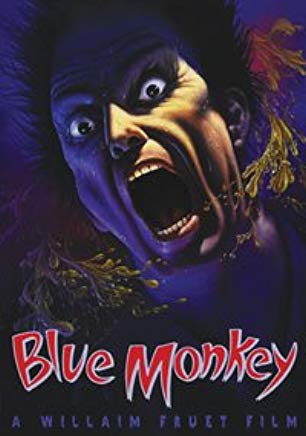

Last night, as I sat down to watch the 1987 Canadian film, Blue Monkey, I found myself singing a song in my head:

How does it feel

When you treat me like you do

And you’ve laid your hands upon me

And told me who you are?

I thought I was mistaken

And I thought I heard your words

Tell me, how do I feel?

Tell me now, how do I feel?

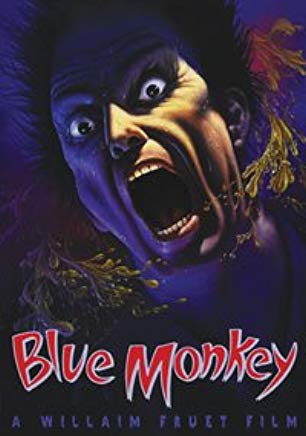

Unfortunately, it turned out that the only thing Blue Monkey had in common with the classic New Order song, Blue Monday, was an enigmatic title. Just as the song never really mentions anything about Monday, Blue Monkey does not feature a single monkey. One minor character does mention having a dream about a monkey but, otherwise, there are no monkeys in the film. Speaking as someone who believes that almost any film can be improved the presence of a monkey, I was disappointed.

(Seriously, Nomadland would have been a hundred times better if Frances McDormand had a pet monkey.)

What Blue Monkey does have is a lot of blue. The characters wear blue shirts and some wear blue uniforms. Another wears a blue hat. The film takes place in a hospital where almost all of the walls are painted blue. Even worse, the majority of the film’s scenes are saturated with blue lighting.

Here’s just two screenshots:

Seriously, some scenes were so blue that I was reminded of John Huston’s decision to suffuse Reflections in a Golden Eye with the color gold. Personally, I think Huston made a mistake when he did that with Reflections but I can still understand the reasoning behind the decision and I can see what Huston was attempting to accomplish. The blue in Blue Monkey feels like a distraction, as if someone realized, on the day before shooting, that the title didn’t make any damn sense. “We’ll just make the whole movie blue!”

The problem, of course, is that the film goes so overboard with the blue lighting that it actually becomes difficult to look at the screen for more than a few minutes. I had to keep looking away, specifically because all of those blue flashing lights were starting to make me nauseous and were on the verge of giving me a migraine. At times, the image is so saturated in blue that you literally can’t make out what’s happening in the scene. Of course, once you do figure out what’s happening, you realize that it doesn’t matter.

Blue Monkey takes place in a hospital. A handyman has been having convulsions after pricking his finger on a plant that came from a mysterious island. Perhaps that’s because a mutant larvae is now using his body for a host. The larvae eventually develops into a giant grasshopper — NOT A MONKEY! — who stalks around the hospital and kills a few people. The Canadian government is threatening to blow up the hospital unless something is done about the blue grasshopper.

It’s a Canadian exploitation film but Michael Ironside isn’t in it so it somehow feels incomplete. That said, John Vernon plays a greedy hospital administrator and it’s fun to watch him get irritated with everyone. A very young Sarah Polley has an early role as an annoying child. There’s actually several children in this film and you’ll want to throw something at the screen whenever they show up, that’s just the type of film this is. (Some of my fellow movie-watching friends were actually upset that the children survived that film. I wouldn’t go that far but I still found myself hoping John Vernon would tell them all to shut up and let the adults handle things.) Susan Anspach plays a doctor, showing that anyone can go from Five Easy Pieces to Canadian exploitation. The film’s nominal star is Steve Railsback, playing a cop who comes to the hospital to check on his wounded partner and who ends up on grasshopper duty. Steve Railsback has apparently said that he’s embarrassed to have appeared in this film. Consider some of the other films that Steve Railsback has appeared in and then reread that sentence.

In the end, Blue Monkey doesn’t add up too much. There’s no Michael Ironside. There’s no monkeys. There’s just a lot of blue.