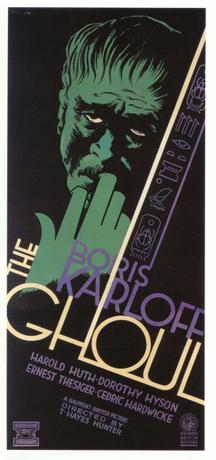

Some actors can make just about anything worth watching. That’s certainly the case with Boris Karloff and 1933’s The Ghoul.

In The Ghoul, Karloff plays Prof. Henry Moriant. The professor is an Egyptologist, a world-renowned expert on the dead. Moriant is now facing death himself, sick in bed and ranting about how he wants to be treated after he passes. Nigel Hartley (Ralph Richardson) stops by the mansion while pretending to be a vicar and offers to comfort Prof. Moriant in his last moments. The butler, Laing (Ernest Thesiger), explains that Moriant has never had much use for traditional religion. Instead, Moriant believes in the Gods of Egypt.

In death, Moriant wants to be buried with an Egyptian jewel in his hands. He believes that, after he dies, he will exchange the jewel with the Egyptian God Anubis and he will be reborn with amazing powers. However, when Moriant passes, Laing keeps the jewel for himself and attempts to hide it from the countess number of people who show up at the mansion, all seeking either the jewel or just information about Moriant’s estate. Moriant may not have been loved in life but everyone clearly loves his money.

Boris Karloff is not actually in that much of The Ghoul. He dominates the start of the film, ranting from his deathbed. And then, towards the end of the film, he rises from the dead and attacks those who he thinks have betrayed him and stolen the jewel. He’s only onscreen for a few minutes but he dominates those minutes. Karloff’s screen presence is undeniable. When he’s in a scene, he’s the only person that you watch. When he’s not in a scene, you find yourself wondering how long it’s going to take for Karloff to return.

That’s not to say that the other actors in The Ghoul aren’t good. The cast is full of distinguished names. Along with Richardson and Thesiger, Cedric Hardwicke, Anthony Bushnell, Dorothy Hyson, and Kathleen Harrison all wander through the mansion and try to avoid getting caught up in Karloff’s vengeance. Harrison provides the film’s comic relief and I actually enjoyed her flighty performance. The film itself is so darkly lit and full of so many greedy characters that it was nice to have someone on a totally different wavelength thrown into the mix. That said, the majority of the actors are stuck with paper-thin characters and aren’t really allowed the time to make much of an impression. This is Karloff’s film, from the beginning to end. And while the film itself is definitely a bit creaky, Karloff is always enjoyable to watch.

The Ghoul was made at a time when Karloff, having become a star with Frankenstein, was frustrated with the roles that he was being offered in America. He returned to his native UK and promptly discovered that he was just as typecast over there as he was in the United States. For a long time, The Ghoul was believed to be a lost film. However, in 1968, a copy was discovered in Egypt of all places. It’s unfortunate that the film itself isn’t better but there’s no denying the power of Karloff the performer.