Today, the Shattered Lens wishes a happy birthday to actress Faye Dunaway.

In this scene from 1976’s Network, television executives Faye Dunaway and Robert Duvall discuss the best way to deal with Howard Beale and his falling ratings.

Today, the Shattered Lens wishes a happy birthday to actress Faye Dunaway.

In this scene from 1976’s Network, television executives Faye Dunaway and Robert Duvall discuss the best way to deal with Howard Beale and his falling ratings.

In this scene, from Arthur Penn’s 1967 film Bonnie and Clyde, Bonnie Parker (played by Faye Dunaway) writes a poem and tries to craft the future image of Bonnie and Clyde. Though it has none of the violence that made Bonnie and Clyde such a controversial film in 1967, this is still an important scene. (Actually, it’s more than one scene.) Indeed, this scene is a turning point for the entire film, the moment that Bonnie and Clyde goes from being an occasionally comedic attack on the establishment to a fatalistic crime noir. This is where Bonnie shows that, unlike Clyde, she knows that death is inescapable but she also knows that she and Clyde are destined to be legends.

(Of course, Dunaway and Warren Beatty — two performers who once epitomized an era but who are only seen occasionally nowadays — are already legends.)

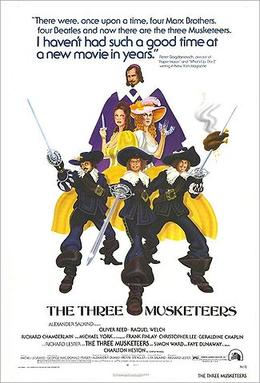

In 1973, director Richard Lester and producer Ilya Salkind decided to try to get two for the price of one.

In 1973, director Richard Lester and producer Ilya Salkind decided to try to get two for the price of one.

Working with a script written by novelist George McDonald Fraser, Lester and Salkind had assembled a once-in-a-lifetime cast to star in an epic film adaptation of Alexandre Dumas’s The Three Musketeers. Michael York was cast as d’Artagnan, the youthful swordman who goes from being a country bumpkin to becoming a King’s Musketeer. His fellow musketeers were played by Oliver Reed, Richard Chamberlain, and Frank Finlay. Faye Dunaway and Christopher Lee were cast as the villains, Milady and Rochefort. Charlton Heston played the oily Cardinal Richelieu. Geraldine Chaplin played Queen Anne while Simon Ward played the Duke of Buckingham. Comedic relief was supplied by Roy Kinnear as d’Artagnan’s manservant and Raquel Welch as Constance, d’Artagnan’s klutzy love interest. The film was a expensive, lushly designed epic that mixed Lester’s love of physical comedy with the international intrigue and the adventure of Dumas’s source material.

The only problem is that the completed film was too long. At least, that’s what Salkind and Lester claimed when they announced that they would be splitting their epic into two films. The cast and the crew, who had only been paid for one film, were outraged and the subsequent lawsuits led to the SAG ruling that all future actors’ contracts would include what was known as the Salkind clause, which stipulates that a a single production cannot be split into two or more films without prior contractual agreement.

But what about the films themselves? Both The Three Musketeers and The Four Musketeers are currently available on Tubi. I watched them over the weekend and, of the many films that have been made out of Dumas’s Musketeer stories, Richard Lester’s films are the best. Lester captures the swashbuckling spirit of the books while also turning them into two films that are easily identifiable as Lester’s work. There’s a lot physical humor to be found in Lester’s adaptation, especially during the first installment. d’Artagnan runs through the streets of Paris, convinced that he has been insulted by the haughty Rochefort. d’Artagnan manages to get challenged to three separate duels, all to take place on the same day. After his first swordfight as a member of the Musketeers, d’Artagnan tries to tell the men that he wounded about an ointment that will help them with their pain. Raquel Welch also shows a genuine flair for comedy as Constance, which makes her fate in the second film all the more tragic.

For all the controversy that it caused, splitting the story into two films was actually the right decision. If The Three Musketeers is an enjoyable adventure film, The Four Musketeers is far more serious. In The Four Musketeers, Oliver Reed’s melancholic Athos steps into the spotlight and his story of his previous marriage to the villainous Milady casts his character in an entirely new light. In The Four Musketeers, the combat is much more brutal and the humor considerably darker. Likable characters die. The Musketeers themselves commit an act of extrajudicial brutality that, while true to Dumas’s novel, would probably be altered if the film were made today. From being a naive bumpkin in The Three Musketeers, The Four Musketeers finds d’Artgnan transformed into a battle weary soldier.

For all the controversy that it caused, splitting the story into two films was actually the right decision. If The Three Musketeers is an enjoyable adventure film, The Four Musketeers is far more serious. In The Four Musketeers, Oliver Reed’s melancholic Athos steps into the spotlight and his story of his previous marriage to the villainous Milady casts his character in an entirely new light. In The Four Musketeers, the combat is much more brutal and the humor considerably darker. Likable characters die. The Musketeers themselves commit an act of extrajudicial brutality that, while true to Dumas’s novel, would probably be altered if the film were made today. From being a naive bumpkin in The Three Musketeers, The Four Musketeers finds d’Artgnan transformed into a battle weary soldier.

The cast is fabulous. This is a case of the all-star label living up to the hype. Oliver Reed, Frank Finlay, and Richard Chamberlain all seems as if they’ve been riding and fighting together for decades. Christopher Lee plays Rochefort as being an almost honorable villain while Faye Dunaway is a cunning and sexy Milady. What truly makes the film work, though, is the direction of Richard Lester. Lester stay true to the spirit of Dumas while also using the material to comment on the modern world, with the constant threat of war and civil uprising mirroring the era in which the films were made. Interestingly enough, Richard Lester first became interested in the material when Ilya Salkind reached out to the Beatles to try to convince them to play the Musketeers. While the Beatles were ultimately more interested in a never-produced adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, Richard Lester was happy to bring Dumas’s characters to life.

Both The Three Musketeers and The Four Musketeers are currently on Tubi, for anyone looking for a truly great adventure epic.

Today is Angelina Jolie’s 50th birthday.

As I sit here writing this, Jolie is very much a respectable figure, one who doesn’t appear in as many movies she once did. When she does act, it’s almost always in the type of big and rather glossy films that inevitably seem to be destined to be described as potential Oscar contenders. She’s so identified with the work that she does for UNHCR that it can be argued that she’s even better known now as a human rights activist than as an actor. (On Wikipedia, her career is listed as being “actress, director, humanitarian.”) Angelina Jolie has made the move from acting to directing and even though none of her directorial efforts have been especially memorable, they still tend to get a lot of attention because she’s Angelina Jolie. Angelina Jolie is definitely a part of the establishment and, let me make this very clear, there’s nothing wrong with that! She’s still a good actress. She seems to be far more sincere about her activism than many of her fellow Hollywood performers. Personally, I think the efforts to get her to run for political office have been a little over-the-top (and they seem to have died down after an attempted presidential draft in 2016) but again, she’s earned her success and she deserves it.

That said, it can sometimes be surprising to remember that, before she became so acceptable, Angelina Jolie was Hollywood’s wild child, the estranged daughter of Jon Voight who talked openly about being bisexual, using drugs, struggling with her mental health, and playing with knives in bed. This was the Jolie who, long before she married Brad Pitt, was married to Billy Bob Thornton and used to carry around a vial of his blood. This was the Angelia Jolie who had tattoos at a time when that actually meant something and who went out of her way to let everyone know that she was a badass who wasn’t going to let anyone push her around. This was the Angelina Jolie who was dangerous and unpredictable and who wore her wild reputation like an empowering badge of honor.

That’s the Angelina Jolie who starred in Gia.

Made for HBO in 1998, Gia was a biopic in which Jolie played Gia Carangi, one of the first supermodels. The film followed Gia, from her unhappy childhood (represented by Mercedes Ruehl as Gia’s mother) to her early modeling days when she was represented by the famous Wilhelmina Cooper (Faye Dunaway) to her struggles with heroin and cocaine to her eventual AIDS-related death. During the course of her short life, Gia falls in love with a photographer’s assistant named Linda (Elizabeth Mitchell) but, as much as Linda tries to help her, Gia simply cannot escape her demons.

That Gia is a fairly conventional biopic is not a shock, considering that it was directed by the reliably banal Michael Cristofer. He starts the film with people talking about their memories of Gia and he doesn’t get anymore imaginative from there. That the film works and is memorable is almost totally due to performances of Elizabeth Mitchell and Angelina Jolie, both of whom give such sincere and honest performances that they make you truly care about Gia and Linda. Jolie, in particular, portrays Gia as being an uninhibited and impulsive agent of chaos, one who follows her immediate desires and who makes no apology for who she is and what she does. There’s a lot of physical nudity in this film but the important thing is that Jolie allows Gia’s soul to be naked as well. There’s nothing hidden when it comes either the character or Jolie’s empathetic and passionate performance.

Jolie won an Emmy for her performance in Gia and her work in this film led to her being cast in 2000’s Girl, Interrupted, the film for which she would win the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress. Since then, Jolie’s become, as I said at the start of this review, very much a member of America’s cultural establishment. My hope, though, is that someday, someone will give Jolie a role that will remind viewers of who she was before she became respectable. I think she still has the talent to take audiences by surprise.

1971’s Hogan’s Goat opens in Brooklyn in the 1890s. This was when Brooklyn itself was still a separate city, before it become a borough of the unified New York City. If you’ve watched the video that I include with most of my Welcome Back Kotter reviews, you’ll notice the boast: “Fourth largest city” on the Welcome to Brooklyn sign. And indeed, if Brookyln had remained independent, it would now be the fourth most populated city in America, behind New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago. Sorry, Brooklyn.

(However, Houston thanks you.)

Local ward boss Matt Stanton (Robert Foxworth) heads home with what he thinks is exciting news. He tells his wife, Kathleen (Faye Dunaway), that he is finally going to be mayor of Brooklyn. The current mayor, a man named Quinn (George Rose), has been caught up in some sort of corruption and the Democratic political machine is ready to abandon him. Matt Stanton is about to become one of the most powerful men in New York. That’s not bad for a relatively young man who came to America from Ireland in search of a better life. Adding to Stanton’s happiness is the fact that he’ll be defeating Quinn, a canny politician towards whom Stanton holds a grudge. Kathleen, however, is worried. An immigrant herself, Kathleen met Stanton while the latter was in London. They were married in a civil ceremony and, ever since Stanton brought her back to Brooklyn, she has been lying and telling everyone that they were married in a church. Kathleen feels that she and Stanton have been living in sin and she wants to have a convalidation ceremony. Stanton refuses because doing so would mean admitting the lie in the first place and he can’t afford to lose the support of the Irish Catholic voters of Brooklyn.

However, it turns out that there are even more secrets in Stanton’s past, ones that Kathleen doesn’t know about but Quinn does. When those secrets start to come out, Kathleen comes to realize that there’s much that she doesn’t know about her husband. Stanton, with political power in his grasp, desperately tries to hold on to the image that he’s created of himself and Kathleen, leading to tragedy.

Hogan’s Goat was an Off-Broadway hit when it premiered in the mid-60s and its success led to Faye Dunaway getting her first film offers. The made-for-television version of Hogan’s Goat, which premiered on PBS and featured Dunaway recreating her stage role, is essentially a filmed play. Little effort was made to “open up” the story and, as a result, the film is undeniably stagy. It’s clear from the start the film was mostly shot to record Faye Dunaway’s acclaimed performance for posterity. Indeed, she’s the only member of the theatrical cast to appear in the film version. Dunaway does give a strong performance, easily dominating the film with her mix of nervous intensity and cool intelligence. The rest of the cast is a mixed bag. Robert Foxworth is appropriately driven and ambitious as Stanton but his Irish accent comes and goes. Philip Bosco does well as a sympathetic priest and George Rose is appropriately manipulative as Quinn.

In the end, the story of Hogan’s Goat is probably of the greatest interest to Irish-American history nerds like me, who have read and studied how Irish immigrants, especially in the 19th century, faced tremendous prejudice when coming to the United States and how they reacted by building their own political machines and dispensing their own patronage. In Hogan’s Goat, the conflict is less between more Stanton and Quinn and more between Kathleen’s traditional views and her devout Catholicism and Stanton’s own very American ambition. Whereas Kathleen still fights to retain her faith, pride, and her commitment to who she was before she married Stanton, Stanton fights for power and to conquer the man who Stanton feels has everything that he desires. In the end, Stanton’s hubris is not only his downfall but Kathleen’s as well.

Today is Faye Dunaway’s birthday and today’s song of the day is The Happening, which was the theme song of Dunaway’s first movie, 1966’s The Happening! Faye played a hippie who, with George Maharis and Michael Parks, kidnapped Anthony Quinn. The film wasn’t a hit but the song was.

Here are The Supremes with The Happening.

Hey, life, look at me

I can see the reality

‘Cause when you shook me, took me out of my world

I woke up

Suddenly I just woke up to the happening

When you find that you left the future behind

‘Cause when you got a tender love

You don’t take care of

Then you better beware of the happening

One day you’re up, then you turn around

You find your world is tumbling down

It happened to me, and it can happen to you

I was sure, I felt secure

Until love took a detour

Yeah, riding high on top of the world

It happened, suddenly it just happened

I saw my dreams fall apart

When love walked away from my heart

And when you lose that precious love you need

To guide you

Something happens inside you, the happening

Now I see life for what it is

It’s not all dreams, ooh, it’s not all bliss

It happened to me and it can happen to you

Once

Ooh, and then it happened

Ooh, and then it happened

Ooh, and then it happened

Ooh, and then it happened

Is it real, is it fake

Is this game of life a mistake?

‘Cause when I lost the love I thought was mine

For certain, suddenly I started hurting

I saw the light too late

When that fickle finger of fate

Yeah, came and broke my pretty balloon

I woke up

Suddenly I just woke up to the happening

So sure, I felt secure

Until love took a detour

‘Cause when you got a tender love you don’t

Take care of, then you better beware of

Songwriters: Alex Mungo / David Taylor / Jasper John Nielson Stainthorpe / Mark Robert Tiplady / Rob Downes / Stephen Wren

In 1939, an ocean liner named the MS St. Louis set sail from Hamburg. Along with the crew, the ship carried 937 passengers, all of whom were Jewish and leaving Germany to escape Nazi persecution. The ship was meant to go to Havana, where the passengers had been told that they would be given asylum. Many were hoping to reunite with family members who had already taken the voyage.

What neither the passengers nor Captain Gustav Schroeder knew was that the entire voyage was merely a propaganda operation. No sooner had the St. Louis left Hamburg than German agents and Nazi sympathizers started to rile up anti-Semitic feelings in Cuba. The plan was to prevent the passengers from disembarking in Cuba and to force the St. Louis to then return to Germany. The Nazis would be able to claim that they had given the Jews a chance to leave but that the rest of the world would not take them in. Not only would the Jews be cast as pariahs but the Germans would be able to use the world’s actions as a way to defend their own crimes.

Captain Schroeder, however, refused to play along. After he was refused permission to dock in Cuba, he then attempted to take the ship to both America and Canada. When both of those countries refused to allow him to dock, Schroeder turned the St. Louis toward England, where he planned to stage a shipwreck so that the passengers could be rescued at sea. Before that happened, Belgium, France, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom jointly announced that they would accept the refugees.

Tragically, just a few days after the passengers disembarked, World War II officially began and Belgium, France, and the Netherlands all fell to the Nazi war machine. It is estimated that, of the 937 passengers on the St. Louis, more than 600 of them subsequently died in the Nazi concentration camps.

The journey of the St. Louis was recreated in the 1976 film, Voyage of the Damned, with Max von Sydow as Captain Schroeder and a collection of familiar faces playing not only the ship’s passengers and crew but also the men and women in Cuba who all played a role in the fate of the ship. In fact, one could argue that there’s a few too many familiar faces in Voyage of the Damned. One cannot fault the performances of Max von Sydow, Malcolm McDowell, and Helmut Griem as members of the crew. And, amongst the passengers, Lee Grant, Jonathan Pryce, Paul Koslo, Sam Wanamaker, and Julie Harris all make a good impression. Even the glamorous Faye Dunaway doesn’t seem to be too out-of-place on the ship. But then, in Havana, actors like Orson Welles and James Mason are awkwardly cast as Cubans and the fact that they are very obviously not Cuban serves to take the viewer out of the story. It reminds the viewer that, as heart-breaking as the story of the St. Louis may be, they’re still just watching a movie.

That said, Voyage of the Damned still tells an important true story, one that deserves to be better-known. In its best moments, the film captures the helplessness of having nowhere to go. With Cuba corrupt and the rest of the world more interested in maintaining the illusion of peace than seriously confronting what was happening in Germany, the Jewish passengers of the St. Louis truly find themselves as a people without a home. They also discover that they cannot depend on leaders the other nations of the world to defend them.

Defending the passengers falls to a few people who are willing to defy the leaders of their own country. At the start of the film, Nazi Intelligence Chief Wilhelm Canaris (Denholm Elliott) explains that Captain Schroeder was selected specifically because he wasn’t a member of the Nazi Party and could not be accused of having ulterior motives for ultimately returning the passengers to Germany. Canaris and his fellow Nazis assume that anti-Semitism is so natural that even a non-Nazi will not care what happens to the Jewish passengers. Instead, Schroeder and his crew take it upon themselves to save the lives of the passengers. It is not Franklin Roosevelt who tries to save the passengers of St. Louis. Instead, it’s just a handful of people who, despite unrelenting pressure to do otherwise, step up to do the right thing. Max von Sydow, who was so often cast in villainous roles, gives a strong performance as the captain who is willing to sacrifice his ship to save his passengers.

Flaws and all, Voyage of the Damned is a powerful film about a moment in history that must never be forgotten.

Today is Faye Dunaway’s birthday and today’s scene that I love comes from the film that made Dunaway a star, 1967’s Bonnie and Clyde.

In this scene, Bonnie Parker (Faye Dunaway) first meets Clyde Barrow (Warren Beatty). Interestingly enough, Warren Beatty originally wanted Bob Dylan to play the role of Clyde and, at one point, he envisioned Bonnie being played by his sister, Shirley MacClaine. That would have been interesting, to say the least. Fortunately, in the end, Beatty decided to not only produce the film but to play the role of Clyde himself. Natalie Wood, Tuesday Weld, Leslie Caron, and Jane Fonda were among those who turned down the role of Bonnie before Faye Dunaway, who had done two films at that point, was eventually cast in the role. And the rest is film history!

Today, the Shattered Lens wishes a happy 81st birthday to the one and only Faye Dunaway. In honor of this day, I want to share a scene that I love from 1967’s Bonnie and Clyde.

Now, Bonnie and Clyde was not Dunaway’s first film. After appearing on Broadway, she was cast as a hippie kidnapped in a forgettable crime comedy called The Happening. Otto Preminger, who could always spot talent even if he didn’t always seem to understand how to persuade that talent to work with him, put her under contract and featured her as the wife of John Phillip Law in his legendary flop, Hurry Sundown. (Dunaway later said she had wanted to play the role of Michael Caine’s wife, a part that went to Jane Fonda and she never quite forgave Preminger for giving her a less interesting role.) Dunaway reportedly did not get along with Preminger and didn’t care much for the films that he was planning on featuring her in. One can imagine that she was happy when Warner Bros. bought her contract so that she could star opposite Warren Beatty in Bonnie and Clyde.

Despite the fact that the real-life Bonnie Parker was notably shorter and certainly nowhere as glamorous as as the actress who was selected to play, Faye Dunaway proved to be the perfect choice for the role. Bonnie and Clyde proved to be a surprise hit and an Oscar contender. It made Dunaway a star, a fashion icon, and it resulted in her first Oscar nomination. Dunaway would go on to appear in such classic 70s films as Chinatown, The Towering Inferno, Three Days of the Concord, and Network before her unfortunate decision to star as Joan Crawford in Mommie Dearest would slow the momentum of her career. Unfortunately, she would later become better known for having a difficult reputation and for engaging in some very public feuds, with the press often acting as if Dunaway was somehow uniquely eccentric in this regard. (To Hollywood, Dunaway’s sin wasn’t that she fought as much as it was that she fought in public.) Though Dunaway’s career has had its ups and downs, one cannot deny that when she was good, she was very, very good.

In this scene, from Bonnie and Clyde, Bonnie Parker (played by Faye Dunaway) writes a poem and tries to craft the future image of Bonnie and Clyde. Though it has none of the violence that made Bonnie and Clyde such a controversial film in 1967, this is still an important scene. (Actually, it’s more than one scene.) Indeed, this scene is a turning point for the entire film, the moment that Bonnie and Clyde goes from being an occasionally comedic attack on the establishment to a fatalistic crime noir. This is where Bonnie shows that, unlike Clyde, she knows that death is inescapable but she also knows that she and Clyde are destined to be legends.

(Of course, Dunaway and Beatty — two performers who one epitomized an era but only work occasionally nowadays — are already legends.)

The 1967 film, The Happening, opens with two “young” people — Sureshot (Michael Parks) and Sandy (Faye Dunaway) — waking up on a Florida beach. The previous night, they attended a party so wild that the beach is full of passed out people, one of whom apparently fell asleep while standing on his head. (It’s a happening!) From the dialogue, we discover that, despite their impeccably clean-cut appearances, both Sureshot and Sandy are meant to be hippies.

After trying to remember whether or not they “made love” the previous night (wow, how edgy!), Sandy and Sureshot attempt to find their way off of the beach. As they walk along, they’re joined by two other partygoers. Taurus is played by George Maharis, who was 38 when this film was shot and looked about ten years older. Taurus is a tough guy who carries a gun and dreams of being a revolutionary and who says stuff like, “Bam! Et cetera!” Herbie is eccentric, thin, and neurotic and, presumably because Roddy McDowall wanted too much money, he’s played by Robert Walker, Jr.

Anyway, the four of them end up stealing a boat and talking about how life is a drag, man. Eventually, they end up breaking into a mansion and threatening the owner and his wife. Since this movie was made before the Manson murders, this is all played for laughs. The owner of the mansion is Roc Delmonico (Anthony Quinn). Roc used to be a gangster but now he’s a legitimate businessman. The “hippies” decide to kidnap Roc because they assume they’ll be able to get a lot of money for him.

The only problem is that no one is willing to pay the ransom!

Not Roc’s wife (Martha Hyer)!

Not Roc’s best friend (Milton Berle), who happens to be sleeping with Roc’s wife!

Not Roc’s former mob boss (Oscar Homolka)!

Roc gets so angry when he find out that no one wants to pay that he decides to take control of the kidnapping, He announces that he knows secrets about everyone who refused to pay any money for him and unless they do pay the ransom, he’s going to reveal them. We’ve gone from kidnapping to blackmail.

Along the way, Roc bonds with his kidnappers. He teaches them how to commit crimes and they teach him how to be anti-establishment or something. Actually, I’m not sure what they were supposed to have taught him. The Happening is a comedy that I guess was trying to say something about the divide between the young and the middle-aged but it doesn’t really have much of a message beyond that the middle-aged could stand to laugh a little more and that the young are just silly and kind of useless. Of course, the whole young/old divide would probably work better if all of the young hippies weren’t played by actors who were all either in their 30 or close enough to 30 to make their dorm room angst seem a bit silly.

It’s an odd film. The tone is all over the place and everyone seems to be acting in a different movie. Anthony Quinn actually gives a pretty good dramatic performance but his good performance only serves to highlight how miscast almost everyone else in the film is. Michael Parks comes across like he would rather be beating up hippies than hanging out with them while Faye Dunaway seems to be bored with the entire film. George Maharis, meanwhile, goes overboard on the Brando impersonation while Robert Walker, Jr. seems like he just needs someone to tell him to calm down.

But even beyond the weird mix of acting style, the film’s message is a mess. On the one hand, the “hippies” are presented as being right about the establishment being full of hypocritical phonies. On the other hand, the establishment is proven to be correct about the “hippies” being a bunch of easily distracted idiots. This is one of those films that wants to have it both ways, kind of like an old episode of Saved By The Bell where Mr. Belding learns to loosen up while Zack learns to respect authority. This is an offer that you can refuse.

And that’s what’s happening!

Previous Offers You Can’t (or Can) Refuse: