For my next back to school film, I watched the 1965 underground film, Vinyl!

Now, admittedly, Vinyl does not appear to take place in a high school. Then again, maybe it does. All of the action takes place in a cramped corner of a room and we’re never really told, for sure, where the room is located. All we know is that various characters keep wandering in and out of the static frame while the film’s action unfolds.

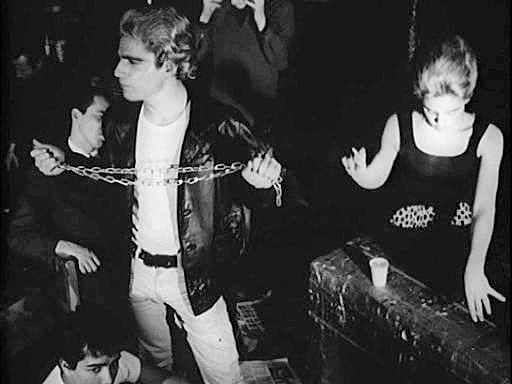

The center of the film is Victor (Gerald Malanga) who appears to be in his late 20s but who insists to us that he’s a “J.D,” which stands for juvenile delinquent. He does what he wants, whether that means lifting weights or enthusiastically dancing. Victor may be a murderous teenager with a bad attitude but he truly loves rock music.

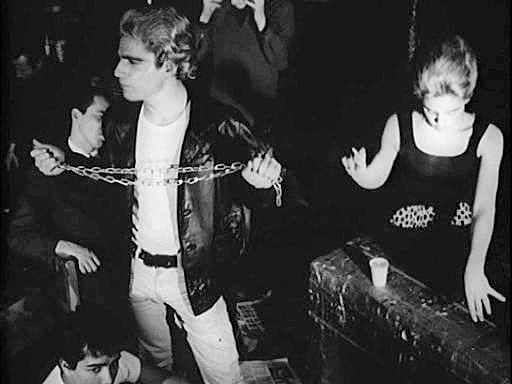

While Victor dances and occasionally stumbles his way through a monologue about being a J.D, there’s an ever-present audience in the background of the scene. Occasionally, they seem to be interested in what Victor is saying but, just as often, they seem to be bored with the whole thing. Sitting off to Victor’s right and smoking through nearly the entire film is the iconic and tragic Edie Sedgwick. Occasionally, she dances but, for the most part, she’s just observes with an enigmatic half-smile on her face.

Eventually, some men who we assume are the police get tired of Victor dancing and boasting about being a delinquent so they grab him, tie him to a chair, and force him to wear bondage gear while they beat him. It’s a new, government-sanctioned rehabilitation technique and it’s guaranteed to turn Victor is a responsible member of society. While they torture him, they play vinyl records in the background and Victor, possibly to his horror though, due to Malanga’s out-of-it performance, it’s often difficult to surmise what’s going on in Victor’s head, realizes that his beloved rock music is now being used to torture him.

All the while, Edie watches from the corner of the screen. She smokes a cigarette. She dances. Sometimes, someone will refill her drink. She holds a candle for a while. As a viewer who is more than a little obsessed with the tragically short life of Edie Sedgwick and who relates to her on a personal level, it was occasionally difficult for me to watch because, even in a non-speaking role, Edie’s star power was obvious.

Edie!

Of course, Edie isn’t the only person watching as Victor is tortured. Many people wander in and out of the frame. (Vinyl lasts 70 minutes and features exactly three shots.) For the most part, the majority of them regard the torture happening in from with a studied detachment. In fact, they’re very detachment and they’re very refusal to act in any sort of expected way becomes rather fascinating. Vinyl goes so far out of it’s way to defy our expectations of what a movie should be that it becomes one of the most watchable unwatchable movies ever made.

Vinyl was directed by Andy Warhol. Reportedly, it was filmed without any rehearsal and without multiple takes. Hence, when Malanga stumbles over his lines or occasionally turns his back to camera, the moment is preserved. When Edie Sedgwick breaks character and laughs, the film keeps on rolling. When another actor accidentally drops his papers and has to spend half a minute picking them up and trying to get them back in order, it’s saved on camera. And, because it’s in the final cut, Gerald Malanga forgetting his lines becomes as much a cinematic moment as Humphrey Bogart telling Ingrid Bergman to get on that plane or Clark Gable saying that he didn’t give a damn. There is no editing and, as a result, there is no protection. Instead, we just get a group of eccentric outsiders in their amateur glory. Yes, it’s self-indulgent and deliberately alienating but it’s also undeniably fascinating. (It helps that, while he may not have been a good actor, Gerald Malanga had an absolutely fascinating face.) When one watches one of Warhol’s underground films, the question always arises as to whether he was a genius or a con artist. Vinyl would seem to suggest that he was both.

(“What’s the point of all this?” some viewers may ask. The point is that it was filmed and now you’re watching and, because he’s at the center of a static frame, Gerald Malanga is now a movie star.)

Though you might have a hard time realizing it from just watching the film, Vinyl was also the first cinematic adaptation of Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange. Victor was a stand-in for Alex and Alex’s love of Beethoven is replaced by Victor’s love for Motown. Six years later, Stanley Kubrick would release his better known adaptation of Burgess’s novel but Andy Warhol, Gerald Malange, and Edie Sedgwick all got there first.