1963’s The Sadist opens with three teachers driving to a baseball game.

Ed (Richard Alden), Doris (Helen Hovey), and Carl (Don Russell) are planning on just having a nice night out but their plans change when they have car trouble out in the middle of nowhere. They pull into a gas station/junkyard that happens to be sitting off the side of the road. The teachers look for the owner of the gas station or at least someone who works there. Instead, what they find is Charlie Tibbs (Arch Hall, Jr,) and bis girlfriend, Judy Bradshaw (Marilyn Manning).

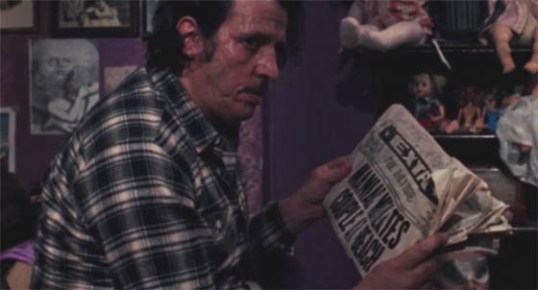

Charlie is carrying a gun and he demands that the teachers repair their car and then give it to him so that he and Judy can continue their journey across the country. Charlie has been switching cars frequently, largely because the cops are looking for him. That’s because Charlie has been killing people all up and down the highway. The intellectual teachers find themselves being held hostage by Charlie and Judy, two teenagers who may not be as smart as them but who have the killer instinct that the teachers lack.

It’s interesting to watch The Sadist after watching Eegah! Arch Hall, Jr. and Marilyn Manning played boyfriend and girlfriend in that one as well but neither Hall nor Manning were particularly credible in their roles. Hall seems uncomfortable with the whole teen idol angle of his role while Manning seemed a bit too mature for the role of a teenager. In The Sadist, however, they’re both not only believable but they’re terrifying as well.

Charlie and Judy are almost feral in their ferocity, with both taking a disturbing glee in taunting the teachers. Charlie kills without blinking and Judy enjoys every minute of it. It’s easy to imagine Charlie and Judy at a drive-in showing of Eegah!, laughing at the sight of the caveman getting gunned down by the police and never considering that violence in real life is different from killing in the movies. The teachers discover that it’s impossible to negotiate with Charlie and that Charlie’s promise not to try to kill them if they fix the car is ultimately an empty one. And yet the teachers, dedicated to education and trying to reach even the most difficult of students, struggle to fight back. They’re held back by their conscience, something that Charlie does not possess. It’s intelligence vs instinct and this film suggests that often, intelligence does not win.

It’s a pretty intense and dark film, one that makes great use of that junkyard setting and which is notable for being the first film to feature the cinematography of Vilmos Zsigmond. For those who appreciate B-movies, it’s memorable for showing that, when he wasn’t being pushed to be a squeaky-clean hero who sang sappy ballads in films directed by his father, Arch Hall, Jr. actually was capable of giving a very good performance.

The Sadist was based on the true-life crimes of Charlie Starkweather and Caryl Ann Fugate. Interestingly enough, their crimes also inspired Terence Malick’s Badlands.