddenly discovers around him. He’s driven mad by discovering, over the course of one night, that the world that is not as kind and well-mannered as he assumed that it was and it all hits him so suddenly that he can’t handle it. He discovers that he’s not special and that the world is largely indifferent to his feelings. He gets overwhelmed and, until he gets his hands on that knife, he feels powerless and emasculated. (The knife is an obvious phallic symbol.) It’s not until the film’s final scene that Edmond truly understands what he’s done and who he has become.

Edmond is not always an easy film to watch. The second murder scene is truly nightmarish, all the more so because the camera remains on Edmond as he’s drenched in blood. This is one of William H. Macy’s best performances and also one of his most disturbing characters. That said, it’s a play and a film that continues to be relevant today. There’s undoubtedly a lot of Edmonds out there.

To quote “Dirty” Harry Callahan, “I’m all broken up about his rights.”

To quote “Dirty” Harry Callahan, “I’m all broken up about his rights.”