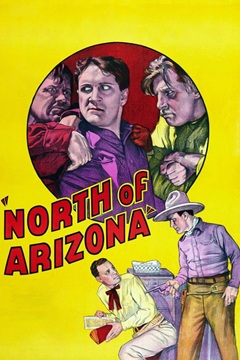

Newly hired ranch foreman Jack Loomis (Jack Perrin) comes to the aid of two Indians who were nearly swindled out of their land during a card game. The Indians inform Jack that his new boss, George Tully (Al Bridge), is actually a crook and the ranch is just a front for his criminal activities. When Jack says he doesn’t want to be a part of Tully’s schemes, Tully and his men frame Jack for a robbery.

Newly hired ranch foreman Jack Loomis (Jack Perrin) comes to the aid of two Indians who were nearly swindled out of their land during a card game. The Indians inform Jack that his new boss, George Tully (Al Bridge), is actually a crook and the ranch is just a front for his criminal activities. When Jack says he doesn’t want to be a part of Tully’s schemes, Tully and his men frame Jack for a robbery.

After you watch enough of these Poverty Row westerns, you start to get the feeling that anyone in the 30s could walk into a studio and star in a B-western. Jack Perrin was a World War I veteran who had the right look to be the star of several silent films but once the sound era came along, his deficiencies as an actor became very apparent. He could ride a horse and throw a punch without looking too foolish but his flat line delivery made him one of the least interesting of the B-western stars. That’s the case here, where Perrin is a boring hero and the entire plot hinges on the villain making one really big and really stupid mistake. John Wayne could have pulled this movie off but Jack Perrin was lost.

Jack Perrin’s career as a star ended just a few years after this film but not because he was a bad actor. Instead, Perrin filed a lawsuit after a studio failed to pay him for starring in one of their films. From 1937 until he retirement in 1960, Perrin was reduced to playing minor roles for which he often went uncredited. Hollywood could handle a bad actor but not an actor who expected to be paid for his work.